- American History

The 10 Cruelest Human Experimentation Cases in History

“First, do no harm,” is the oath taken by physicians the world over. And this has been the case for centuries now. For the most part, these men and women of science stay faithful to this oath, even defying orders to the contrary. But sometimes they not only break it, they do so in the worst way imaginable. There have been numerous instances of doctors and other scientists going way beyond the limitations of what’s moral or ethical in the name of ‘progress’. They have used humans as experimental guinea pigs for their tests.

In many cases, the test subjects were either kept in ignorance about what an experiment involved or they were simply in no position to offer their resistance or consent. Of course, it may well be the case that such dubious methods produced results. Indeed, some of the most controversial experiments of the past century produced results that continue to inform scientific understanding to this day. But that will never mean such experiments will be seen as just. Sometimes, the perpetrators of cruel research lose their good names or reputations. Sometimes they are prosecuted for their attempts to ‘play God’. Or sometimes they just get away with it.

You might want to brace yourself as we look at the ten weirdest and cruelest human experiments carried out in history:

Dr. Shiro Ishii and Unit 731

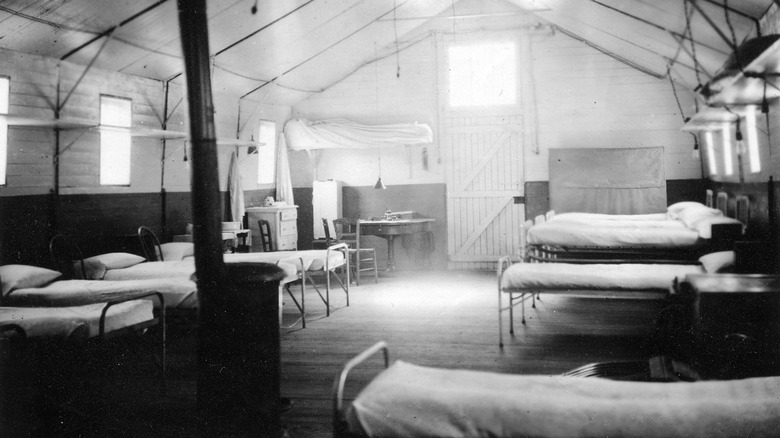

During World War II, Imperial Japan committed a number of crimes against humanity. But perhaps few were crueler than the experiments that were conducted at Unit 731. Part of the Imperial Japanese Army, this was a super-secret unit dedicated to undertaking research into biological and chemical weapons. Quite simply, the Imperial authority wanted to build weapons that were deadlier – or just crueler – than anything that had gone before. And they weren’t opposed to using human guinea pigs to test their creations.

Based in Harbon, the biggest city of Manchuko, the part of north-east China that Japan made its puppet state, Unit 731 was constructed between 1934 and 1939. Overseeing its construction was General Shiro Ishii. Though he was a medical doctor, Ishii was also a fanatical soldier and so he was happy to set his ethics aside in the name of total victory for Imperial Japan. In all, it’s estimated that as many as 3,000 men, women and children were used as forced participants in the experiments conducted here. For the most part, the horrific tests were carried out on Chinese people, though prisoners-of-war, including men from Korea and Mongolia, were used.

For more than five years, General Ishii oversaw a wide range of experiments, many of them of dubious medical value to say the least. Thousands were subjected to vivisections, usually without anaesthetic. Often, these were fatal. Countless types of surgery, including brain surgery and amputations, were also carried out without anaesthetic. At other times, inmates were injected directly with diseases such as syphilis and gonorrhoea, or with chemicals used in bombs. Other twisted experiments included tying men up naked outside and observing the effects of frostbite, or simply starving people and seeing how long they took to die.

Once it was clear Japan was going to lose the war, General Ishii tried to destroy all evidence of the tests. He burned down the facilities and swore his men to silence. He needn’t have worried. Senior researchers from Unit 731 were granted immunity by the U.S. In exchange, they contributed their knowledge to America’s own biological and chemical weapons programs. For decades, any stories of atrocities were dismissed as ‘Communist Propaganda’. In more recent years, the Japanese government has acknowledged the Unit’s existence as well as its work, though it maintains most official records have been lost to history.

NEXT >>

“The Little Albert Experiment”

After many months observing young children, John Hopkins University psychologist Dr. John B. Watson concluded that infants could be conditioned to be scared of non-threatening objects or stimuli. All he needed was first-hand proof. Since it was 1919 and experimental ethics were nowhere near as strict as they are today, Watson, along with his graduate student Rosalie Rayner, set about designing an experiment to test their theory. Thanks to their connections at the Baltimore hospital, they were able to find a young baby, named ‘Albert’, and ‘borrow’ him for the afternoon. While Albert’s mother might have consented to her son helping out scientific research, she had no idea what Watson was actually planning.

The young Albert was just nine months old when he was taken from a hospital and put to work as Watson’s guinea pig. At first, Watson carried out a series of baseline tests, to see that the child was indeed emotionally stable and at the accepted stage of development. But then the tests got creepier. Albert was shown several furry animals. These included a dog, a white rat and a rabbit. Watson would show these toys to Albert while at the same time banging a hammer against a metal bar. This was repeated a number of times. Before long, Albert was associating the sight of the furry animals with the fear provoked by the loud, unpleasant noise. Indeed, within just a short space of time, just seeing the furry rat could distress the child.

