Exam Questions: Types, Characteristics, and Suggestions

Examinations are a very common assessment and evaluation tool in universities and there are many types of examination questions. This tips sheet contains a brief description of seven types of examination questions, as well as tips for using each of them: 1) multiple choice, 2) true/false, 3) matching, 4) short answer, 5) essay, 6) oral, and 7) computational. Remember that some exams can be conducted effectively in a secure online environment in a proctored computer lab or assigned as paper based or online “take home” exams.

Multiple choice

Multiple choice questions are composed of one question (stem) with multiple possible answers (choices), including the correct answer and several incorrect answers (distractors). Typically, students select the correct answer by circling the associated number or letter, or filling in the associated circle on the machine-readable response sheet.

Example : Distractors are:

A) Elements of the exam layout that distract attention from the questions B) Incorrect but plausible choices used in multiple choice questions C) Unnecessary clauses included in the stem of multiple choice questions Answer: B

Students can generally respond to these type of questions quite quickly. As a result, they are often used to test student’s knowledge of a broad range of content. Creating these questions can be time consuming because it is often difficult to generate several plausible distractors. However, they can be marked very quickly.

Tips for writing good multiple choice items:

Suggestion : After each lecture during the term, jot down two or three multiple choice questions based on the material for that lecture. Regularly taking a few minutes to compose questions, while the material is fresh in your mind, will allow you to develop a question bank that you can use to construct tests and exams quickly and easily.

True/false questions are only composed of a statement. Students respond to the questions by indicating whether the statement is true or false. For example: True/false questions have only two possible answers (Answer: True).

Like multiple choice questions, true/false questions:

- Are most often used to assess familiarity with course content and to check for popular misconceptions

- Allow students to respond quickly so exams can use a large number of them to test knowledge of a broad range of content

- Are easy and quick to grade but time consuming to create

True/false questions provide students with a 50% chance of guessing the right answer. For this reason, multiple choice questions are often used instead of true/false questions.

Tips for writing good true/false items:

Suggestion : You can increase the usefulness of true/false questions by asking students to correct false statements.

Students respond to matching questions by pairing each of a set of stems (e.g., definitions) with one of the choices provided on the exam. These questions are often used to assess recognition and recall and so are most often used in courses where acquisition of detailed knowledge is an important goal. They are generally quick and easy to create and mark, but students require more time to respond to these questions than a similar number of multiple choice or true/false items.

Example: Match each question type with one attribute:

- Multiple Choice a) Only two possible answers

- True/False b) Equal number of stems and choices

- Matching c) Only one correct answer but at least three choices

Tips for writing good matching items:

Suggestion: You can use some choices more than once in the same matching exercise. It reduces the effects of guessing.

Short answer

Short answer questions are typically composed of a brief prompt that demands a written answer that varies in length from one or two words to a few sentences. They are most often used to test basic knowledge of key facts and terms. An example this kind of short answer question follows:

“What do you call an exam format in which students must uniquely associate a set of prompts with a set of options?” Answer: Matching questions

Alternatively, this could be written as a fill-in-the-blank short answer question:

“An exam question in which students must uniquely associate prompts and options is called a ___________ question.” Answer: Matching.

Short answer questions can also be used to test higher thinking skills, including analysis or evaluation. For example:

“Will you include short answer questions on your next exam? Please justify your decision with two to three sentences explaining the factors that have influenced your decision.”

Short answer questions have many advantages. Many instructors report that they are relatively easy to construct and can be constructed faster than multiple choice questions. Unlike matching, true/false, and multiple choice questions, short answer questions make it difficult for students to guess the answer. Short answer questions provide students with more flexibility to explain their understanding and demonstrate creativity than they would have with multiple choice questions; this also means that scoring is relatively laborious and can be quite subjective. Short answer questions provide more structure than essay questions and thus are often easy and faster to mark and often test a broader range of the course content than full essay questions.

Tips for writing good short answer items:

Suggestion : When using short answer questions to test student knowledge of definitions consider having a mix of questions, some that supply the term and require the students to provide the definition, and other questions that supply the definition and require that students provide the term. The latter sort of questions can be structured as fill-in-the-blank questions. This mix of formats will better test student knowledge because it doesn’t rely solely on recognition or recall of the term.

Essay questions provide a complex prompt that requires written responses, which can vary in length from a couple of paragraphs to many pages. Like short answer questions, they provide students with an opportunity to explain their understanding and demonstrate creativity, but make it hard for students to arrive at an acceptable answer by bluffing. They can be constructed reasonably quickly and easily but marking these questions can be time-consuming and grader agreement can be difficult.

Essay questions differ from short answer questions in that the essay questions are less structured. This openness allows students to demonstrate that they can integrate the course material in creative ways. As a result, essays are a favoured approach to test higher levels of cognition including analysis, synthesis and evaluation. However, the requirement that the students provide most of the structure increases the amount of work required to respond effectively. Students often take longer to compose a five paragraph essay than they would take to compose five one paragraph answers to short answer questions. This increased workload limits the number of essay questions that can be posed on a single exam and thus can restrict the overall scope of an exam to a few topics or areas. To ensure that this doesn’t cause students to panic or blank out, consider giving the option of answering one of two or more questions.

Tips for writing good essay items:

Suggestions : Distribute possible essay questions before the exam and make your marking criteria slightly stricter. This gives all students an equal chance to prepare and should improve the quality of the answers – and the quality of learning – without making the exam any easier.

