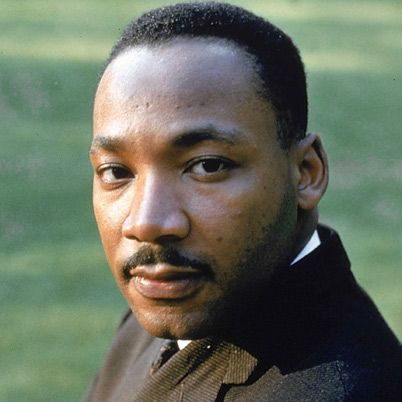

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. was a Baptist minister and major leader of the Civil Rights Movement. After his assassination, he was memorialized by Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

In Focus: Martin Luther King Jr. Day

This year’s Martin Luther King Jr. Day, on January 15, coincides with the late civil rights leader ’s birthday. Had he lived, King would be turning 95 years old.

Days after his 1968 assassination , a campaign for a holiday in King’s honor began. U.S. Representative John Conyers Jr. of Michigan first proposed a bill on April 8, 1968, but the first vote on the legislation didn’t happen until 1979. King’s widow, Coretta Scott King , led the lobbying effort to drum up public support. Fifteen years after its introduction, the bill finally became law.

In 1983, President Ronald Reagan ’s signature created Martin Luther King Jr. Day of Service as a federal holiday. It’s celebrated annually on the third Monday in January. The only national day of service, Martin Luther King Jr. Day was first celebrated in 1986. The first time all 50 states recognized the holiday was in 2000.

See Martin Luther King Jr.’s life depicted onscreen in the 2018 documentary I Am MLK Jr. or the Oscar-winning movie Selma .

Who Was Martin Luther King Jr?

Quick facts, where did martin luther king jr. go to school, philosophy of nonviolence, civil rights accomplishments, "i have a dream" and other famous speeches, wife and kids, fbi surveillance, later activism, assassination.

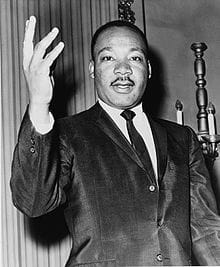

Martin Luther King Jr. was a Baptist minister and civil rights activist who had a seismic impact on race relations in the United States, beginning in the mid-1950s. Among his many efforts, King headed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Through his nonviolent activism and inspirational speeches , he played a pivotal role in ending legal segregation of Black Americans, as well as the creation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 . King won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, among several other honors. He was assassinated by James Earl Ray and died on April 4, 1968, at age 39. King continues to be remembered as one of the most influential and inspirational Black leaders in history.

FULL NAME: Martin Luther King Jr. BIRTHDAY: January 15, 1929 DIED: April 4, 1968 BIRTHPLACE: Atlanta, Georgia SPOUSE: Coretta Scott King (1953-1968) CHILDREN: Yolanda, Martin III, Dexter, and Bernice King ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Capricorn

Martin Luther King Jr. was born as Michael Luther King Jr. in Atlanta. His birthday was January 15, 1929.

His parents were Michael Luther King Sr. and Alberta Williams King. The Williams and King families had roots in rural Georgia. Martin’s maternal grandfather, A.D. Williams, was a rural minister for years and then moved to Atlanta in 1893. He took over the small, struggling Ebenezer Baptist Church with around 13 members and made it into a forceful congregation. He married Jennie Celeste Parks, and they had one child who survived, Alberta.

Michael Sr. came from a family of sharecroppers in a poor farming community. He married Alberta in 1926 after an eight-year courtship. The newlyweds moved to A.D.’s home in Atlanta. Michael stepped in as pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church upon the death of his father-in-law in 1931. He, too, became a successful minister and adopted the name Martin Luther King Sr. in honor of the German Protestant religious leader Martin Luther . In due time, Michael Jr. followed his father’s lead and adopt the name himself to become Martin Luther King Jr.

A middle child, Martin Jr. had an older sister, Willie, and a younger brother, Alfred. The King children grew up in a secure and loving environment. Martin Sr. was more the disciplinarian, while Alberta’s gentleness easily balanced out their father’s strict hand.

Although they undoubtedly tried, Martin Jr.’s parents couldn’t shield him completely from racism. His father fought against racial prejudice, not just because his race suffered, but also because he considered racism and segregation to be an affront to God’s will. He strongly discouraged any sense of class superiority in his children, which left a lasting impression on Martin Jr.

Growing up in Atlanta, King entered public school at age 5. In May 1936, he was baptized, but the event made little impression on him.

In May 1941, King was 12 years old when his grandmother Jennie died of a heart attack. The event was traumatic for the boy, more so because he was out watching a parade against his parents’ wishes when she died. Distraught at the news, young King jumped from a second-story window at the family home, allegedly attempting suicide.

King attended Booker T. Washington High School, where he was said to be a precocious student. He skipped both the ninth and eleventh grades and, at age 15, entered Morehouse College in Atlanta in 1944. He was a popular student, especially with his female classmates, but largely unmotivated, floating through his first two years.

Influenced by his experiences with racism, King began planting the seeds for a future as a social activist early in his time at Morehouse. “I was at the point where I was deeply interested in political matters and social ills,” he recalled in The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr . “I could envision myself playing a part in breaking down the legal barriers to Negro rights.”

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.

At the time, King felt that the best way to serve that purpose was as a lawyer or a doctor. Although his family was deeply involved in the church and worship, King questioned religion in general and felt uncomfortable with overly emotional displays of religious worship. This discomfort had continued through much of his adolescence, initially leading him to decide against entering the ministry, much to his father’s dismay.

But in his junior year, King took a Bible class, renewed his faith, and began to envision a career in the ministry. In the fall of his senior year, he told his father of his decision, and he was ordained at Ebenezer Baptist Church in February 1948.

Later that year, King earned a sociology degree from Morehouse College and began attended the liberal Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania. He thrived in all his studies, was elected student body president, and was valedictorian of his class in 1951. He also earned a fellowship for graduate study.

Even though King was following his father’s footsteps, he rebelled against Martin Sr.’s more conservative influence by drinking beer and playing pool while at college. He became romantically involved with a white woman and went through a difficult time before he could break off the relationship.

During his last year in seminary, King came under the guidance of Morehouse College President Benjamin E. Mays, who influenced King’s spiritual development. Mays was an outspoken advocate for racial equality and encouraged King to view Christianity as a potential force for social change.

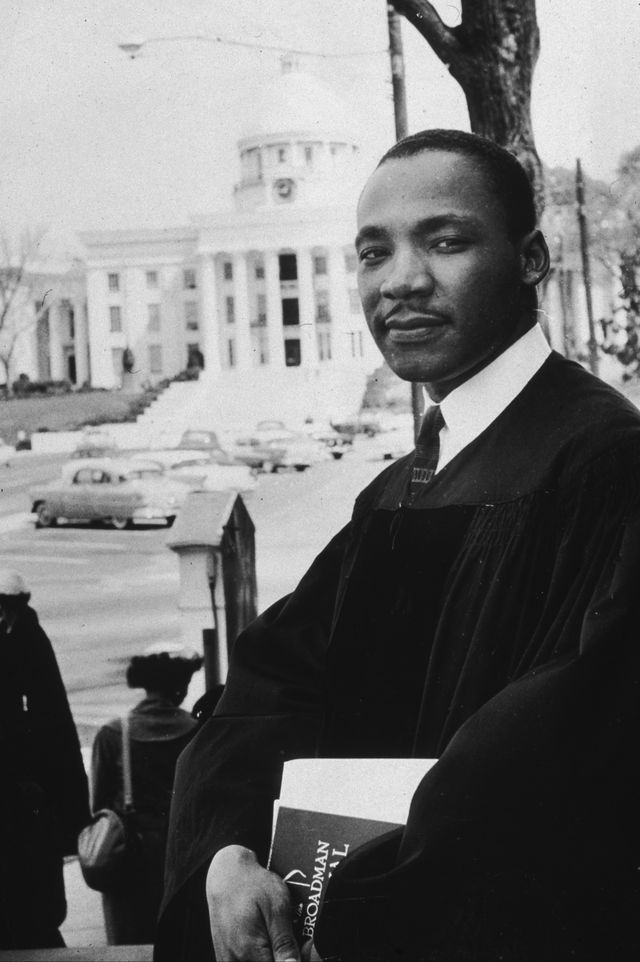

After being accepted at several colleges for his doctoral study, King enrolled at Boston University. In 1954, while still working on his dissertation, King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church of Montgomery, Alabama. He completed his doctorate and earned his degree in 1955 at age 25.