Watson noted at the time: “The instant the rat was shown, the baby began to cry. Almost instantly he turned sharply to the left, fell over on [his] left side, raised himself on all fours and began to crawl away so rapidly that he was caught with difficulty before reaching the edge of the table.” The scientist and his research partner had achieved their goal: they had proof that, just as in animals, classical conditioning can be used to influence or even dictate emotional responses in humans. Watson published his findings the following year, in the prestigious Journal of Experimental Psychology .

Even at the time, Watson’s methods were seen as unethical. After all, isn’t a doctor supposed to ‘do no harm’? What’s more, Watson never worked with Little Albert again, so he wasn’t able to reverse the process. But still, the results were heralded as a breakthrough in our understanding of popular psychology. Notably, Watson recorded the Little Albert Experiment, and the videos can be seen online today. And, for what it’s worth, most experts now agree that, though he would have most likely feared furry objects for a short spell of time during his childhood, Little Albert probably lost the association between cute toys and loud noises.

<< Previous

The “Monster” Study

These days, any tests carried out on children are subject to strict ethical rules and guidelines. This wasn’t the case back in the 1930s, however. So, when Wendell Johnson, a speech pathologist at the University of Iowa, wanted to carry out research on young participants, his institution was happy to oblige. Along with Mary Tudor, a grad student Johnson was supervising, work began in 1939. Over the next few years, dozens of kids would be subject to speech-related tests, with the effects of the experiment lasting for decades.

The purpose of the research sounded noble enough: Johnson wanted to see how a child’s upbringing affects their speech. In particular, he was fascinated by stuttering and determined to see what made one child stutter, yet another speak fluently. Thankfully, a local orphanage was able to ‘supply’ Johnson and Tudor with 22 children for them to work with. All of the young participants spoke without a stutter when they arrived at the University of Iowa labs for the first time. They were then divided into two equal groups, and the experiment got underway.

Both groups were asked to speak for the researchers. How they were treated, however, was completely different. In the first group, all of the children received positive feedback. They were praised for their fluent speech and command of the English language. The second group received the opposite kind of treatment. They were ridiculed for their inability to speak like adults. Johnson and Tudor would listen carefully for any little mistakes, and above all for any signs of stuttering, and criticize the children harshly for them.

Johnson’s methods shocked his academic peers. Not that they would have been so surprised. As a young researcher at the University of Iowa, he gained a reputation for experimenting with shock tactics. For instance, as a postgraduate student himself, Johnson would work with his colleagues trying to cure his own stutter, even electrocuting himself to see if that made a difference. But still, inflicting deliberate cruelty on children was seen as a step too far. As such, the Iowan academics nicknamed Johnson’s 1939 research ‘The Monster Study’. And the name was just about the only thing of significance it gave us.

With the University of Iowa keen to distances itself from news of human experimentation being carried out by the Nazis in war-torn Europe, they hushed-up the Monster Study. None of the findings were ever published in any academic journal of note. Only Johnson’s own thesis remains. The effects were clear, however. Many of the children in the second group went on to develop serious stutters. Some even had serious speech problems for the rest of their lives. The university finally acknowledged the experiment in 2001, apologising to those involved. Then, in 2007, six of the original orphan kids were awarded almost $1 million in compensation for the psychological impact Johnson’s work had on them.

Interestingly, however, while the methods used for the Monster Study have widely been condemned as being cruel and simply indefensible, some have argued that Johnson may have been onto something. Certainly, Mary Tudor said before her death that she and her research partner might have made serious contributions to our understanding of speech and speech pathology had they been allowed to publish their work. Instead, the experiment is now shorthand for bad science and a complete lack of ethics.

The Stanford Prison Experiment

Off all the ill-advised – and indeed, cruel – experiments North American universities have carried out over the decades, none is more infamous than the Stanford Prison Experiment. It’s so famous, in fact, that movies have been made based on the experiment which took place at Stanford University for one week in August 1971. Furthermore, while undoubtedly cruel, its findings are still used to inform popular understanding of psychological manipulation. Moreover, the behaviour of the participants involved is often held up as a warning about what can happen if humans are given power without accountability.

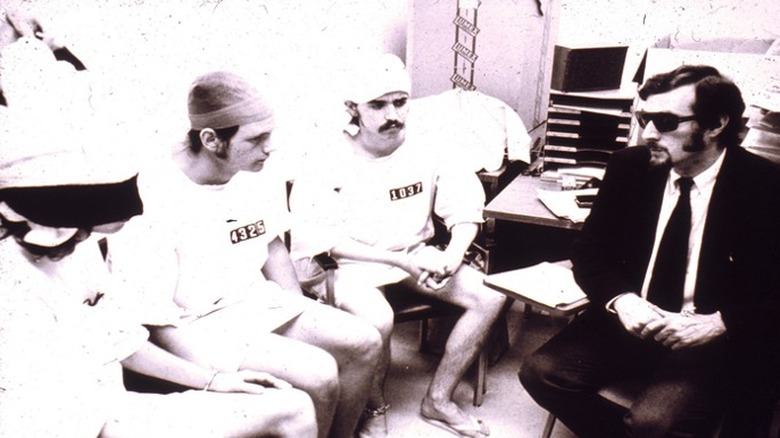

The experiment was led by Professor Phillip Zimbrano. As a psychologist, he was eager to see whether abuse in prisons can be explained by the inherent psychological traits of both guards and prisoners. Given the topic, he received funding from the U.S. Office of Naval Research. Funding in hand, Zimbrano set about recruiting participants. This turned out to be no problem at all, as a number of Stanford students volunteered to take part. Zimbrano then appointed some of the volunteers as guards and the others were designated as prisoners. The experiment could begin.