Oral examinations allow students to respond directly to the instructor’s questions and/or to present prepared statements. These exams are especially popular in language courses that demand ‘speaking’ but they can be used to assess understanding in almost any course by following the guidelines for the composition of short answer questions. Some of the principle advantages to oral exams are that they provide nearly immediate feedback and so allow the student to learn as they are tested. There are two main drawbacks to oral exams: the amount of time required and the problem of record-keeping. Oral exams typically take at least ten to fifteen minutes per student, even for a midterm exam. As a result, they are rarely used for large classes. Furthermore, unlike written exams, oral exams don’t automatically generate a written record. To ensure that students have access to written feedback, it is recommended that instructors take notes during oral exams using a rubric and/or checklist and provide a photocopy of the notes to the students.

In many departments, oral exams are rare. Students may have difficulty adapting to this new style of assessment. In this situation, consider making the oral exam optional. While it can take more time to prepare two tests, having both options allows students to choose the one which suits them and their learning style best.

Computational

Computational questions require that students perform calculations in order to solve for an answer. Computational questions can be used to assess student’s memory of solution techniques and their ability to apply those techniques to solve both questions they have attempted before and questions that stretch their abilities by requiring that they combine and use solution techniques in novel ways.

Effective computational questions should:

- Be solvable using knowledge of the key concepts and techniques from the course. Before the exam solve them yourself or get a teaching assistant to attempt the questions.

- Indicate the mark breakdown to reinforce the expectations developed in in-class examples for the amount of detail, etc. required for the solution.

To prepare students to do computational questions on exams, make sure to describe and model in class the correct format for the calculations and answer including:

- How students should report their assumptions and justify their choices

- The units and degree of precision expected in the answer

Suggestion : Have students divide their answer sheets into two columns: calculations in one, and a list of assumptions, description of process and justification of choices in the other. This ensures that the marker can distinguish between a simple mathematical mistake and a profound conceptual error and give feedback accordingly.

If you would like support applying these tips to your own teaching, CTE staff members are here to help. View the CTE Support page to find the most relevant staff member to contact.

- Cunningham, G.K. (1998). Assessment in the Classroom. Bristol, PA: Falmer Press.

- Ward, A.W., & Murray-Ward, M. (1999). Assessment in the Classroom. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Co.

This Creative Commons license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon our work non-commercially, as long as they credit us and indicate if changes were made. Use this citation format: Exam questions: types, characteristics and suggestions . Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo .

Catalog search

Teaching tip categories.

- Assessment and feedback

- Blended Learning and Educational Technologies

- Career Development

- Course Design

- Course Implementation

- Inclusive Teaching and Learning

- Learning activities

- Support for Student Learning

- Support for TAs

- Assessment and Feedback

Five Common Types of Essay Exam Questions and What They Mean

PDF Download

Prompts are words that explain how you should structure your response to an essay exam question. These explanations serve as general guidelines. Depending on your course, there may be exceptions to what these prompts mean.

1. Explain

State your opinion and describe your thought process. Clarify the meaning of these words within the context of your course.

Discuss

Consider various points of view; carefully analyze and give reasons to support your ideas.

Analyze

Summarize in detail and with a clear focus; consider parts of ideas and their relationships. In some contexts, analysis may involve evaluation.

Explain

Clarify, interpret, or give reasons for differences in opinion or results; analyze causes.

Illustrate

Use words, pictures, diagrams, or concrete examples to clarify a point.

Outline

Organize a description based on main and subordinate points, stress the arrangement and classification of the subject.

Describe the evolution, development, or progress of the subject in a narrative form.

Respond to the question and defend a judgment on the issue, idea, or question involved. The underlying questions to answer include “to what extent?” and “how well?”

Criticize

Judge the truth or usefulness of the views or factors mentioned in the question.

Give your views, mention limitations and advantages; include the opinion of authorities and give evidence to support your position.

Interpret

Translate, give examples, or comment on a subject; include your own viewpoint.

Review

Critically examine a subject; analyze and comment upon it or statements made about it.

Analyze at least two different ideas in terms of their similarities and differences. You may also discuss the connections between these ideas.

Compare

Look for qualities that resemble each other, emphasize similarities, but also note differences.

Show how ideas or concepts are connected to each other.

Contrast

Stress the differences of ideas, concepts, events, and problems; also note similarities.

Take a position and defend your argument against reasonable alternatives.

Prove

Establish the truth of a statement by using evidence and logical reasoning.

Justify

Show strong reasons for decisions or conclusions; use convincing arguments based on evidence.

5. Identify

Give a direct answer. You may not be required to provide further explanation. These questions are not usually seen on essay exams. However, when they do appear, you are still expected to explain and elaborate upon your ideas.

Write a series of concise statements.

Write in a list or outline; make concise points one by one.

Describe

Recount, characterize, sketch, relate in a sequence or story.

Give clear, concise, authoritative meanings.

State

Present main points in brief clear sequence; usually omit the minor details and examples.

Give the main points or facts in condensed form; omit details and illustrations.

Give a graphic answer, drawing, chart, plan, or schematic representation.

Back to the top

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Types of Exams

Anita Frederiks; Kate Derrington; and Cristy Bartlett

Introduction

There are many different types of exams and exam questions that you may need to prepare for at university. Each type of exam has different considerations and preparation, in addition to knowing the course material. This chapter extends the discussion from the previous chapter and examines different types of exams, including multiple choice, essay, and maths exams, and some strategies specific for those exam types. The aim of this chapter is to provide you with an overview of the different types of exams and the specific strategies for preparing and undertaking them.