Decades after King’s death, in the late 1980s, researchers at Stanford University’s King Papers Project began to note similarities between passages of King’s doctoral dissertation and those of another student’s work. A committee of scholars appointed by Boston University determined that King was guilty of plagiarism in 1991, though it also recommended against the revocation of his degree.

First exposed to the concept of nonviolent resistance while reading Henry David Thoreau ’s On Civil Disobedience at Morehouse, King later discovered a powerful exemplar of the method’s possibilities through his research into the life of Mahatma Gandhi . Fellow civil rights activist Bayard Rustin , who had also studied Gandhi’s teachings, became one of King’s associates in the 1950s and counseled him to dedicate himself to the principles of nonviolence.

As explained in his autobiography , King previously felt that the peaceful teachings of Jesus applied mainly to individual relationships, not large-scale confrontations. But he came to realize: “Love for Gandhi was a potent instrument for social and collective transformation. It was in this Gandhian emphasis on love and nonviolence that I discovered the method for social reform that I had been seeking.”

It led to the formation of King’s six principles of nonviolence :

- Nonviolence is a way of life for courageous people.

- Nonviolence seeks to win friendship and understanding.

- Nonviolence seeks to defeat injustice, not people.

- Nonviolence holds that suffering for a just cause can educate and transform.

- Nonviolence chooses love instead of hate.

- Nonviolence believes that the universe is on the side of justice.

In the years to come, King also frequently cited the “ Beloved Community ”—a world in which a shared spirit of compassion brings an end to the evils of racism, poverty, inequality, and violence—as the end goal of his activist efforts.

Led by his religious convictions and philosophy of nonviolence, King became one of the most prominent figures of the Civil Rights Movement . He was a founding member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and played key roles in several major demonstrations that transformed society. This included the Montgomery Bus Boycott that integrated Alabama’s public transit, the Greensboro Sit-In movement that desegregated lunch counters across the South, the March on Washington that led to the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and the Selma-to-Montgomery marches in Alabama that culminated in the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

King’s efforts earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 when he was 35.

Montgomery Bus Boycott

King’s first leadership role within the Civil Rights Movement was during the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955–1956. The 381-day protest integrated the Alabama city’s public transit in one of the largest and most successful mass movements against racial segregation in history.

The effort began on December 1, 1955, when 42-year-old Rosa Parks boarded the Cleveland Avenue bus to go home after an exhausting day at work. She sat in the first row of the “colored” section in the middle of the bus. As the bus traveled its route, all the seats in the white section filled up, then several more white passengers boarded the bus.

The bus driver noted that there were several white men standing and demanded that Parks and several other African Americans give up their seats. Three other Black passengers reluctantly gave up their places, but Parks remained seated.

The driver asked her again to give up her seat, and again she refused. Parks was arrested and booked for violating the Montgomery City Code. At her trial a week later, in a 30-minute hearing, Parks was found guilty and fined $10 and assessed $4 court fee.

The local NAACP chapter had been looking to challenge Montgomery’s segregated bus policy and had almost made 15-year-old Claudette Colvin the face of the campaign months earlier. She similarly refused to give up her bus seat to a white man on March 2, 1955, but after organizers learned Colvin was pregnant, they feared it would scandalize the deeply religious Black community and make Colvin, along with the group’s efforts, less credible in the eyes of sympathetic white people. Parks’ experience of discrimination provided another opportunity.

On the night Parks was arrested, E.D. Nixon , head of the local NAACP chapter, met with King and other local civil rights leaders to plan a Montgomery Bus Boycott. King was elected to lead the boycott because he was young, well-trained, and had solid family connections and professional standing. He was also new to the community and had few enemies, so organizers felt he would have strong credibility with the Black community.

In his first speech as the group’s president, King declared:

“We have no alternative but to protest. For many years, we have shown an amazing patience. We have sometimes given our white brothers the feeling that we liked the way we were being treated. But we come here tonight to be saved from that patience that makes us patient with anything less than freedom and justice.”

King’s skillful rhetoric put new energy into the civil rights struggle in Alabama. The Montgomery Bus Boycott began December 5, 1955, and for more than a year, the local Black community walked to work, coordinated ride sharing, and faced harassment, violence, and intimidation. Both King’s and Nixon’s homes were attacked.

In addition to the boycott, members of the Black community took legal action against the city ordinance that outlined the segregated transit system. They argued it was unconstitutional based on the U.S. Supreme Court ’s “separate is never equal” decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Several lower courts agreed, and the nation’s Supreme Court upheld the ruling in a November 13, 1956, decision that also ruled the state of Alabama’s bus segregation laws were unconstitutional.

After the legal defeats and large financial losses, the city of Montgomery lifted the law that mandated segregated public transportation. The boycott ended on December 20, 1956.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

Flush with victory, African American civil rights leaders recognized the need for a national organization to help coordinate their efforts. In January 1957, King, Ralph Abernathy , and 60 ministers and civil rights activists founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to harness the moral authority and organizing power of Black churches. The SCLC helped conduct nonviolent protests to promote civil rights reform.

King’s participation in the organization gave him a base of operation throughout the South, as well as a national platform. The SCLC felt the best place to start to give African Americans a voice was to enfranchise them in the voting process. In February 1958, the SCLC sponsored more than 20 mass meetings in key southern cities to register Black voters. King met with religious and civil rights leaders and lectured all over the country on race-related issues.

Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story

That September, King survived an attempt on his life when a woman with mental illness stabbed him in the chest as he signed copies of his book Stride Toward Freedom in a New York City department store. Saved by quick medical attention, King expressed sympathy for his assailant’s condition in the aftermath .

In 1959, with the help of the American Friends Service Committee, King visited Gandhi ’s birthplace in India. The trip affected him in a profound way, increasing his commitment to America’s civil rights struggle.

Greensboro Sit-In

By 1960, King was gaining national exposure. He returned to Atlanta to become co-pastor with his father at Ebenezer Baptist Church but also continued his civil rights efforts. His next activist campaign was the student-led Greensboro Sit-In movement.

In February 1960, a group of Black students in Greensboro, North Carolina , began sitting at racially segregated lunch counters in the city’s stores. When asked to leave or sit in the “colored” section, they just remained seated, subjecting themselves to verbal and sometimes physical abuse.

The movement quickly gained traction in several other cities. That April, the SCLC held a conference at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, with local sit-in leaders. King encouraged students to continue to use nonviolent methods during their protests. Out of this meeting, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) formed and, for a time, worked closely with the SCLC. By August 1960, the sit-ins had successfully ended segregation at lunch counters in 27 southern cities. But the movement wasn’t done yet.

On October 19, 1960, King and 75 students entered a local department store and requested lunch-counter service but were denied. When they refused to leave the counter area, King and 36 others were arrested. Realizing the incident would hurt the city’s reputation, Atlanta’s mayor negotiated a truce, and charges were eventually dropped.

Soon after, King was imprisoned for violating his probation on a traffic conviction. The news of his imprisonment entered the 1960 presidential campaign when candidate John F. Kennedy made a phone call to Martin’s wife, Coretta Scott King . Kennedy expressed his concern over the harsh treatment Martin received for the traffic ticket, and political pressure was quickly set in motion. King was soon released.

Letter from Birmingham Jail

In the spring of 1963, King organized a demonstration in downtown Birmingham, Alabama. With entire families in attendance, city police turned dogs and fire hoses on demonstrators. King was jailed, along with large numbers of his supporters.

The event drew nationwide attention. However, King was personally criticized by Black and white clergy alike for taking risks and endangering the children who attended the demonstration.

In his famous Letter from Birmingham Jail , King eloquently spelled out his theory of nonviolence: “Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community, which has constantly refused to negotiate, is forced to confront the issue.”

1963 March on Washington

By the end of the Birmingham campaign, King and his supporters were making plans for a massive demonstration on the nation’s capital composed of multiple organizations, all asking for peaceful change. The demonstration was the brainchild of labor leader A. Philip Randolph and King’s one-time mentor Bayard Rustin .