In the basement of the university’s psychology department, Zimbrano had built a makeshift ‘prison’. In all, 12 prisoners were kept here in small cells, while 12 guards were assigned a different part of the basement. While the prisoners had to endure tough conditions, the guards enjoyed comfortable, furnished quarters. The participants were also dressed for their parts, with the guards given uniforms and wooden batons. They were also kitted out with dark sunglasses so they could avoid eye contact with the people they were tasked with guarding.

Within 24 hours, any semblance of calm had gone. The prisoners started to revolt and the guards started to react. Special cells were set up to give well-behaving prisoners preferential treatment. The guards – who were barred from actually physically hitting their charges – started to use psychological methods to keep prisoners down. They would deny them food or put prisoners in darkened cells. Sleep was also denied to the prisoners. Within six days, Zimbrano agreed to halt the experiment. He did, at least, have more than enough evidence – some of it filmed – to draw on when making his conclusions.

Professor Zimbrano noted that around one third of the guards – again, young men taken randomly from the Stanford student population – exhibited genuine sadistic tendencies. At the same time, most of the inmates were seen to ‘internalise’ their roles. They took on the mentality of prisoners. While they could have left at any time, they instead gave up and became weak and passive. In the end, the experiment received, and continues to receive, criticism for the harsh methods used. Nevertheless, the findings of the Stanford Prison Experiment actually changed the way U.S. prisons are run and they are often held up as proof that most people can inflict cruelty and suffering on another human being if they are given a position of power and ordered to do so.

The South African ‘Aversion Project’

In Apartheid-era South Africa, national service was compulsory for all white males. At the same time, homosexuality was classed as a crime. Inevitably, therefore, any gay men who found themselves called into service were in for a tough time. But it wasn’t just name-calling or casual discrimination they had to contend with. Many were subjected to cruel experiments. The so-called ‘Aversion Project’, run throughout the 1970s and then the 1980s, was aimed at ‘treating’ homosexuals. As well as psychological treatments, it also used physical ‘treatments’, many of which would rightly be regarded as torture.

The project first really got started in 1969, with the creation of Ward 22. The creepily-named ward was part of a larger military hospital just outside of Pretoria and was designed to treat mentally-ill soldiers. For the unit chief Dr Aubrey Levin, this including homosexuals, regarded as unstable, or even ‘deviants’. For the most part, the doctor was determined to prove that electric shock therapy and conditioning could ‘cure’ the patients of their desires. Hundreds of men were electrocuted, often while being forced to look at pictures of gay men. The electric current would then be turned off and pictures of naked women shown instead in the hope that this would alter the mindset.

Inmates subjected to such experimental treatment would sometimes be tested, given temptations to see if they really were ‘cured’. Persistent ‘offenders’ were given hormone treatments, almost always against their will, and many were even chemically castrated. Even by the middle of the 1970s, when numerous, more ethical, studies had proven that ‘conversion therapies’ could change a person’s sexuality, Ward 22 carried on with its work. In fact, in only ended with the fall of the apartheid regime. To the very end of the project, Dr Levin maintained that all the men he treated were volunteers and asked for his help. Many of his peers disagreed, as did a judge, who sentenced him to five years in prison in 2014.

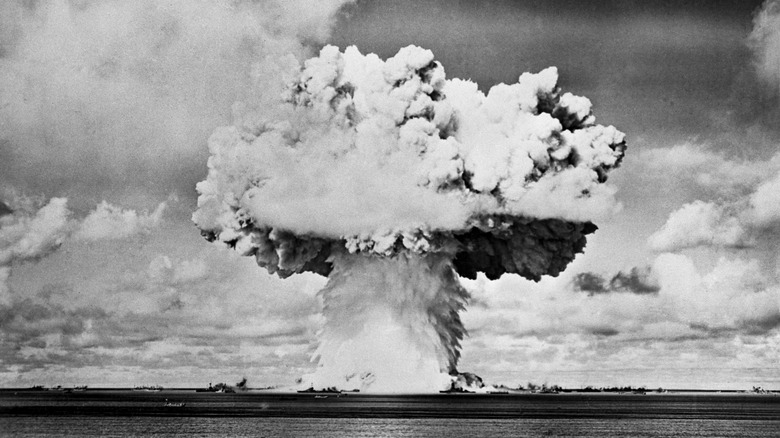

Project 4.1

On March 1, 1954, the United States carried out Castle Bravo , testing a nuclear bomb on the Bikini Atoll, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. The test not only went without a hitch, it actually went better than expected. The yield produced by the bomb was much higher than scientists had anticipated. At the same time, the weather conditions in this part of the Pacific turned out to be different to what had been predicted. Radiation fallout from the blast was blown upwind, towards the Marshall Islands. But, instead of alerting the islanders to the danger, the project heads sensed an opportunity. How many times would they be able to see the affect of radiation fallout on a population for real?