The COVID19 pandemic has led to a number of activities previously undertaken on campus becoming online activities. This includes exams, so we have provided advice for both on campus (or in person) exams as well as alternative and online exams. We recommend that you read the chapter Preparing for Exams before reading this chapter about the specific types of exams that you will be undertaking.

Types of exams

During your university studies you may have exams that require you to attend in person, either on campus or at a study centre, or you may have online exams. Regardless of whether you take the exam in person or online, your exams may have different requirements and it is important that you know what those requirements are. We have provided an overview of closed, restricted, and open exams below, but always check the specific requirements for your exams.

Closed exams

These exams allow you to bring only your writing and drawing instruments. Formula sheets (in the case of maths and statistics exams) may or may not be provided.

Restricted exams

These exams allow you to bring in only specific things such as a single page of notes, or in the case of maths exams, a calculator or a formula sheet. You may be required to hand in your notes or formula sheet with your exam paper.

Open book exams

These exams allow you to have access to any printed or written material and a calculator (if required) during the exam. If you are completing your exam online, you may also be able to access online resources. The emphasis in open book exams is on conceptual understanding and application of knowledge rather than just the ability to recall facts.

Myth: You may think open book exams will be easier than closed exams because you can have all your study materials with you.

Reality: Open book exams require preparation, a good understanding of your content and an effective system of organising your notes so you can find the relevant information quickly during your exam. Open book exams generally require more detailed responses. You are required to demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of a subject as well as your ability to find and apply information applicable to the topic. Questions in open book exams often require complex answers and you are expected to use reason and evidence to support your responses. The more organised you are, the more time you have to focus on answering your questions and less time on searching for information in your notes and books. Consider these tips in the table below when preparing for an open book exam.

Tips for preparing your materials for open or unrestricted exams

- Organise your notes logically with headings and page numbers

- Use different colours to highlight and separate different topics

- Be familiar with the layout of any books you will be using during the exam. Use sticky notes to mark important information for quick reference during the exam.

- Use your learning objectives from each week or for each new module of content, to help determine what is important (and likely to be on the exam).

- Create an alphabetical index for all the important topics likely to be on the exam. Include the page numbers, in your notes or textbooks, of where to find the relevant information on these topics.

- If you have a large quantity of other documents, for example if you are a law student, consider binding legislation and cases or place them in a folder. Use sticky notes to indicate the most relevant sections.

- Write a summary page which includes, where relevant, important definitions, formulas, rules, graphs and diagrams with examples if required.

- Know how to use your calculator efficiently and effectively (if required).

Take home exams

These are a special type of open book exam where you are provided with the exam paper and are able to complete it away from an exam centre over a set period of time. You are able to use whatever books, journals, websites you have available and as a result, take-home exams usually require more exploration and in-depth responses than other types of exams.

It is just as important to be organised with take home exams. Although there is usually a longer period available for completing these types of exams, the risk is that you can spend too long researching and not enough time planning and writing your exam. It is also important to allow enough time for submitting your completed exam.

Tips for completing take home exams

- Arrange for a quiet and organised space to do the exam

- Tell your family or house mates that you will be doing a take-home exam and that you would appreciate their cooperation

- Make sure you know the correct date of submission for the exam paper

- Know the exam format, question types and content that will be covered

- As with open book exams, read your textbook and work through any chapter questions

- Do preliminary research and bookmark useful websites or download relevant journal articles

- Take notes and/or mark sections of your textbook with sticky notes

- Organise and classify your notes in a logical order so once you know the exam topic you will be able to find what you need to answer it easily

When answering open book and take-home exams remember these three steps below.

Multiple choice

Multiple choice questions are often used in online assignments, quizzes, and exams. It is tempting to think that these types of questions are easier than short answer or essay questions because the answer is right in front of you. However, like other types of assessment, multiple choice questions require you to understand and apply the content from your study materials or lectures. This requires preparation and thorough content knowledge to be able to retrieve the correct answer quickly. The following sections discuss strategies on effectively preparing for, and answering, multiple choice questions, the typical format of multiple choice questions, and some common myths about these types of questions.

Preparing for multiple choice questions

- Prepare as you do for other types of exams (see the Preparing for Exams chapter for study strategies).

- Find past or practice exam papers (where available), and practise doing multiple choice questions.

- Create your own multiple choice questions to assess the content, this prompts you to think about the material more deeply and is a good way to practise answering multiple choice questions.

- If there are quizzes in your course, complete these (you may be able to have multiple attempts to help build your skills).

- Calculate the time allowed for answering the multiple-choice section of the exam. Ideally do this before you get to the exam if you know the details.