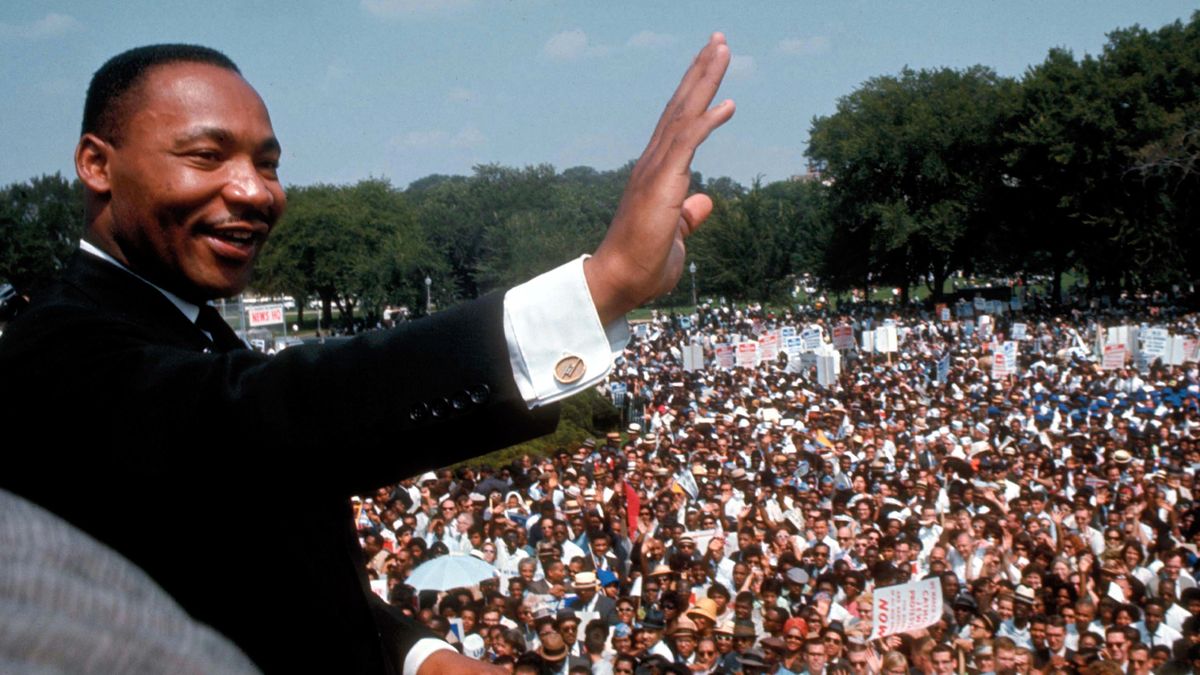

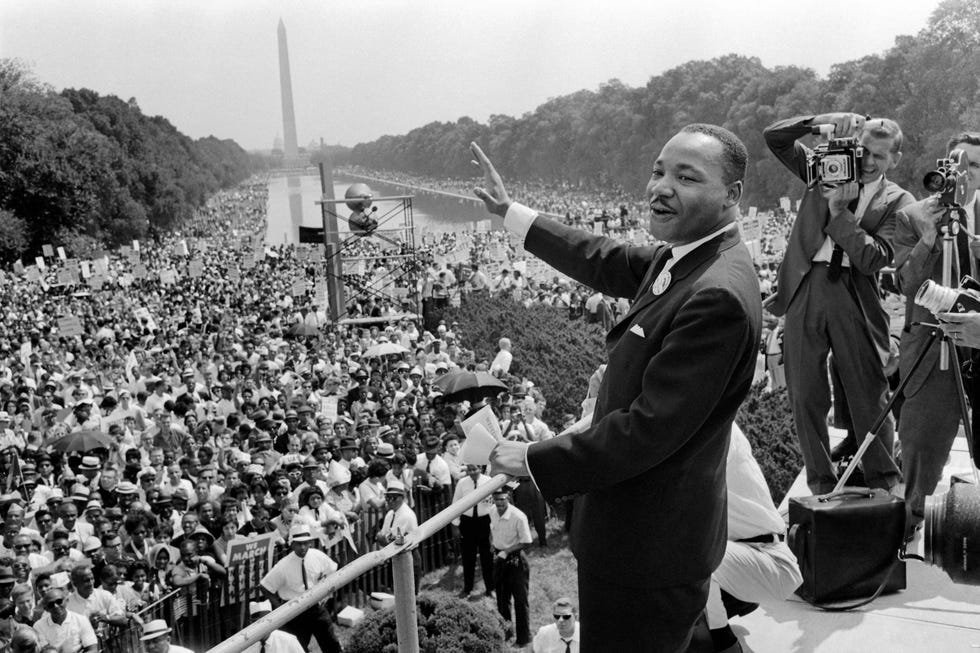

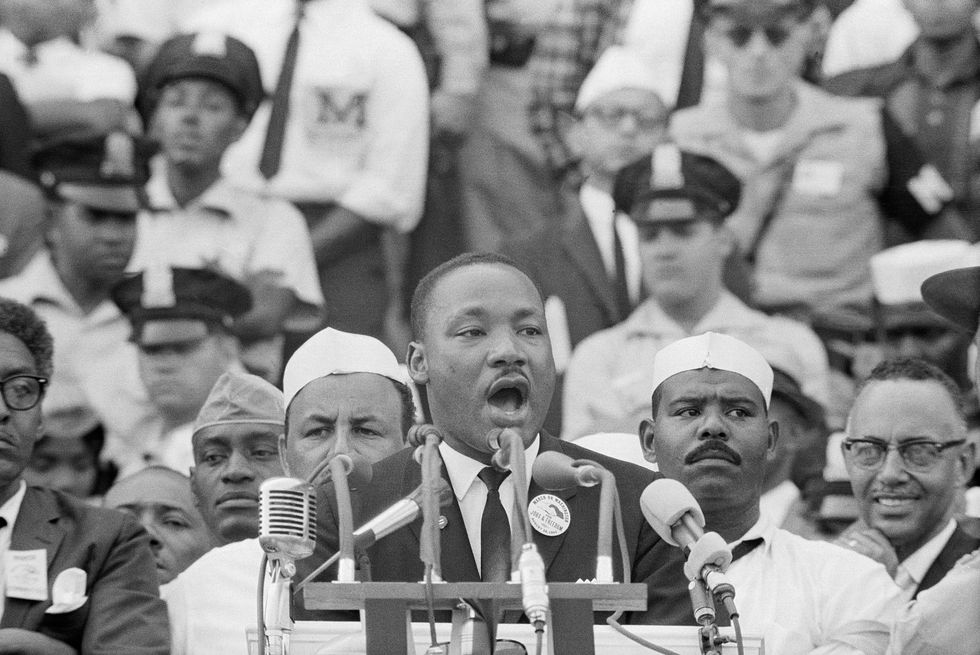

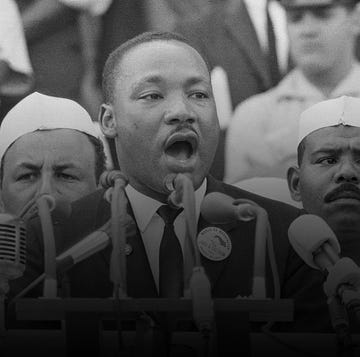

On August 28, 1963, the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom drew an estimated 250,000 people in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial. It remains one of the largest peaceful demonstrations in American history. During the demonstration, King delivered his famed “I Have a Dream” speech .

The rising tide of civil rights agitation that had culminated in the March on Washington produced a strong effect on public opinion. Many people in cities not experiencing racial tension began to question the nation’s Jim Crow laws and the near-century of second-class treatment of African American citizens since the end of slavery. This resulted in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 , authorizing the federal government to enforce desegregation of public accommodations and outlawing discrimination in publicly owned facilities.

Selma March

Continuing to focus on voting rights, King, the SCLC, SNCC, and local organizers planned to march peacefully from Selma, Alabama, to the state’s capital, Montgomery.

Led by John Lewis and Hosea Williams , demonstrators set out on March 7, 1965. But the Selma march quickly turned violent as police with nightsticks and tear gas met the demonstrators as they tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. The attack was televised, broadcasting the horrifying images of marchers being bloodied and severely injured to a wide audience. Of the 600 demonstrators, 58 were hospitalized in a day that became known as “ Bloody Sunday .” King, however, was spared because he was in Atlanta.

Not to be deterred, activists attempted the Selma-to-Montgomery march again. This time, King made sure he was part of it. Because a federal judge had issued a temporary restraining order on another march, a different approach was taken.

On March 9, 1965, a procession of 2,500 marchers, both Black and white, set out once again to cross the Pettus Bridge and confronted barricades and state troopers. Instead of forcing a confrontation, King led his followers to kneel in prayer, then they turned back. This became known as “Turnaround Tuesday.”

Alabama Governor George Wallace continued to try to prevent another march until President Lyndon B. Johnson pledged his support and ordered U.S. Army troops and the Alabama National Guard to protect the protestors.

On March 21, 1965, approximately 2,000 people began a march from Selma to Montgomery. On March 25, the number of marchers, which had grown to an estimated 25,000 gathered in front of the state capitol where King delivered a televised speech. Five months after the historic peaceful protest, President Johnson signed the 1965 Voting Rights Act .

Along with his “I Have a Dream” and “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speeches, King delivered several acclaimed addresses over the course of his life in the public eye.