Making the most of the opportunity, the American scientists simply sat back an observed. That is, they watched innocent people be affected by the fallout of an American nuclear bomb. Over the next decade, the project observers noted an upturn in the number of women on the Marshall Islands suffering miscarriages or stillbirths. But then, after ten years or so, this spike ended. Things seemingly returned to normal, and so scientists were unable – or unwilling – to make any formal conclusions. But then, things started to go downhill again.

At first, children on the Marshall Islands were observed to be growing less than would be expected. But then, it became clear that not only were they suffering from stunted growth, but a higher-than-expected proportion of youngsters were developing thyroid cancer. What’s more, by 1974, the data was showing that one in three islanders had developed at least one tumor. Later analysis, published in 2010, estimated that around half of all cancer cases recorded on the Marshall Islands could be attributed to the 1954 nuclear test, even if people never displayed any obvious signs of radiation poisoning in the immediate aftermath of the explosion.

Given that the initial findings of Project 4.1 as it was known were published in professional medical journals as early as 1955, the American government has never really denied that the experiment took place. Rather, what has been, and continues to be contested, is whether the U.S. actually knew that the islands would be affected before they carried out the test. Many on the Marshall Islands believe that Project 4.1 was premeditated, while the American authorities maintain that it was improvised in the wake of the explosion. The debate continues to rage.

The Tuskegee Experiments

For four decades, African-American men in Macon County, Alabama, were told by medical researchers that they had ‘bad blood’. The scientists knew that this was a term used by sharecroppers in this part of the country to refer to a wide range of ailments. They knew, therefore, that they wouldn’t question the prognosis. And neither would they raise any concerns or questions when the same researchers gave them injections. Which is how doctors working on behalf of the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) were able to look on as hundreds of men went mad, blind or even died as a result of untreated syphilis.

When the experiment began back in 1932, there was no known cure for syphilis. As such, PHS researchers were determined to make a breakthrough. They went to Tuskegee College in Alabama and enlisted their help. Together, they enlisted 622 African-American men, almost all of them very poor. Of these men, 431 had already contracted syphilis prior to 1932, with the remaining 169 free from the disease. The men were told that the experiment would last for just six years, during which time they would be provided with free meals and medical care as doctors observed the development of the disease.

In 1947, penicillin became the recommended treatment for syphilis. Surely the doctors would give this to the men participating in the Tuskegee Experiment? Not so. Even though they knew the men could be cured, the PHR workers only gave them placebos, including aspirin and even combinations of minerals. With their condition untreated, the men slowly succumbed to syphilis. Some went blind, others went insane, and some died within a few years. What’s more, in the years after 1947, 19 syphilitic children were born to men enrolled in the study.

It was only in the mid-1960s that concerns started to be raised about the morality of the experiment. San Francisco-based PHS researcher Peter Buxton learned about what was happening in Alabama and raised his concerns. However, his superiors were unresponsive. As a result, Buxton leaked the story to a journalist friend. The story broke in 1972. Unsurprisingly, the public were outraged. The experiment was halted immediately, and the Congress inquiries began soon after. The surviving participants, as well as the children of those men who had died, were awarded $10 million in an out-of-court settlement. Finally, in 1993, President Bill Clinton offered a formal and official apology on behalf of the U.S. government to everyone affected by the experiment.