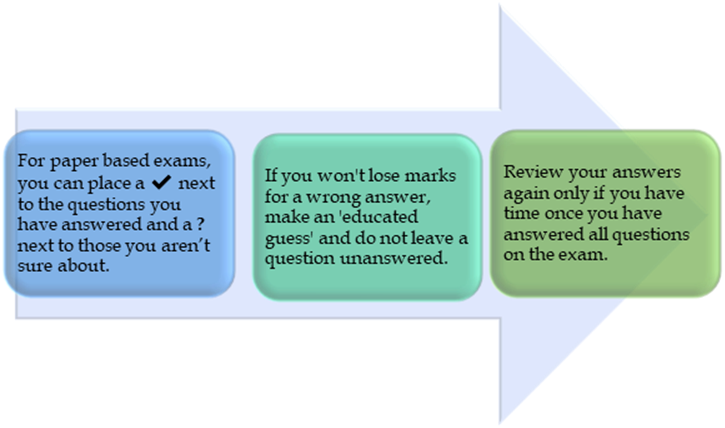

Strategies for use during the exam

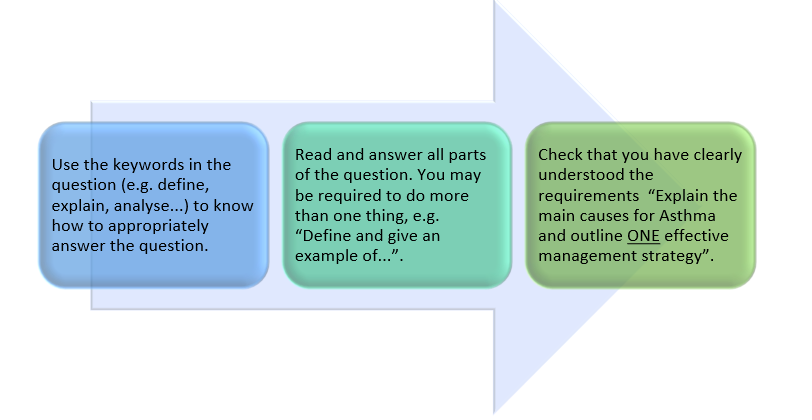

- Consider the time allocated per question to guide how you use your time in the exam. Don’t spend all of your time on one question, leaving the rest unanswered. Figure 23.3 provides some strategies for managing questions during the exam.

- Carefully mark your response to the questions and ensure that your answer matches the question number on the answer sheet.

- Review your answers if you have time once you have answered all questions on the exam.

Format of multiple choice questions

The most frequently used format of a multiple choice question has two components, the question (may include additional detail or statement) and possible answers.

Table 23.1 Multiple choice questions

The example below is of a simple form of multiple choice question.

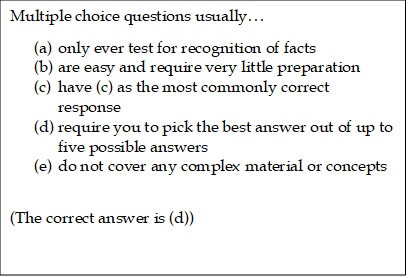

Multiple choice myths

These are some of the common myths about multiple choice questions that are NOT accurate:

- You don’t need to study for multiple choice tests

- Multiple choice questions are easy to get right

- Getting these questions correct is just good luck

- Multiple choice questions take very little time to read and answer

- Multiple choice questions cannot cover complex concepts or ideas

- C is most likely correct

- Answers will always follow a pattern, e.g., badcbadcbadc

- You get more questions correct if you alternate your answers

None of the answers above are correct! Multiple choice questions may appear short with the answer provided, but this does not mean that you will be able to complete them quickly. Some questions require thought and further calculations before you can determine the answer.

Short answer exams

Short answer, or extended response exams focus on knowledge and understanding of terms and concepts along with the relationships between them. Depending on your study area, short answer responses could require you to write a sentence or a short paragraph or to solve a mathematical problem. Check the expectations with your lecturer or tutor prior to your exam. Try the preparation strategies suggested in the section below.

Preparation strategies for short answer responses

- Concentrate on key terms and concepts

- It is not advised to prepare and learn specific answers as you may not get that exact question on exam day; instead know how to apply your content.

- Learn similarities and differences between similar terms and concepts, e.g. stalagmite and stalactite.

- Learn some relevant examples or supporting evidence you can apply to demonstrate your application and understanding.

There are also some common mistakes to avoid when completing your short answer exam as seen below.

Common mistakes in short answer responses

- Misinterpreting the question

- Not answering the question sufficiently

- Not providing an example

- Response not structured or focused

- Wasting time on questions worth fewer marks

- Leaving questions unanswered

- Not showing working (if calculations were required)

Use these three tips in Figure 23.6 when completing your short answer responses.

Essay exams

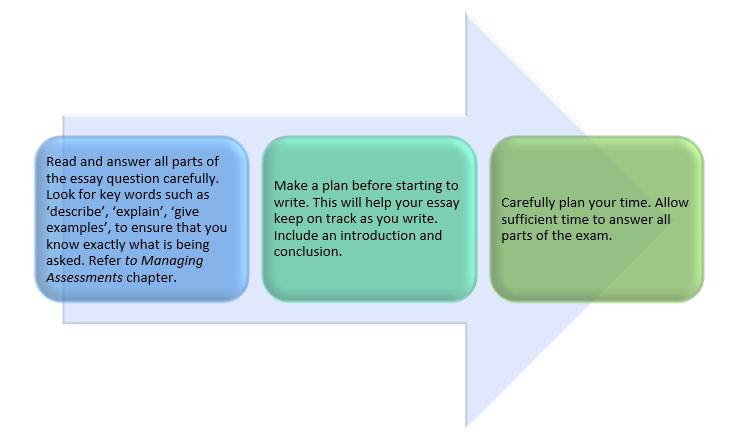

As with other types of exams, you should adjust your preparation to suit the style of questions you will be asked. Essay exam questions require a response with multiple paragraphs and should be logical and well-structured.

It is preferable not to prepare and learn an essay in anticipation of the question you may get on the exam. Instead, it is better to learn the information that you would need to include in an essay and be able to apply this to the specific question on exam day. Although you may have an idea of the content that will be examined, usually you will not know the exact question. If your exam is handwritten, ensure that your writing is legible. You won’t get any marks if your writing cannot be read by your marker. You may wish to practise your handwriting, so you are less fatigued in the exam.