“I Have A Dream” Speech

Date: august 28, 1963.

King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech during the 1963 March on Washington. Standing at the Lincoln Memorial, he emphasized his belief that someday all men could be brothers to the 250,000-strong crowd.

Notable Quote: “I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

“Give Us the Ballot” Speech

Date: may 17, 1957.

Six years before he told the world of his dream, King stood at the same Lincoln Memorial steps as the final speaker of the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom. Dismayed by the ongoing obstacles to registering Black voters, King urged leaders from various backgrounds—Republican and Democrat, Black and white—to work together in the name of justice.

Notable Quote: “Give us the ballot, and we will no longer have to worry the federal government about our basic rights. Give us the ballot, and we will no longer plead to the federal government for passage of an anti-lynching law... Give us the ballot, and we will transform the salient misdeeds of bloodthirsty mobs into the calculated good deeds of orderly citizens.”

Nobel Peace Prize Acceptance Speech

Date: december 10, 1964.

Speaking at the University of Oslo in Norway, King pondered why he was receiving the Nobel Prize when the battle for racial justice was far from over, before acknowledging that it was in recognition of the power of nonviolent resistance. He then compared the foot soldiers of the Civil Rights Movement to the ground crew at an airport who do the unheralded-yet-necessary work to keep planes running on schedule.

Notable Quote: “I think Alfred Nobel would know what I mean when I say that I accept this award in the spirit of a curator of some precious heirloom which he holds in trust for its true owners—all those to whom beauty is truth and truth, beauty—and in whose eyes the beauty of genuine brotherhood and peace is more precious than diamonds or silver or gold.”

“Our God is Marching On (How Long? Not Long)” Speech

Date: march 25, 1965.

At the end of the bitterly fought Selma-to-Montgomery march, King addressed a crowd of 25,000 supporters from the Alabama State Capitol. Offering a brief history lesson on the roots of segregation, King emphasized that there would be no stopping the effort to secure full voting rights, while suggesting a more expansive agenda to come with a call to march on poverty.

Notable Quote: “I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long, because ‘truth crushed to earth will rise again.’ How long? Not long, because ‘no lie can live forever.’... How long? Not long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

“Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence” Speech

Date: april 4, 1967.

One year before his assassination, King delivered a controversial sermon at New York City’s Riverside Church in which he condemned the Vietnam War. Explaining why his conscience had forced him to speak up, King expressed concern for the poor American soldiers pressed into conflict thousands of miles from home, while pointedly faulting the U.S. government’s role in escalating the war.

Notable Quote: “We still have a choice today: nonviolent coexistence or violent co-annihilation. We must move past indecision to action. We must find new ways to speak for peace in Vietnam and justice throughout the developing world, a world that borders on our doors. If we do not act, we shall surely be dragged down the long, dark, and shameful corridors of time reserved for those who possess power without compassion, might without morality, and strength without sight.”

“I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” Speech

Date: april 3, 1968.

The well-known orator delivered his final speech the day before he died at the Mason Temple in Memphis, Tennessee. King reflected on major moments of progress in history and his own life, in addition to encouraging the city’s striking sanitation workers.

Notable Quote: “I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the promised land.”

While working on his doctorate at Boston University, King met Coretta Scott , an aspiring singer and musician at the New England Conservatory school in Boston. They were married on June 18, 1953, and had four children—two daughters and two sons—over the next decade. Their oldest, Yolanda, was born in 1955, followed by sons Martin Luther King III in 1957 and Dexter in 1961. The couple welcomed Bernice King in 1963.

Although she accepted the responsibility to raise the children while King travelled the country, Coretta opened their home to organizational meetings and served as an advisor and sounding board for her husband. “I am convinced that if I had not had a wife with the fortitude, strength, and calmness of Corrie, I could not have withstood the ordeals and tensions surrounding the movement,” King wrote in his autobiography.

His lengthy absences became a way of life for their children, but Martin III remembered his father returning from the road to join the kids playing in the yard or bring them to the local YMCA for swimming. King also fostered discussions at mealtimes to make sure everyone understood the important issues he was seeking to resolve.

Leery of accumulating wealth as a high-profile figure, King insisted his family live off his salary as a pastor. However, he was known to splurge on good suits and fine dining, while contrasting his serious public image with a lively sense of humor among friends and family.

Due to his relationships with alleged Communists, King became a target of FBI surveillance and, from late 1963 until his death, a campaign to discredit the civil rights activist. While FBI wiretaps failed to produce evidence of Communist sympathies, they captured the civil rights leader’s engagement in extramarital dalliances. This led to the infamous “suicide letter” of 1964, later confirmed to be from the FBI and authorized by then-Director J. Edgar Hoover , which urged King to kill himself if he wanted to prevent news of his affairs from going public.

In 2019, historian David Garrow wrote of explosive new allegations against King following his review of recently released FBI documents. Among the discoveries was a memo suggesting that King had encouraged the rape of a parishioner in a hotel room, as well as evidence that he might have fathered a daughter with a mistress. Other historians questioned the veracity of the documentation, especially given the FBI’s known attempts to damage King’s reputation. The original surveillance tapes regarding these allegations are under judicial seal until 2027.

From late 1965 through 1967, King expanded his civil rights efforts into other larger American cities, including Chicago and Los Angeles. But he met with increasing criticism and public challenges from young Black power leaders. King’s patient, non-violent approach and appeal to white middle-class citizens alienated many Black militants who considered his methods too weak, too late, and ineffective.

To address this criticism, King began making a link between discrimination and poverty, and he began to speak out against the Vietnam War . He felt America’s involvement in Vietnam was politically untenable and the government’s conduct in the war was discriminatory to the poor. He sought to broaden his base by forming a multiracial coalition to address the economic and unemployment problems of all disadvantaged people. To that end, plans were in the works for another march on Washington to highlight the Poor People’s Campaign, a movement intended to pressure the government into improving living and working conditions for the economically disadvantaged.

By 1968, the years of demonstrations and confrontations were beginning to wear on King. He had grown tired of marches, going to jail, and living under the constant threat of death. He was becoming discouraged at the slow progress of civil rights in America and the increasing criticism from other African American leaders.

In the spring of 1968, a labor strike by Memphis, Tennessee, sanitation workers drew King to one last crusade. On April 3, 1968, he gave his final and what proved to be an eerily prophetic speech, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” in which he told supporters, “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now… I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

While standing on a balcony outside his room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, Martin Luther King Jr. was killed by a sniper’s bullet on April 4, 1968. King died at age 39. The shocking assassination sparked riots and demonstrations in more than 100 cities across the country.

The shooter was James Earl Ray , a malcontent drifter and former convict. He initially escaped authorities but was apprehended after a two-month international manhunt. In 1969, Ray pleaded guilty to assassinating King and was sentenced to 99 years in prison.

The identity of King’s assassin has been the source of some controversy. Ray recanted his confession shortly after he was sentenced, and King’s son Dexter publicly defended Ray’s innocence after meeting with the convicted gunman in 1997. Another complicating factor is the 1993 confession of tavern owner Loyd Jowers, who said he contracted a different hit man to kill King. In June 2000, the U.S. Justice Department released a report that dismissed the alternative theories of King’s death. Ray died in prison on April 23, 1998.

King’s life had a seismic impact on race relations in the United States. Years after his death, he is the most widely known Black leader of his era.

His life and work have been honored with a national holiday, schools and public buildings named after him, and a memorial on Independence Mall in Washington, D.C.

Over the years, extensive archival studies have led to a more balanced and comprehensive assessment of his life, portraying him as a complex figure: flawed, fallible, and limited in his control over the mass movements with which he was associated, yet a visionary leader who was deeply committed to achieving social justice through nonviolent means.

- But we come here tonight to be saved from that patience that makes us patient with anything less than freedom and justice.

- There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over and men are no longer willing to be plunged into an abyss of injustice where they experience the bleakness of corroding despair.

- Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust.

- The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

- Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

- Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that.

- The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy. The true neighbor will risk his position, his prestige, and even his life for the welfare of others.

- We must all learn to live together as brothers, or we will all perish together as fools.

- Forgiveness is not an occasional act; it is a permanent attitude.

- I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

- The function of education, therefore, is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. But education which stops with efficiency may prove the greatest menace to society. The most dangerous criminal may be the man gifted with reason but with no morals.

- I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the promised land.

- Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice. Justice at its best is love correcting everything that stands against love.

- A man who won’t die for something is not fit to live.

- At the center of non-violence stands the principle of love.

- Right, temporarily defeated, is stronger than evil triumphant.

- In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.

- Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

- Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Civil Rights Activists

Ethel Kennedy

MLK Almost Didn’t Say “I Have a Dream”

Huey P. Newton

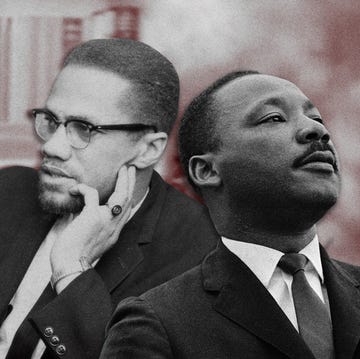

Martin Luther King Jr. Didn’t Criticize Malcolm X

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

30 Civil Rights Leaders of the Past and Present

Benjamin Banneker

Marcus Garvey

Madam C.J. Walker

Maya Angelou

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Martin Luther King Jr.

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 25, 2024 | Original: November 9, 2009

Martin Luther King Jr. was a social activist and Baptist minister who played a key role in the American civil rights movement from the mid-1950s until his assassination in 1968. King sought equality and human rights for African Americans, the economically disadvantaged and all victims of injustice through peaceful protest. He was the driving force behind watershed events such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the 1963 March on Washington , which helped bring about such landmark legislation as the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act . King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 and is remembered each year on Martin Luther King Jr. Day , a U.S. federal holiday since 1986.

When Was Martin Luther King Born?

Martin Luther King Jr. was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia , the second child of Martin Luther King Sr., a pastor, and Alberta Williams King, a former schoolteacher.

Along with his older sister Christine and younger brother Alfred Daniel Williams, he grew up in the city’s Sweet Auburn neighborhood, then home to some of the most prominent and prosperous African Americans in the country.

Did you know? The final section of Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech is believed to have been largely improvised.

A gifted student, King attended segregated public schools and at the age of 15 was admitted to Morehouse College , the alma mater of both his father and maternal grandfather, where he studied medicine and law.

Although he had not intended to follow in his father’s footsteps by joining the ministry, he changed his mind under the mentorship of Morehouse’s president, Dr. Benjamin Mays, an influential theologian and outspoken advocate for racial equality. After graduating in 1948, King entered Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania, where he earned a Bachelor of Divinity degree, won a prestigious fellowship and was elected president of his predominantly white senior class.

King then enrolled in a graduate program at Boston University, completing his coursework in 1953 and earning a doctorate in systematic theology two years later. While in Boston he met Coretta Scott, a young singer from Alabama who was studying at the New England Conservatory of Music . The couple wed in 1953 and settled in Montgomery, Alabama, where King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church .

The Kings had four children: Yolanda Denise King, Martin Luther King III, Dexter Scott King and Bernice Albertine King.

Montgomery Bus Boycott

The King family had been living in Montgomery for less than a year when the highly segregated city became the epicenter of the burgeoning struggle for civil rights in America, galvanized by the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954.

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks , secretary of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ( NAACP ), refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery bus and was arrested. Activists coordinated a bus boycott that would continue for 381 days. The Montgomery Bus Boycott placed a severe economic strain on the public transit system and downtown business owners. They chose Martin Luther King Jr. as the protest’s leader and official spokesman.

By the time the Supreme Court ruled segregated seating on public buses unconstitutional in November 1956, King—heavily influenced by Mahatma Gandhi and the activist Bayard Rustin —had entered the national spotlight as an inspirational proponent of organized, nonviolent resistance.

King had also become a target for white supremacists, who firebombed his family home that January.

On September 20, 1958, Izola Ware Curry walked into a Harlem department store where King was signing books and asked, “Are you Martin Luther King?” When he replied “yes,” she stabbed him in the chest with a knife. King survived, and the attempted assassination only reinforced his dedication to nonviolence: “The experience of these last few days has deepened my faith in the relevance of the spirit of nonviolence if necessary social change is peacefully to take place.”

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

Emboldened by the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, in 1957 he and other civil rights activists—most of them fellow ministers—founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), a group committed to achieving full equality for African Americans through nonviolent protest.

The SCLC motto was “Not one hair of one head of one person should be harmed.” King would remain at the helm of this influential organization until his death.

In his role as SCLC president, Martin Luther King Jr. traveled across the country and around the world, giving lectures on nonviolent protest and civil rights as well as meeting with religious figures, activists and political leaders.

During a month-long trip to India in 1959, he had the opportunity to meet family members and followers of Gandhi, the man he described in his autobiography as “the guiding light of our technique of nonviolent social change.” King also authored several books and articles during this time.

Letter from Birmingham Jail

In 1960 King and his family moved to Atlanta, his native city, where he joined his father as co-pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church . This new position did not stop King and his SCLC colleagues from becoming key players in many of the most significant civil rights battles of the 1960s.

Their philosophy of nonviolence was put to a particularly severe test during the Birmingham campaign of 1963, in which activists used a boycott, sit-ins and marches to protest segregation, unfair hiring practices and other injustices in one of America’s most racially divided cities.

Arrested for his involvement on April 12, King penned the civil rights manifesto known as the “ Letter from Birmingham Jail ,” an eloquent defense of civil disobedience addressed to a group of white clergymen who had criticized his tactics.

The 1968 Sanitation Workers’ Strike That Drew MLK to Memphis

With the slogan, "I am a man," workers in Memphis sought financial justice in a strike that fatefully became Martin Luther King Jr.'s final cause.

Behind Martin Luther King’s Searing ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’

King penned of the civil rights movement's seminal texts while in solitary confinement, initially on the margins of a newspaper.

How an Assassination Attempt Affirmed MLK’s Faith in Nonviolence

The civil rights leader was attacked in 1958 by Izola Ware Curry, a decade before his murder.

March on Washington

Later that year, Martin Luther King Jr. worked with a number of civil rights and religious groups to organize the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, a peaceful political rally designed to shed light on the injustices Black Americans continued to face across the country.

Held on August 28 and attended by some 200,000 to 300,000 participants, the event is widely regarded as a watershed moment in the history of the American civil rights movement and a factor in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 .

"I Have a Dream" Speech

The March on Washington culminated in King’s most famous address, known as the “I Have a Dream” speech, a spirited call for peace and equality that many consider a masterpiece of rhetoric.

Standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial —a monument to the president who a century earlier had brought down the institution of slavery in the United States—he shared his vision of a future in which “this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.'”

The speech and march cemented King’s reputation at home and abroad; later that year he was named “Man of the Year” by TIME magazine and in 1964 became, at the time, the youngest person ever awarded the Nobel Peace Prize .

In the spring of 1965, King’s elevated profile drew international attention to the violence that erupted between white segregationists and peaceful demonstrators in Selma, Alabama, where the SCLC and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had organized a voter registration campaign.

Captured on television, the brutal scene outraged many Americans and inspired supporters from across the country to gather in Alabama and take part in the Selma to Montgomery march led by King and supported by President Lyndon B. Johnson , who sent in federal troops to keep the peace.

That August, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act , which guaranteed the right to vote—first awarded by the 15th Amendment—to all African Americans.

Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

The events in Selma deepened a growing rift between Martin Luther King Jr. and young radicals who repudiated his nonviolent methods and commitment to working within the established political framework.

As more militant Black leaders such as Stokely Carmichael rose to prominence, King broadened the scope of his activism to address issues such as the Vietnam War and poverty among Americans of all races. In 1967, King and the SCLC embarked on an ambitious program known as the Poor People’s Campaign, which was to include a massive march on the capital.

On the evening of April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King was assassinated . He was fatally shot while standing on the balcony of a motel in Memphis, where King had traveled to support a sanitation workers’ strike. In the wake of his death, a wave of riots swept major cities across the country, while President Johnson declared a national day of mourning.

James Earl Ray , an escaped convict and known racist, pleaded guilty to the murder and was sentenced to 99 years in prison. He later recanted his confession and gained some unlikely advocates, including members of the King family, before his death in 1998.

After years of campaigning by activists, members of Congress and Coretta Scott King, among others, in 1983 President Ronald Reagan signed a bill creating a U.S. federal holiday in honor of King.

Observed on the third Monday of January, Martin Luther King Day was first celebrated in 1986.

Martin Luther King Jr. Quotes

While his “I Have a Dream” speech is the most well-known piece of his writing, Martin Luther King Jr. was the author of multiple books, include “Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story,” “Why We Can’t Wait,” “Strength to Love,” “Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?” and the posthumously published “Trumpet of Conscience” with a foreword by Coretta Scott King. Here are some of the most famous Martin Luther King Jr. quotes:

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

“Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”

“The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.”

“Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

“The time is always right to do what is right.”

"True peace is not merely the absence of tension; it is the presence of justice."

“Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

“Free at last, Free at last, Thank God almighty we are free at last.”

“Faith is taking the first step even when you don't see the whole staircase.”

“In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.”