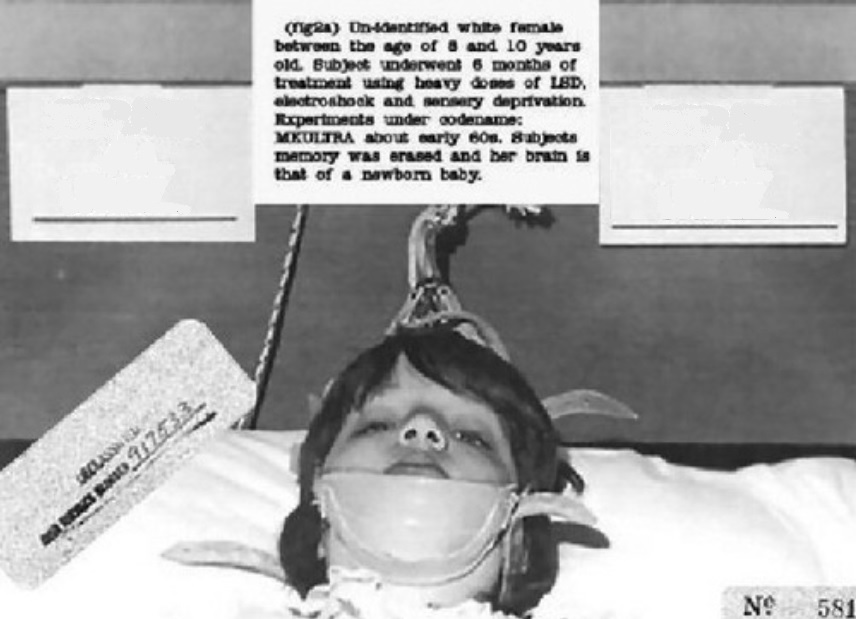

Project MK-Ultra

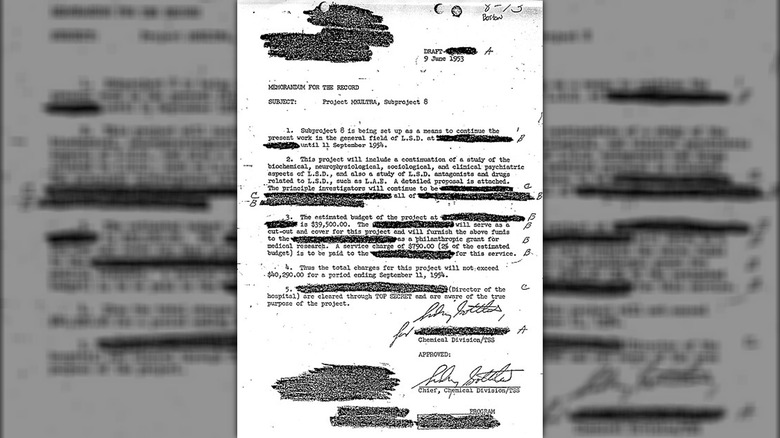

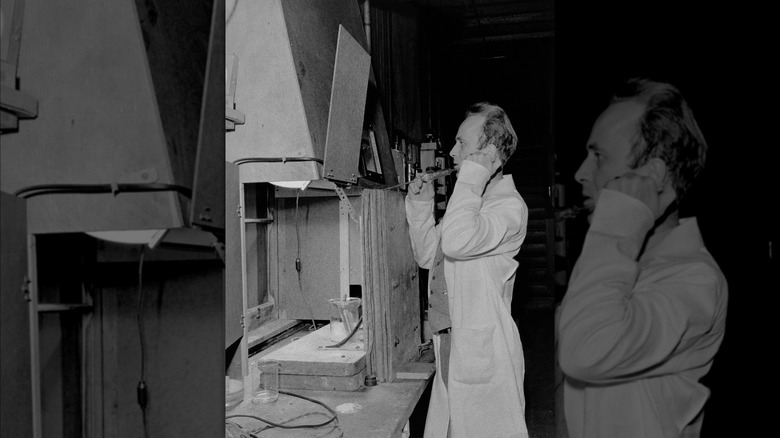

Though they had the Bomb, in the 1950s, the CIA were still determined to enjoy every advantage over their enemies. To achieve this, they were willing to think outside of the box. Perhaps the best example of this was MK-Ultra, a top-secret project where the CIA attempted to alter brain function and explore the possibility of mind control. While much of the written evidence, including files and witness testimonies, were destroyed soon after the experiments were brought to an end, we do know that the project involved a lot of drugs, some sex and countless instances of rule bending and breaking.

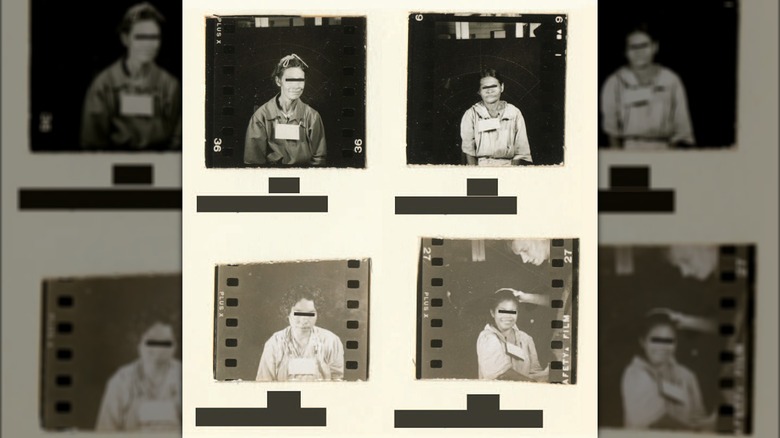

Project MK-Ultra was kick-started by the Office of Scientific Experiments at the start of the 1950s. Central to the project was determining how LSD affects the mind – and, more importantly, whether this could be turned to America’s advantage. In order to learn more, hundreds, perhaps even thousands of individuals, were given doses of the drug. In almost all cases, they were given LSD without their explicit knowledge or consent. For example, during Operation Midnight Climax in the early 1960s, the CIA opened up brothels. Here, the male clients were dosed up with LSD and then observed by scientists through one-way mirrors.

The experiments also included subjecting American citizens to sleep deprivation and hypnosis. Not all of the tests went plainly. Several people died as a direct result of Project MK-Ultra, including a US Army biochemist by the name of Frank Olsen. In 1953, the scientist was given a dose of LSD without his knowledge and, just a week later, died after jumping out of a window. While the official reason of his death was recorded as suicide, Olsen’s family have always maintained that he was effectively killed by the CIA.