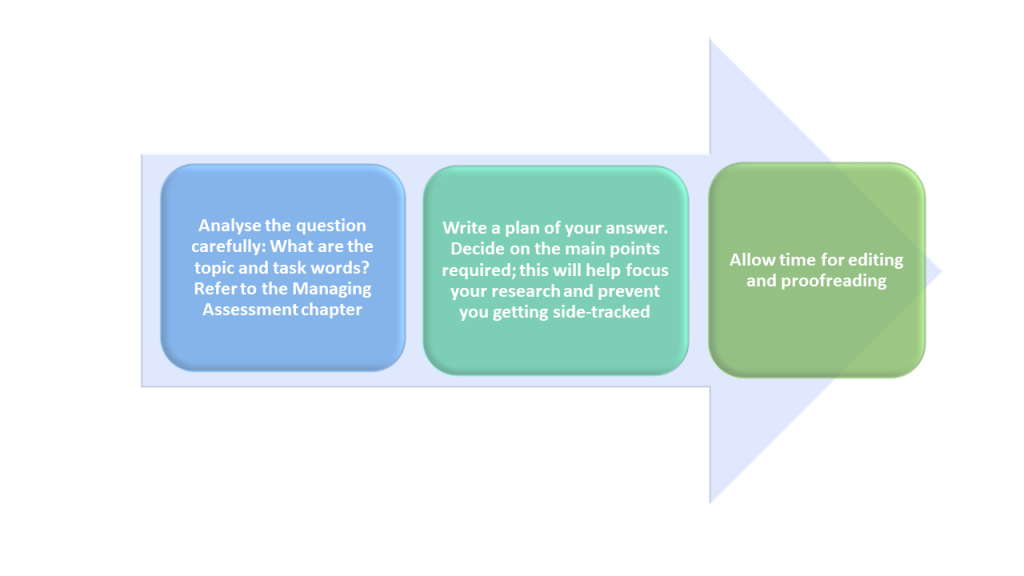

Follow these three tips in Figure 23.7 below for completing an essay exam.

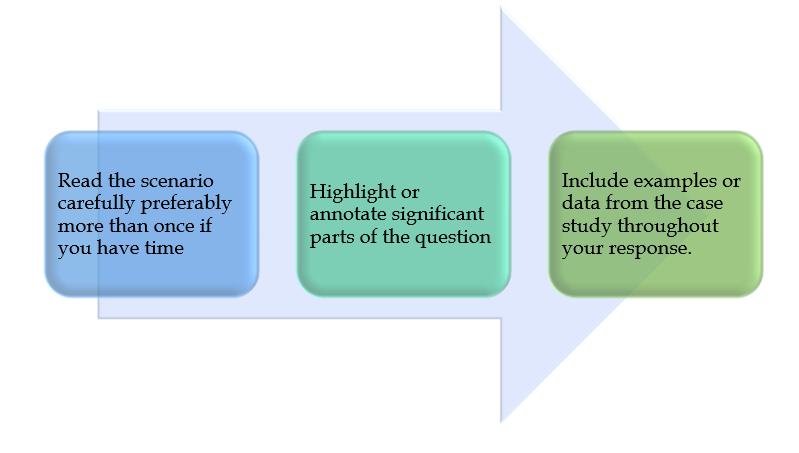

Case study exams

Case study questions in exams are often quite complex and include multiple details. This is deliberate to allow you to demonstrate your problem solving and critical thinking abilities. Case study exams require you to apply your knowledge to a real-life situation. The exam question may include information in various formats including a scenario, client brief, case history, patient information, a graph, or table. You may be required to answer a series of questions or interpret or conduct an analysis. Follow the tips below in Figure 23.8 for completing a case study response.

Maths exams

This section covers strategies for preparing and completing, maths-based exams. When preparing for a maths exam, an important consideration is the type of exam you will be sitting and what you can, and cannot, bring in with you (for in person exams). Maths exams may be open, restricted or closed. More information about each of these is included in Table 23.2 below. The information about the type of exam for your course can be found in the examination information provided by your university.

Table 23.2 Types of maths exams

Once you have considered the type of exam you will be taking and know what materials you will be able to use, you need to focus on preparing for the exam. Preparation for your maths exams should be happening throughout the semester.

Maths exam preparation tips

- Review the information about spaced practice in the previous chapter Preparing for Exams to maximise your exam preparation

- It is best NOT to start studying the night before the exam. Cramming doesn’t work as well as spending regular time studying throughout the course. See additional information on cramming in the previous chapter Preparing for Exams ).

- Review your notes and make a concise list of important concepts and formulae

- Make sure you know these formulae and more importantly, how to use them

- Work through your tutorial problems again (without looking at the solutions). Do not just read over them. Working through problems will help you to remember how to do them.

- Work through any practice or past exams which have been provided to you. You can also make your own practice exam by finding problems from your course materials. See the Practice Testing section in the previous Preparing for Exams chapter for more information.

- When working through practice exams, give yourself a time limit. Don’t use your notes or books, treat it like the real exam.

- Finally, it is essential to get a good night’s sleep before the exam so you are well rested and can concentrate when you take the exam.

Multiple choice questions in maths exams

Multiple choice questions in maths exams normally test your knowledge of concepts and may require you to complete calculations. For more information about answering multiple choice questions, please see the multiple choice exam section in this chapter.