"I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality. This is why right, temporarily defeated, is stronger than evil triumphant."

“I have decided to stick with love. Hate is too great a burden to bear.”

“Be a bush if you can't be a tree. If you can't be a highway, just be a trail. If you can't be a sun, be a star. For it isn't by size that you win or fail. Be the best of whatever you are.”

“Life's most persistent and urgent question is, 'What are you doing for others?’”

Photo Galleries

HISTORY Vault: Voices of Civil Rights

A look at one of the defining social movements in U.S. history, told through the personal stories of men, women and children who lived through it.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Humanities ›

- History & Culture ›

- The 20th Century ›

- People & Events ›

Biography of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Civil Rights Leader

- People & Events

- Fads & Fashions

- Early 20th Century

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- Women's History

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (January 15, 1929–April 4, 1968) was the charismatic leader of the U.S. civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. He directed the year-long Montgomery bus boycott , which attracted scrutiny by a wary, divided nation, but his leadership and the resulting Supreme Court ruling against bus segregation brought him fame. He formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to coordinate nonviolent protests and delivered over 2,500 speeches addressing racial injustice, but his life was cut short by an assassin in 1968.

Fast Facts: The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

- Known For : Leader of the U.S. civil rights movement

- Also Known As : Michael Lewis King Jr.

- Born : Jan. 15, 1929 in Atlanta, Georgia

- Parents : Michael King Sr., Alberta Williams

- Died : April 4, 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee

- Education : Crozer Theological Seminary, Boston University

- Published Works : Stride Toward Freedom, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?

- Awards and Honors : Nobel Peace Prize

- Spouse : Coretta Scott

- Children : Yolanda, Martin, Dexter, Bernice

- Notable Quote : "I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character."

Martin Luther King Jr. was born January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, to Michael King Sr., pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church, and Alberta Williams, a Spelman College graduate and former schoolteacher. King lived with his parents, a sister, and a brother in the Victorian home of his maternal grandparents.

Martin—named Michael Lewis until he was 5—thrived in a middle-class family, going to school, playing football and baseball, delivering newspapers, and doing odd jobs. Their father was involved in the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and had led a successful campaign for equal wages for White and Black Atlanta teachers. When Martin's grandfather died in 1931, Martin's father became pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, serving for 44 years.

After attending the World Baptist Alliance in Berlin in 1934, King Sr. changed his and his son's name from Michael King to Martin Luther King, after the Protestant reformist. King Sr. was inspired by Martin Luther's courage of confronting institutionalized evil.

Wikimedia Commons

King entered Morehouse College at 15. King's wavering attitude toward his future career in the clergy led him to engage in activities typically not condoned by the church. He played pool, drank beer, and received his lowest academic marks in his first two years at Morehouse.

King studied sociology and considered law school while reading voraciously. He was fascinated by Henry David Thoreau 's essay " On Civil Disobedience" and its idea of noncooperation with an unjust system. King decided that social activism was his calling and religion the best means to that end. He was ordained as a minister in February 1948, the year he graduated with a sociology degree at age 19.

In September 1948, King entered the predominately White Crozer Theological Seminary in Upland, Pennsylvania. He read works by great theologians but despaired that no philosophy was complete within itself. Then, hearing a lecture about Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi , he became captivated by his concept of nonviolent resistance. King concluded that the Christian doctrine of love, operating through nonviolence, could be a powerful weapon for his people.

In 1951, King graduated at the top of his class with a Bachelor of Divinity degree. In September of that year, he enrolled in doctoral studies at Boston University's School of Theology.

While in Boston, King met Coretta Scott , a singer studying voice at the New England Conservatory of Music. While King knew early on that she had all the qualities he desired in a wife, initially, Coretta was hesitant about dating a minister. The couple married on June 18, 1953. King's father performed the ceremony at Coretta's family home in Marion, Alabama. They returned to Boston to complete their degrees.

King was invited to preach in Montgomery, Alabama, at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, which had a history of civil rights activism. The pastor was retiring. King captivated the congregation and became the pastor in April 1954. Coretta, meanwhile, was committed to her husband's work but was conflicted about her role. King wanted her to stay home with their four children: Yolanda, Martin, Dexter, and Bernice. Explaining her feelings on the issue, Coretta told Jeanne Theoharis in a 2018 article in The Guardian , a British newspaper:

“I once told Martin that although I loved being his wife and a mother, if that was all I did I would have gone crazy. I felt a calling on my life from an early age. I knew I had something to contribute to the world.”

And to a degree, King seemed to agree with his wife, saying he fully considered her a partner in the struggle for civil rights as well as on all other issues with which he was involved. Indeed, in his autobiography, he stated:

"I didn't want a wife I couldn't communicate with. I had to have a wife who would be as dedicated as I was. I wish I could say that I led her down this path, but I must say we went down it together because she was as actively involved and concerned when we met as she is now."

Yet, Coretta felt strongly that her role, and the role of women in general in the civil rights movement, had long been "marginalized" and overlooked, according to The Guardian . As early as 1966, Corretta wrote in an article published in the British women's magazine New Lady:

“Not enough attention has been focused on the roles played by women in the struggle….Women have been the backbone of the whole civil rights movement.…Women have been the ones who have made it possible for the movement to be a mass movement.”

Historians and observers have noted that King did not support gender equality in the civil rights movement. In an article in The Chicago Reporter , a monthly publication that covers race and poverty issues, Jeff Kelly Lowenstein wrote that women "played a limited role in the SCLC." Lowenstein further explained:

"Here the experience of legendary organizer Ella Baker is instructive. Baker struggled to have her voice heard...by leaders of the male-dominated organization. This disagreement prompted Baker, who played a key role in the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee , to counsel young members like John Lewis to retain their independence from the older group. Historian Barbara Ransby wrote in her 2003 biography of Baker that the SCLC ministers were 'not ready to welcome her into the organization on an equal footing' because to do so 'would be too far afield from the gender relations they were used to in the church.'"

Montgomery Bus Boycott

When King arrived in Montgomery to join the Dexter Avenue church, Rosa Parks , secretary of the local NAACP chapter, had been arrested for refusing to relinquish her bus seat to a White man. Parks' December 1, 1955, arrest presented the perfect opportunity to make a case for desegregating the transit system.

E.D. Nixon, former head of the local NAACP chapter, and the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, a close friend of King, contacted King and other clergymen to plan a citywide bus boycott. The group drafted demands and stipulated that no Black person would ride the buses on December 5.

That day, nearly 20,000 Black citizens refused bus rides. Because Black people comprised 90% of the passengers, most buses were empty. When the boycott ended 381 days later, Montgomery's transit system was nearly bankrupt. Additionally, on November 23, in the case of Gayle v. Browder , the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that "Racially segregated transportation systems enforced by the government violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment," according to Oyez, an online archive of U.S. Supreme Court cases operated by the Illinois Institute of Technology's Chicago-Kent College of Law. The court also cited the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka , where it had ruled in 1954 that "segregation of public education based solely on race (violates) the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment," according to Oyez. On December 20, 1956, the Montgomery Improvement Association voted to end the boycott.

Buoyed by success, the movement's leaders met in January 1957 in Atlanta and formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to coordinate nonviolent protests through Black churches. King was elected president and held the post until his death.

Principles of Nonviolence

In early 1958, King's first book, "Stride Toward Freedom," which detailed the Montgomery bus boycott, was published. While signing books in Harlem, New York, King was stabbed by a Black woman with a mental health condition. As he recovered, he visited India's Gandhi Peace Foundation in February 1959 to refine his protest strategies. In the book, greatly influenced by Gandhi's movement and teachings, he laid six principles, explaining that nonviolence:

Is not a method for cowards; it does resist : King noted that "Gandhi often said that if cowardice is the only alternative to violence, it is better to fight." Nonviolence is the method of a strong person; it is not "stagnant passivity."

Does not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win his friendship and understanding : Even in conducting a boycott, for example, the purpose is "to awaken a sense of moral shame in the opponent" and the goal is one of "redemption and reconciliation," King said.

Is directed against forces of evil rather than against persons who happen to be doing the evil: "It is evil that the nonviolent resister seeks to defeat, not the persons victimized by evil," King wrote. The fight is not one of Black people versus White people, but to achieve "but a victory for justice and the forces of light," King wrote.

Is a willingness to accept suffering without retaliation, to accept blows from the opponent without striking back: Again citing Gandhi, King wrote: "The nonviolent resister is willing to accept violence if necessary, but never to inflict it. He does not seek to dodge jail. If going to jail is necessary, he enters it 'as a bridegroom enters the bride’s chamber.'"