When President Gerald Ford launched a special Commission on CIA activities in the United States, the work of Project MK-Ultra came to light. Two years previously, however, the-then Director of the CIA, Richard Helms, had ordered all files relating to the experiments to be destroyed. Witness testaments show that around 80 institutions were involved in the experiments, with thousands of people given hallucinogenic drugs, usually by CIA officers with no medical background. And so, in the end, was it all worth it? The CIA has acknowledged that the experiments produced nothing of real, scientific value. Project MK-Ultra has, however, lived on in the popular imagination and has inspired numerous books, video games and movies.

Guatemalan Syphilis Experiment

For more than two years in the middle of the 20 th century, the United States worked directly with the health ministries of Guatemala to infect thousands of people with a range of sexually transmitted diseases, above all syphilis. Since they wanted to do this without the study subjects knowing about it – after all, who would give their consent to being injected with syphilis? – it was decided that the experiment should take place in Guatemala, with soldiers and the most vulnerable members of society to serve as the guinea pigs.

The Guatemalan Syphilis Experiment (it was not given an official codename or even a formal project title) began in 1946. It was headed up by John Charles Cutler of the US Public Health Service (PHS). Despite being a physician himself, Cutler was happy to overlook the principle of ‘First, do no harm’ in order to carry out his work. Making use of local health clinics, he tasked his staff with infecting around 5,500 subjects. Most of them were soldiers or prisoners, though mental health patients and prostitutes were also used to see how syphilis and other diseases affect the body. Children living in orphanages were even used for the experiments.

In all cases, the subjects were told they were getting medication that was good for them. And, while all subjects were given antibiotics, an estimated 83 people died. In 1948, with the wider medical community hearing rumors of what was being done in Central America, and with the American government wary of the potential fallout, the experiments were brought to an abrupt end. Cutler would go on to carry out similar experiments in Alabama, though even here he stopped short of actually infecting his subjects with life-threatening diseases.

It was only in 2010, however, that the United States government issued a formal apology to Guatemala for the experiments it carried out in the 1940s. What’s more, President Barack Obama called the project “a crime against humanity”. That didn’t mean that the victims could get compensation, however. In 2011, several cases were put forward but then rejected, with the presiding judge noting that the U.S. government could not be held liable for actions carried out in its name outside of the country. A $1 billion lawsuit against the John Hopkins University and against the Rockefeller Foundation is still open.

Mengele’s Twins

A world at war gave the Nazi regime the ideal cover under which they would carry out some of the most horrific human experiments imaginable. At Auschwitz concentration camp, Dr Josef Mengele made full use of the tens of thousands of prisoners available to him. He would carry out unnecessarily cruel and unusual experiments, often with little or no scientific merit. And, above all, he was fascinated with twins. Or, more precisely, with identical twins. These would be the subjects of his most gruesome experiments.

Mengele would personally select prospective subjects from the ramps leading off the transport trains at the entrance to the concentration camp. Initially, his chosen twins were provided with relatively comfortable accommodation, as well as more generous rations than the rest of the inmate population. However, this was just a temporary respite. Mengele’s experiments were as varied as they were horrific. He would amputate one twin’s limbs and then compare the growth of both over the following days. Or he would infect one twin with a disease like typhoid. When they died, he would kill the healthy twin, too, and then compare their bodies.

Gruesomely, the records show that on one particularly bloody night, Mengele injected chloroform directly into the heart of 14 sets of twins. All died almost immediately. Another infamous tale tells of Mengele trying to create his own conjoined twins: he simply stitched two young Romani children back-to-back. They both died of gangrene after several long and painful days. Mengele also had a team of assistants working for him, and they were no less cruel.

Nobody will ever know just how many children or adults were victims of Mengele’s experiments. Despite being meticulous record keepers, the Nazis kept some things secret. Tragically for his victims and their relatives, Mengele never faced justice for his actions. He was smuggled out of Europe by Nazi sympathisers at the end of the war and lived for another 30 years, in hiding, in South America.

Where did we find this stuff? Here are our sources:

“Unmasking Horror: A special report.; Japan Confronting Gruesome War Atrocity”. Nicholas D. Kristof, The New York Times, 1995.

“Little Albert regains his identity”. American Psychology Association, 2010.

“Unit 731: Japan discloses details of notorious chemical warfare division”. Justin McCurry, The Guardian, April 2018.

“The Stuttering Doctor’s ‘Monster Study'”. Gretchen Reynolds, The New York Times, March 2003.

“The Real Lesson of the Stanford Prison Experiment” . Maria Konnikova, The New Yorker, June 2015.

“Gays tell of mutilation by apartheid army” . Chris McGreal, The Guardian, July 2000.

“Nuclear Savage: The Islands of Secret Project 4.1” . The Environment & Society Portal.

“Tuskegee Experiment: The Infamous Syphilis Study” . Elizabeth Nix, History.com, May 2017.

“The secret LSD-fuelled CIA experiment that inspired Stranger Things” . Richard Vine, The Guardian, August 2016.

“Guatemala victims of US syphilis study still haunted by the ‘devil’s experiment'” . Rory Carroll, The Guardian, June 2011.