Short answer questions in maths exams

These type of questions in a maths exam require you to write a short answer response to the question and provide any mathematical working. Things to remember for these question types include:

- what the question is asking you to do?

- what information are you given?

- is there anything else you need to do (multi-step questions) to get the answer?

- Highlight/underline the key words. If possible, draw a picture—this helps to visualise the problem (and there may be marks associated with diagrams).

- Show all working! Markers cannot give you makes if they cannot follow your working.

- Check your work.

- Ensure that your work is clear and able to be read.

Exam day tips

Before you start your maths exam, you should take some time to peruse (read through) the exam. Regardless of whether your exam has a dedicated perusal time, we recommend that you spend time at the beginning of the exam to read through the whole exam. Below are some strategies for perusing and completing maths based exams.

When you commence your exam:

- Read the exam instructions carefully, if you have any queries, clarify with your exam supervisor

- During the perusal time, write down anything you are worried about forgetting during the exam

- Read each question carefully, look for key words, make notes and write formulae

- Prioritise questions. Do the questions you are most comfortable with first and spend more time on the questions worth more marks. This will help you to maximise your marks.

Once you have read through your options and made a plan on how to best approach your exam, it is time to focus on completing your maths exam. During your exam:

- Label each question clearly—this will allow the marker to find each question (and part), as normally you can answer questions in any order you want! (If you are required to answer the questions in a particular order it will be included as part of your exam instructions.)

- If you get stuck, write down anything you know about that type of question – it could earn you marks

- The process is important—show that you understand the process by writing your working or the process, even if the numbers don’t work out

- If you get really stuck on a question, don’t spend too long on it. Complete the other questions, something might come to you when you are working on a different question.

- Where possible, draw pictures even if you can’t find the words to explain

- Avoid using whiteout to correct mistakes, use a single line to cross out incorrect working

- Don’t forget to use the correct units of measurement

- If time permits, check your working and review your work once you have answered all the questions

This chapter provided an overview of different types of exams and some specific preparation strategies. Practising for the specific type of exam you will be completing has a number of benefits, including helping you to become comfortable (or at least familiar) with the type of exam and allowing you to focus on answering the questions themselves. It also allows you to adapt your exam preparation to best prepare you for the exam.

- Know your exam type and practise answering those types of questions.

- Ensure you know the requirements for your specific type of exam (e.g., closed, restricted, open book) and what materials you can use in the exam.

- Multiple choice exams – read the response options carefully.

- Short answer exams– double check that you have answered all parts of the question.

- Essay exams – practise writing essay responses under timed exam conditions.

- Case study exams – ensure that you refer to the case in your response.

- Maths exams – include your working for maths and statistics exams

- For handwritten exams write legibly, so your maker can read your work.

Academic Success Copyright © 2021 by University of Southern Queensland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Essay Exams

What this handout is about.

At some time in your undergraduate career, you’re going to have to write an essay exam. This thought can inspire a fair amount of fear: we struggle enough with essays when they aren’t timed events based on unknown questions. The goal of this handout is to give you some easy and effective strategies that will help you take control of the situation and do your best.

Why do instructors give essay exams?

Essay exams are a useful tool for finding out if you can sort through a large body of information, figure out what is important, and explain why it is important. Essay exams challenge you to come up with key course ideas and put them in your own words and to use the interpretive or analytical skills you’ve practiced in the course. Instructors want to see whether:

- You understand concepts that provide the basis for the course

- You can use those concepts to interpret specific materials

- You can make connections, see relationships, draw comparisons and contrasts

- You can synthesize diverse information in support of an original assertion

- You can justify your own evaluations based on appropriate criteria

- You can argue your own opinions with convincing evidence

- You can think critically and analytically about a subject

What essay questions require

Exam questions can reach pretty far into the course materials, so you cannot hope to do well on them if you do not keep up with the readings and assignments from the beginning of the course. The most successful essay exam takers are prepared for anything reasonable, and they probably have some intelligent guesses about the content of the exam before they take it. How can you be a prepared exam taker? Try some of the following suggestions during the semester:

- Do the reading as the syllabus dictates; keeping up with the reading while the related concepts are being discussed in class saves you double the effort later.

- Go to lectures (and put away your phone, the newspaper, and that crossword puzzle!).

- Take careful notes that you’ll understand months later. If this is not your strong suit or the conventions for a particular discipline are different from what you are used to, ask your TA or the Learning Center for advice.

- Participate in your discussion sections; this will help you absorb the material better so you don’t have to study as hard.

- Organize small study groups with classmates to explore and review course materials throughout the semester. Others will catch things you might miss even when paying attention. This is not cheating. As long as what you write on the essay is your own work, formulating ideas and sharing notes is okay. In fact, it is a big part of the learning process.

- As an exam approaches, find out what you can about the form it will take. This will help you forecast the questions that will be on the exam, and prepare for them.

These suggestions will save you lots of time and misery later. Remember that you can’t cram weeks of information into a single day or night of study. So why put yourself in that position?

Now let’s focus on studying for the exam. You’ll notice the following suggestions are all based on organizing your study materials into manageable chunks of related material. If you have a plan of attack, you’ll feel more confident and your answers will be more clear. Here are some tips:

- Don’t just memorize aimlessly; clarify the important issues of the course and use these issues to focus your understanding of specific facts and particular readings.