Avoids not only external physical violence but also internal violence of spirit: Saying that you win through love not hate, King wrote: "The nonviolent resister not only refuses to shoot his opponent, but he also refuses to hate him."

Is based on the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice: The nonviolent person "can accept suffering without retaliation" because the resister knows that "love" and "justice" will win in the end.

Buyenlarge / Contributor / Getty Images

In April 1963, King and the SCLC joined Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights in a nonviolent campaign to end segregation and force Birmingham, Alabama, businesses to hire Black people. Fire hoses and vicious dogs were unleashed on the protesters by “Bull” Connor's police officers. King was thrown into jail. King spent eight days in the Birmingham jail as a result of this arrest but used the time to write "Letter From a Birmingham Jail," affirming his peaceful philosophy.

The brutal images galvanized the nation. Money poured in to support the protesters; White allies joined demonstrations. By summer, thousands of public facilities nationwide were integrated, and companies began to hire Black people. The resulting political climate pushed the passage of civil rights legislation. On June 11, 1963, President John F. Kennedy drafted the Civil Rights Act of 1964 , which was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson after Kennedy's assassination. The law prohibited racial discrimination in public, ensured the "constitutional right to vote," and outlawed discrimination in places of employment.

March on Washington

CNP / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

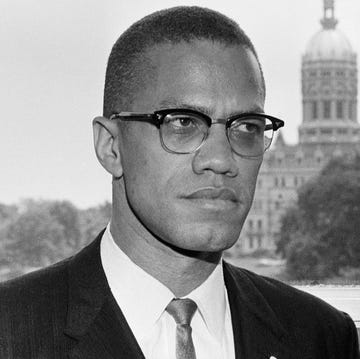

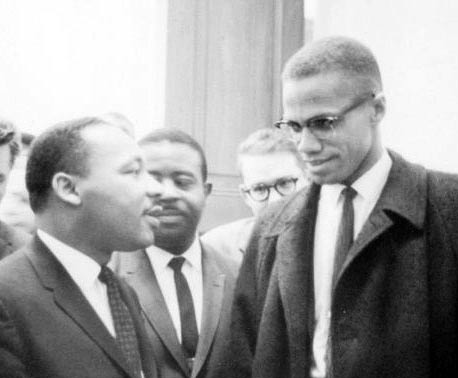

Then came the March on Washington, D.C ., on August 28, 1963. Nearly 250,000 Americans listened to speeches by civil rights activists, but most had come for King. The Kennedy administration, fearing violence, edited a speech by John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and invited White organizations to participate, causing some Black people to denigrate the event. Malcolm X labeled it the “farce in Washington."

Crowds far exceeded expectations. Speaker after speaker addressed them. The heat grew oppressive, but then King stood up. His speech started slowly, but King stopped reading from notes, either by inspiration or gospel singer Mahalia Jackson shouting, “Tell 'em about the dream, Martin!”

He had had a dream, he declared, “that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” It was the most memorable speech of his life.

Nobel Prize

King, now known worldwide, was designated Time magazine's “Man of the Year” in 1963. He won the Nobel Peace Prize the following year and donated the $54,123 in winnings to advancing civil rights.

Not everyone was thrilled by King's success. Since the bus boycott, King had been under scrutiny by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Hoping to prove King was under communist influence, Hoover filed a request with Attorney General Robert Kennedy to put him under surveillance, including break-ins at homes and offices and wiretaps. However, despite "various kinds of FBI surveillance," the FBI found "no evidence of Communist influence," according to The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University.

In the summer of 1964, King's nonviolent concept was challenged by deadly riots in the North. King believed their origins were segregation and poverty and shifted his focus to poverty, but he couldn't garner support. He organized a campaign against poverty in 1966 and moved his family into one of Chicago's Black neighborhoods, but he found that strategies successful in the South didn't work in Chicago. His efforts were met with "institutional resistance, skepticism from other activists and open violence," according to Matt Pearce in an article in the Los Angeles Times , published in January 2016, the 50th anniversary of King's efforts in the city. Even as he arrived in Chicago, King was met by "a line of police and a mob of angry white people," according to Pearce's article. King even commented on the scene:

“I have never seen, even in Mississippi and Alabama, mobs as hateful as I’ve seen here in Chicago. Yes, it’s definitely a closed society. We’re going to make it an open society.”

Despite the resistance, King and the SCLC worked to fight "slumlords, realtors and Mayor Richard J. Daley’s Democratic machine," according to the Times . But it was an uphill effort. "The civil rights movement had started to splinter. There were more militant activists who disagreed with King’s nonviolent tactics, even booing King at one meeting," Pearce wrote. Black people in the North (and elsewhere) turned from King's peaceful course to the concepts of Malcolm X.

King refused to yield, addressing what he considered the harmful philosophy of Black Power in his last book, "Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?" King sought to clarify the link between poverty and discrimination and to address America's increased involvement in Vietnam, which he considered unjustifiable and discriminatory toward those whose incomes were below the poverty level as well as Black people.

King's last major effort, the Poor People's Campaign, was organized with other civil rights groups to bring impoverished people to live in tent camps on the National Mall starting April 29, 1968.

Earlier that spring, King had gone to Memphis, Tennessee, to join a march supporting a strike by Black sanitation workers. After the march began, riots broke out; 60 people were injured and one person was killed, ending the march.

On April 3, King gave what became his last speech. He wanted a long life, he said, and had been warned of danger in Memphis but said death didn't matter because he'd "been to the mountaintop" and seen "the promised land."

On April 4, 1968, King stepped onto the balcony of Memphis' Lorraine Motel. A rifle bullet tore into his face . He died at St. Joseph's Hospital less than an hour later. King's death brought widespread grief to a violence-weary nation. Riots exploded across the country.

Win McNamee / Getty Images

King's body was brought home to Atlanta to lie at Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he had co-pastored with his father for many years. At King's April 9, 1968, funeral, great words honored the slain leader, but the most apropos eulogy was delivered by King himself, via a recording of his last sermon at Ebenezer:

"If any of you are around when I meet my day, I don't want a long funeral...I'd like someone to mention that day that Martin Luther King Jr. tried to give his life serving others...And I want you to say that I tried to love and serve humanity."

King had achieved much in the short span of 11 years. With accumulated travel topping 6 million miles, King could have gone to the moon and back 13 times. Instead, he traveled the world, making over 2,500 speeches, writing five books, and leading eight major nonviolent efforts for social change. King was arrested and jailed 29 times during his civil rights work, mainly in cities throughout the South, according to the website Face2Face Africa.

King's legacy today lives through the Black Lives Matter movement, which is physically nonviolent but lacks Dr. King's principle on "the internal violence of the spirit" that says one should love, not hate, their oppressor. Dara T. Mathis wrote in an April 3, 2018, article in The Atlantic, that King's legacy of "militant nonviolence lives on in the pockets of mass protests" of the Black Lives Matter movement throughout the country. But Mathis added:

"Conspicuously absent from the language modern activists use, however, is an appeal to America’s innate goodness, a call to fulfill the promise set forth by its Founding Fathers."

And Mathis further noted:

"Although Black Lives Matter practices nonviolence as a matter of strategy, love for the oppressor does not find its way into their ethos."

In 1983, President Ronald Reagan created a national holiday to celebrate the man who did so much for the United States. Reagan summed up King's legacy with these words that he gave during a speech dedicating the holiday to the fallen civil rights leader:

"So, each year on Martin Luther King Day, let us not only recall Dr. King, but rededicate ourselves to the Commandments he believed in and sought to live every day: Thou shall love thy God with all thy heart, and thou shall love thy neighbor as thyself. And I just have to believe that all of us—if all of us, young and old, Republicans and Democrats, do all we can to live up to those Commandments, then we will see the day when Dr. King's dream comes true, and in his words, 'All of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning,...land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim's pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.'"

Coretta Scott King, who had fought hard to see the holiday established and was at the White House ceremony that day, perhaps summed up King's legacy most eloquently, sounding wistful and hopeful that her husband's legacy would continue to be embraced:

"He loved unconditionally. He was in constant pursuit of truth, and when he discovered it, he embraced it. His nonviolent campaigns brought about redemption, reconciliation, and justice. He taught us that only peaceful means can bring about peaceful ends, that our goal was to create the love community.

"America is a more democratic nation, a more just nation, a more peaceful nation because Martin Luther King, Jr., became her preeminent nonviolent commander."

Additional References

- Abernathy, Ralph David. "And the Walls Came Tumbling Down: An Autobiography." Paperback, Unabridged edition, Chicago Review Press, April 1, 2010.

- Branch, Taylor. "Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63." America in the King Years, Reprint edition, Simon & Schuster, November 15, 1989.

- Brown v. Board of Education Topeka . oyez.org.