“Nazi Medical Experiments” . The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Advertisement

10 Outrageous Experiments Conducted on Humans

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

Prisoners, the disabled, the physically and mentally sick, the poor -- these are all groups once considered fair game to use as subjects in your research experiments. And if you didn't want to get permission, you didn't have to, and many doctors and researchers conducted their experiments on people who were unwilling to participate or who were unknowingly participating.

Forty years ago the U.S. Congress changed the rules; informed consent is now required for any government-funded medical study involving human subjects. But before 1974 the ethics involved in using humans in research experiments was a little, let's say, loose. And the exploitation and abuse of human subjects was often alarming. We begin our list with one of the most famous instances of exploitation, a study that eventually helped change the public view about the lack of consent in the name of scientific advancements.

- Tuskegee Syphilis Study

- The Nazi Medical Experiments

- Watson's 'Little Albert' Experiment

- The Monster Study of 1939

- Stateville Penitentiary Malaria Study

- The Aversion Project in South Africa

- Milgram Shock Experiments

- CIA Mind-Control Experiments (Project MK-Ultra)

- The Human Vivisections of Herophilus

10: Tuskegee Syphilis Study

Syphilis was a major public health problem in the 1920s, and in 1928 the Julius Rosenwald Fund, a charity organization, launched a public healthcare project for blacks in the American rural south. Sounds good, right? It was, until the Great Depression rocked the U.S. in 1929 and the project lost its funding. Changes were made to the program; instead of treating health problems in underserved areas, in 1932 poor black men living in Macon County, Alabama, were instead enrolled in a program to treat what they were told was their "bad blood" (a term that, at the time, was used in reference to everything from anemia to fatigue to syphilis). They were given free medical care, as well as food and other amenities such as burial insurance, for participating in the study. But they didn't know it was all a sham. The men in the study weren't told that they were recruited for the program because they were actually suffering from the sexually transmitted disease syphilis, nor were they told they were taking part in a government experiment studying untreated syphilis, the "Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male." That's right: untreated.

Despite thinking they were receiving medical care, subjects were never actually properly treated for the disease. This went on even after penicillin hit the scene and became the go-to treatment for the infection in 1945, and after Rapid Treatment Centers were established in 1947. Despite concerns raised about the ethics of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study as early as 1936, the study didn't actually end until 1972 after the media reported on the multi-decade experiment and there was subsequent public outrage.

9: The Nazi Medical Experiments

During WWII, the Nazis performed medical experiments on adults and children imprisoned in the Dachau, Auschwitz, Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen concentration camps. The accounts of abuse, mutilation, starvation, and torture reads like a grisly compilation of all nine circles of hell. Prisoners in these death camps were subjected to heinous crimes under the guise of military advancement, medical and pharmaceutical advancement, and racial and population advancement.

Jews were subjected to experiments intended to benefit the military, including hypothermia studies where prisoners were immersed in ice water in an effort to ascertain how long a downed pilot could survive in similar conditions. Some victims were only allowed sea water, a study of how long pilots could survive at sea; these subjects, not surprisingly, died of dehydration. Victims were also exposed to high altitude in decompression chambers -- often followed with brain dissection on the living -- to study high-altitude sickness and how pilots would be affected by atmospheric pressure changes.

Effectively treating war injuries was also a concern for the Nazis, and pharmaceutical testing went on in these camps. Sulfanilamide was tested as a new treatment for war wounds. Victims were inflicted with wounds that were then intentionally infected. Infections and poisonings were also studied on human subjects. Tuberculosis (TB) was injected into prisoners in an effort to better understand how to immunize against the infection. Experiments with poison, to determine how fast subjects would die, were also on the agenda.

The Nazis also performed genetic and racially-motivated sterilizations, artificial inseminations, and also conducted experiments on twins and people of short stature.

8: Watson's 'Little Albert' Experiment

In 1920 John Watson, along with graduate student Rosalie Rayner, conducted an emotional-conditioning experiment on a nine-month-old baby -- whom they nicknamed "Albert B" -- at Johns Hopkins University in an effort to prove their theory that we're all born as blank slates that can be shaped. The child's mother, a wet nurse who worked at the hospital, was paid one dollar for allowing her son to take part.

The "Little Albert" experiment went like this: Researchers first introduced the baby to a small, furry white rat, of which he initially had no fear . (According to reports, he didn't really show much interest at all). Then they re-introduced him to the rat while a loud sound rang out. Over and over, "Albert" was exposed to the rat and startling noises until he became frightened any time he saw any small, furry animal (rats, for sure, but also dogs and monkeys) regardless of noise.

Who exactly "Albert" was remained unknown until 2010, when his identity was revealed to be Douglas Merritte. Merritte, it turns out, wasn't a healthy subject: He showed signs of behavioral and neurological impairment, never learned to talk or walk, and only lived to age six, dying from hydrocephalus (water on the brain). He also suffered from a bacterial meningitis infection he may have acquired accidentally during treatments for his hydrocephalus, or, as some theorize, may have been -- horrifyingly -- intentionally infected as part of another experiment.

In the end, Merritte was never deconditioned, and because he died at such a young age no one knows if he continued to fear small furry things post-experiment.