- Try to organize and prioritize the information into a thematic pattern. Look at what you’ve studied and find a way to put things into related groups. Find the fundamental ideas that have been emphasized throughout the course and organize your notes into broad categories. Think about how different categories relate to each other.

- Find out what you don’t know, but need to know, by making up test questions and trying to answer them. Studying in groups helps as well.

Taking the exam

Read the exam carefully.

- If you are given the entire exam at once and can determine your approach on your own, read the entire exam before you get started.

- Look at how many points each part earns you, and find hints for how long your answers should be.

- Figure out how much time you have and how best to use it. Write down the actual clock time that you expect to take in each section, and stick to it. This will help you avoid spending all your time on only one section. One strategy is to divide the available time according to percentage worth of the question. You don’t want to spend half of your time on something that is only worth one tenth of the total points.

- As you read, make tentative choices of the questions you will answer (if you have a choice). Don’t just answer the first essay question you encounter. Instead, read through all of the options. Jot down really brief ideas for each question before deciding.

- Remember that the easiest-looking question is not always as easy as it looks. Focus your attention on questions for which you can explain your answer most thoroughly, rather than settle on questions where you know the answer but can’t say why.

Analyze the questions

- Decide what you are being asked to do. If you skim the question to find the main “topic” and then rush to grasp any related ideas you can recall, you may become flustered, lose concentration, and even go blank. Try looking closely at what the question is directing you to do, and try to understand the sort of writing that will be required.

- Focus on what you do know about the question, not on what you don’t.

- Look at the active verbs in the assignment—they tell you what you should be doing. We’ve included some of these below, with some suggestions on what they might mean. (For help with this sort of detective work, see the Writing Center handout titled Reading Assignments.)

Information words, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject. Information words may include:

- define—give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning.

- explain why/how—give reasons why or examples of how something happened.

- illustrate—give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject.

- summarize—briefly cover the important ideas you learned about the subject.

- trace—outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form.

- research—gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you’ve found.

Relation words ask you to demonstrate how things are connected. Relation words may include:

- compare—show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different).

- contrast—show how two or more things are dissimilar.

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation.

- cause—show how one event or series of events made something else happen.

- relate—show or describe the connections between things.

Interpretation words ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Don’t see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation. Interpretation words may include:

- prove, justify—give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth.

- evaluate, respond, assess—state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons (you may want to compare your subject to something else).

- support—give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe).

- synthesize—put two or more things together that haven’t been put together before; don’t just summarize one and then the other, and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together (as opposed to compare and contrast—see above).

- analyze—look closely at the components of something to figure out how it works, what it might mean, or why it is important.

- argue—take a side and defend it (with proof) against the other side.

Plan your answers

Think about your time again. How much planning time you should take depends on how much time you have for each question and how many points each question is worth. Here are some general guidelines:

- For short-answer definitions and identifications, just take a few seconds. Skip over any you don’t recognize fairly quickly, and come back to them when another question jogs your memory.

- For answers that require a paragraph or two, jot down several important ideas or specific examples that help to focus your thoughts.

- For longer answers, you will need to develop a much more definite strategy of organization. You only have time for one draft, so allow a reasonable amount of time—as much as a quarter of the time you’ve allotted for the question—for making notes, determining a thesis, and developing an outline.

- For questions with several parts (different requests or directions, a sequence of questions), make a list of the parts so that you do not miss or minimize one part. One way to be sure you answer them all is to number them in the question and in your outline.

- You may have to try two or three outlines or clusters before you hit on a workable plan. But be realistic—you want a plan you can develop within the limited time allotted for your answer. Your outline will have to be selective—not everything you know, but what you know that you can state clearly and keep to the point in the time available.

Again, focus on what you do know about the question, not on what you don’t.

Writing your answers

As with planning, your strategy for writing depends on the length of your answer:

- For short identifications and definitions, it is usually best to start with a general identifying statement and then move on to describe specific applications or explanations. Two sentences will almost always suffice, but make sure they are complete sentences. Find out whether the instructor wants definition alone, or definition and significance. Why is the identification term or object important?

- For longer answers, begin by stating your forecasting statement or thesis clearly and explicitly. Strive for focus, simplicity, and clarity. In stating your point and developing your answers, you may want to use important course vocabulary words from the question. For example, if the question is, “How does wisteria function as a representation of memory in Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom?” you may want to use the words wisteria, representation, memory, and Faulkner) in your thesis statement and answer. Use these important words or concepts throughout the answer.

- If you have devised a promising outline for your answer, then you will be able to forecast your overall plan and its subpoints in your opening sentence. Forecasting impresses readers and has the very practical advantage of making your answer easier to read. Also, if you don’t finish writing, it tells your reader what you would have said if you had finished (and may get you partial points).

- You might want to use briefer paragraphs than you ordinarily do and signal clear relations between paragraphs with transition phrases or sentences.

- As you move ahead with the writing, you may think of new subpoints or ideas to include in the essay. Stop briefly to make a note of these on your original outline. If they are most appropriately inserted in a section you’ve already written, write them neatly in the margin, at the top of the page, or on the last page, with arrows or marks to alert the reader to where they fit in your answer. Be as neat and clear as possible.

- Don’t pad your answer with irrelevancies and repetitions just to fill up space. Within the time available, write a comprehensive, specific answer.

- Watch the clock carefully to ensure that you do not spend too much time on one answer. You must be realistic about the time constraints of an essay exam. If you write one dazzling answer on an exam with three equally-weighted required questions, you earn only 33 points—not enough to pass at most colleges. This may seem unfair, but keep in mind that instructors plan exams to be reasonably comprehensive. They want you to write about the course materials in two or three or more ways, not just one way. Hint: if you finish a half-hour essay in 10 minutes, you may need to develop some of your ideas more fully.