- “ Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) .” The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute , 21 May 2018.

- Gayle v. Browder . oyez.org.

- Garrow, David. "Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference." Paperback, Reprint edition, William Morrow Paperbacks, January 6, 2004.

- Hansen, Drew. " Mahalia Jackson and King's Improvisation . ” The New York Times, Aug. 27, 2013.

- Lowenstein, Jeff Kelly. “ Martin Luther King Jr., Women, and the Possibility of Growth .” Chicago Reporter , 21 Jan. 2019.

- McGrew, Jannell. “ The Montgomery Bus Boycott: They Changed the World .

- “Principles of Nonviolent Resistance By Martin Luther King Jr.” Resource Center for Nonviolence , 8 Aug. 2018.

- “ Remarks on Signing the Bill Making the Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr., a National Holiday .” Ronald Reagan , reaganlibrary.gov/archive.

- Theoharis, Jeanne. “' I Am Not a Symbol, I Am an Activist': the Untold Story of Coretta Scott King .” The Guardian , Guardian News and Media, 3 Feb. 2018.

- X, Malcolm. "The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley." Alex Haley, Attallah Shabazz, Paperback, Reissue edition, Ballantine Books, November 1992.

Michael Eli Dokos. “ Ever Knew Martin Luther King Jr. Was Arrested 29 Times for His Civil Rights Work? ” Face2Face Africa , 23 Feb. 2020.

- Martin Luther King Jr. Quotations

- Famous Black American Men and Women of the 20th Century

- 7 20th Century Men Who Made History

- Biography of Fats Waller, Jazz Artist

- Biography of Mohandas Gandhi, Indian Independence Leader

- Biography of Hubert Humphrey, the Happy Warrior

- Jackie Robinson

- Gerald Ford: President of the United States, 1974-1977

- Biography of Pancho Villa, Mexican Revolutionary

- Biography of Walter Cronkite, Anchorman and TV News Pioneer

- Biography of Tom Hayden, Activist and Politician

- Biography of John F. Kennedy Jr.

- Adlai Stevenson: American Statesman and Presidential Candidate

- Frances Perkins: The First Woman to Serve in a Presidential Cabinet

- Biography of Booker T. Washington, Early Black Leader and Educator

- Biography of Saddam Hussein, Dictator of Iraq

The life of Martin Luther King Jr.

Photo galleries.

- = Key moments in MLK's life and beyond

- = Key moments in the Civil Rights Movement and beyond

- Jan. 15: Michael Luther King Jr., later renamed Martin, is born to schoolteacher Alberta King and Baptist minister Michael Luther King in Atlanta, Ga.

- King graduates from Morehouse College in Atlanta with a B.A.

- Graduates with a B.D. from Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pa.

- June 18: King marries Coretta Scott in Marion, Ala. They will have four children: Yolanda Denise (b.1955), Martin Luther King III (b.1957), Dexter (b.1961), Bernice Albertine (b.1963).

- Brown vs. Board of Education: U.S. Supreme Court bans segregation in public schools.

- September: King moves to Montgomery, Ala., to preach at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.

- After coursework at New England colleges, King finishes his Ph.D. in systematic theology.

- Bus boycott launches in Montgomery, Ala., after an African-American woman, Rosa Parks, is arrested December 1 for refusing to give up her seat to a white person.

- Jan. 26: King is arrested for driving 30 mph in a 25 mph zone.

- Jan. 30: King's house is bombed.

- Dec. 21: After more than a year of bus boycotts and a legal fight, the Montgomery buses desegregate.

- January: Black ministers form what becomes known as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. King is named first president one month later.

- In this typical year of demonstrations, King travels 780,000 miles and makes 208 speeches.

- Garfield High School becomes the first Seattle high school with a more than 50 percent nonwhite student body.

- At previously all-white Central High in Little Rock, Ark., 1,000 paratroopers are called by President Eisenhower to restore order and escort nine black students.

- King's first book, "Stride Toward Freedom," is published, recounting his recollections of the Montgomery bus boycott. While King is promoting his book in a Harlem book store, an African American woman stabs him.

- King visits India. He had a lifelong admiration for Mohandas K. Gandhi, and credited Gandhi's passive resistance techniques for his civil-rights successes.

- King leaves for Atlanta to pastor his father's church, Ebenezer Baptist Church.

- The sit-in protest movement begins in February at a Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C. and spreads across the nation.

- Freedom rides begin from Washington, D.C: Groups of black and white people ride buses through the South to challenge segregation.

- King makes his only visit to Seattle. He visits numerous places, including two morning assemblies at Garfield High School.

- King meets with President John F. Kennedy to urge support for civil rights.

- Blacks become the majority at Garfield High, 51 percent of the student population - a first for Seattle. The school district average is 5.3 percent.

- Two killed, many injured in riots as James Meredith is enrolled as the first black at the University of Mississippi.

- King leads protests in Birmingham for desegregated department store facilities, and fair hiring.

- April: Arrested after demonstrating in defiance of a court order, King writes "Letter From Birmingham Jail." This eloquent letter, later widely circulated, becomes a classic of the civil-rights movement.

- Police arrest King and other ministers demonstrating in Birmingham, Ala., then turn fire hoses and police dogs on the marchers.

- June 12: Medgar Evers, NAACP leader, is murdered as he enters his home in Jackson, Miss.

- About 1,300 people march from the Central Area to downtown Seattle, demanding greater job opportunities for blacks in department stores. The Bon Marche promises 30 new jobs for blacks.

- About 400 people rally at Seattle City Hall to protest delays in passing an open-housing law. In response, the city forms a 12-member Human Rights Commission but only two blacks are included, prompting a sit-in at City Hall and Seattle's first civil-rights arrests.

- Aug. 28: 250,000 civil-rights supporters attended the March on Washington. At the Lincoln Memorial, King delivers the famous "I have a dream" speech.

- 250,000 people attend the March on Washington, D.C. urging support for pending civil-rights legislation. The event is highlighted by King's "I have a dream" speech.

- The Seattle School District implements a voluntary racial transfer program, mainly aimed at busing black students to mostly white schools.

- Sep. 15: Four girls are killed in a bombing at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala.

- Seattle City Council agrees to put together an open-housing ordinance but insists on putting it on the ballot. Voters defeat it by a 2-to-1 ratio. It will be four more years before an open-housing ordinance becomes law.

- Three civil-rights workers are murdered in Mississippi.

- July 2: President Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

- King's book "Why We Can't Wait" is published.

- King visits with West Berlin Mayor Willy Brant and Pope Paul VI.

- Dec. 10: King wins the Nobel Peace Prize.

- Out of 955 people employed by the Seattle Fire Department, just two are African American, and only one is Asian, account for less than 0.2 and 0.1 percent of the force, respectively. By the end of 1993, the department is 12.2 percent African American and 5.6 percent Asian.

- Jan. 18: King successfully registers to vote at the Hotel Albert in Selma, Ala. and is assaulted by James George Robinson of Birmingham.

- February: King continues to protest discrimination in voter registration and is arrested and jailed. He meets with President Lyndon B. Johnson Feb. 9 and other American leaders about voting rights for African Americans.

- Feb. 21: Malcolm X is murdered. Three men are convicted of his murder.

- Mar. 16-21: King and 3,200 people march from Selma to Montgomery

- Aug. 6: President Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The act, which King sought, authorizes federal examiners to register qualified voters and suspends devices such as literacy tests that aimed to prevent African Americans from voting.

- Aug. 11-16: Watts riots leave 34 dead in Los Angeles.

- Apr. 4: King is assassinated in Memphis, Tenn., by James Earl Ray, unleashing violence in more than 100 cities.

- In response to King's death, Seattle residents hurl firebombs, broke windows, and pelt motorists with rocks. Ten thousand people also march to Seattle Center for a rally in his memory.

- Aaron Dixon becomes first leader of Black Panther Party branch in Seattle.

- There is a rally at Garfield High in support of Dixon, Larry Gossett, and Carl Miller, sentenced to six months in the King County Jail for unlawful assembly in an earlier demonstration. Before the speakers finish, firebombs and rocks begin flying toward cars coming down 23rd Avenue. Sporadic riots break out in Seattle's Central Area during the summer.

- Edwin Pratt, executive director of the Seattle Urban League and a moderate and respected African American leader, is shot to death while standing in the doorway of his home. The murder is never solved.

- Seattle School Board adopts a plan designed to eliminate racial imbalance in schools by fall 1979.

- Seattle becomes the largest city in the United States to desegregate its schools without a court order; nearly one-quarter of the school district's students are bused as part of the "Seattle Plan." Two months later, voters pass an anti-busing initiative. It is later ruled unconstitutional.