- If you run out of time when you are writing an answer, jot down the remaining main ideas from your outline, just to show that you know the material and with more time could have continued your exposition.

- Double-space to leave room for additions, and strike through errors or changes with one straight line (avoid erasing or scribbling over). Keep things as clean as possible. You never know what will earn you partial credit.

- Write legibly and proofread. Remember that your instructor will likely be reading a large pile of exams. The more difficult they are to read, the more exasperated the instructor might become. Your instructor also cannot give you credit for what they cannot understand. A few minutes of careful proofreading can improve your grade.

Perhaps the most important thing to keep in mind in writing essay exams is that you have a limited amount of time and space in which to get across the knowledge you have acquired and your ability to use it. Essay exams are not the place to be subtle or vague. It’s okay to have an obvious structure, even the five-paragraph essay format you may have been taught in high school. Introduce your main idea, have several paragraphs of support—each with a single point defended by specific examples, and conclude with a restatement of your main point and its significance.

Some physiological tips

Just think—we expect athletes to practice constantly and use everything in their abilities and situations in order to achieve success. Yet, somehow many students are convinced that one day’s worth of studying, no sleep, and some well-placed compliments (“Gee, Dr. So-and-so, I really enjoyed your last lecture”) are good preparation for a test. Essay exams are like any other testing situation in life: you’ll do best if you are prepared for what is expected of you, have practiced doing it before, and have arrived in the best shape to do it. You may not want to believe this, but it’s true: a good night’s sleep and a relaxed mind and body can do as much or more for you as any last-minute cram session. Colleges abound with tales of woe about students who slept through exams because they stayed up all night, wrote an essay on the wrong topic, forgot everything they studied, or freaked out in the exam and hyperventilated. If you are rested, breathing normally, and have brought along some healthy, energy-boosting snacks that you can eat or drink quietly, you are in a much better position to do a good job on the test. You aren’t going to write a good essay on something you figured out at 4 a.m. that morning. If you prepare yourself well throughout the semester, you don’t risk your whole grade on an overloaded, undernourished brain.

If for some reason you get yourself into this situation, take a minute every once in a while during the test to breathe deeply, stretch, and clear your brain. You need to be especially aware of the likelihood of errors, so check your essays thoroughly before you hand them in to make sure they answer the right questions and don’t have big oversights or mistakes (like saying “Hitler” when you really mean “Churchill”).

If you tend to go blank during exams, try studying in the same classroom in which the test will be given. Some research suggests that people attach ideas to their surroundings, so it might jog your memory to see the same things you were looking at while you studied.

Try good luck charms. Bring in something you associate with success or the support of your loved ones, and use it as a psychological boost.

Take all of the time you’ve been allotted. Reread, rework, and rethink your answers if you have extra time at the end, rather than giving up and handing the exam in the minute you’ve written your last sentence. Use every advantage you are given.

Remember that instructors do not want to see you trip up—they want to see you do well. With this in mind, try to relax and just do the best you can. The more you panic, the more mistakes you are liable to make. Put the test in perspective: will you die from a poor performance? Will you lose all of your friends? Will your entire future be destroyed? Remember: it’s just a test.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Axelrod, Rise B., and Charles R. Cooper. 2016. The St. Martin’s Guide to Writing , 11th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Fowler, Ramsay H., and Jane E. Aaron. 2016. The Little, Brown Handbook , 13th ed. Boston: Pearson.

Gefvert, Constance J. 1988. The Confident Writer: A Norton Handbook , 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

Kirszner, Laurie G. 1988. Writing: A College Rhetoric , 2nd ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Woodman, Leonara, and Thomas P. Adler. 1988. The Writer’s Choices , 2nd ed. Northbrook, Illinois: Scott Foresman.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Writing Center

Essay exams, select and analyze your question, manage your time, brainstorming and organizing, editing and proofreading, also recommended for you:.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

When approaching any essay exam, it is important to identify what kind of response is expected—that is, what is being asked of you and what information you are required to include. This handout outlines several question types and includes key words to look for when deciding how to respond to an essay prompt.

This tips sheet contains a brief description of seven types of examination questions, as well as tips for using each of them: 1) multiple choice, 2) true/false, 3) matching, 4) short answer, 5) essay, 6) oral, and 7) computational.

State your opinion and describe your thought process. Clarify the meaning of these words within the context of your course. Consider various points of view; carefully analyze and give reasons to support your ideas. Summarize in detail and with a clear focus; consider parts of ideas and their relationships.

This chapter extends the discussion from the previous chapter and examines different types of exams, including multiple choice, essay, and maths exams, and some strategies specific for those exam types.

Essay exams are a useful tool for finding out if you can sort through a large body of information, figure out what is important, and explain why it is important. Essay exams challenge you to come up with key course ideas and put them in your own words and to use the interpretive or analytical skills you’ve practiced in the course.

To support educators, this workbook is divided into sections answering the following three questions: 1. What is an essay question? 2. When should essay questions be used? 3. How should essay questions be constructed? The format of this workbook is suitable for use with seminars or workshops and can be. facilitated by an instructor.

This handout discusses how to write a timed essay exam in a class. The first step is to study the material. It might also help to ask your instructor if you can see sample essay exams from a past class to get an idea of the level of detail he or she prefers.