7: The Monster Study of 1939

Today we understand that stuttering has many possible causes. It may run in some families, an inherited genetic quirk of the language center of the brain. It may also occur because of a brain injury, including stroke or other trauma. Some young children stutter when they're learning to talk, but outgrow the problem. In some rare instances, it may be a side effect of emotional trauma. But you know what it's not caused by? Criticism.

In 1939 Mary Tudor, a graduate student at the University of Iowa, and her faculty advisor, speech expert Wendell Johnson, set out to prove stuttering could be taught through negative reinforcement -- that it's learned behavior. Over four months, 22 orphaned children were told they would be receiving speech therapy, but in reality they became subjects in a stuttering experiment; only about half were actually stutterers, and none received speech therapy.

During the experiment the children were split into four groups:

- Half of the stutterers were given negative feedback.

- The other half of stutterers were given positive feedback.

- Half of the non-stuttering group were all told they were beginning to stutterer and were criticized.

- The other half of non-stutterers were praised.

The only significant impact the experiment had was on that third group; these kids, despite never actually developing a stutter, began to change their behavior, exhibiting low self-esteem and adopting the self-conscious behaviors associated with stutterers. And those who did stutter didn't cease doing so regardless of the feedback they received.

6: Stateville Penitentiary Malaria Study

It's estimated that between 60 to 65 percent of American soldiers stationed in the South Pacific during WWII suffered from a malarial infection at some point during their service. For some units the infection proved to be more deadly than the enemy forces were, so finding an effective treatment was a high priority [source: Army Heritage Center Foundation]. Safe anti-malarial drugs were seen as essential to winning the war.

Beginning in 1944 and spanning over the course of two years, more than 400 prisoners at the Stateville Penitentiary in Illinois were subjects in an experiment aimed at finding an effective drug against malaria . Prisoners taking part in the experiment were infected with malaria, and then treated with experimental anti-malarial treatments. The experiment didn't have a hidden agenda, and its unethical methodology didn't seem to bother the American public, who were united in winning WWII and eager to bring the troops home — safe and healthy. The intent of the experiments wasn't hidden from the subjects, who were at the time praised for their patriotism and in many instances given shorter prison sentences in return for their participation.

5: The Aversion Project in South Africa

If you were living during the apartheid era in South Africa, you lived under state-regulated racial segregation. If that itself wasn't difficult enough, the state also controlled your sexuality.

The South African government upheld strict anti-homosexual laws. If you were gay you were considered a deviant — and your homosexuality was also considered a disease that could be treated. Even after homosexuality ceased to be considered a mental illness and aversion therapy as a way to cure it debunked, psychiatrists and Army medical professionals in the South African Defense Force (SADF) continued to believe the outdated theories and treatments. In particular, aversion therapy techniques were used on prisoners and on South Africans who were forced to join the military under the conscription laws of the time.

At Ward 22 at 1 Military hospital in Voortrekkerhoogte, Pretoria, between 1969 and 1987 attempts were made to "cure" perceived deviants. Homosexuals, gay men and lesbians were drugged and subjected to electroconvulsive behavior therapy while shown aversion stimuli (same-sex erotic photos), followed by erotic photos of the opposite sex after the electric shock. When the technique didn't work (and it absolutely didn't), victims were then treated with hormone therapy, which in some cases included chemical castration. In addition, an estimated 900 men and women also underwent gender reassignment surgery when subsequent efforts to "reorient" them failed — most without consent, and some left unfinished [source: Kaplan ].

4: Milgram Shock Experiments

Ghostbuster Peter Venkman, who is seen in the fictional film conducting ESP/electro-shock experiments on college students, was likely inspired by social psychologist Stanley Milgram's famous series of shock experiments conducted in the early 1960s. During Milgram's experiments "teachers" — Americans recruited for a Yale study they thought was about memory and learning — were told to read lists of words to "learners" (actors, although the teachers didn't know that). Each person in the teacher role was instructed to press a lever that would deliver a shock to their "learner" every time he made a mistake on word-matching quizzes. Teachers believed the voltage of shocks increased with each mistake, and ranged from 15 to 450 possible volts; roughly two-thirds of teachers shocked learners to the highest voltage , continuing to deliver jolts at the instruction of the experimenter.

In reality, this wasn't an experiment about memory and learning; rather, it was about how obedient we are to authority. No shocks were actually given.

Today, Milgram's shock experiments continue to be controversial; while they're criticized for their lack of realism, others point to the results as important to how humans behave when under duress. In 2010 the results of Milgram's study were repeated — with about 70 percent of teachers obediently administering what they believed to be the highest voltage shocks to their learners.

3: CIA Mind-Control Experiments (Project MK-Ultra)

If you're familiar with "Men Who Stare at Goats" or "The Manchurian Candidate" then you know: There was a period in the CIA's history when they performed covert mind-control experiments. If you thought it was fiction, it wasn't.

During the Cold War the CIA started researching ways they could turn Americans into CIA-controlled "superagents," people who could carry out assassinations and who wouldn't be affected by enemy interrogations. Under what was known as the MK-ULTRA project, CIA researchers experimented on unsuspecting American (and Canadian) citizens by slipping them psychedelic drugs, including LSD , PCP and barbiturates, as well as additional — and additionally illegal — methods such as hypnosis, and, possibly, chemical, biological, and radiological agents. Universities participated, mostly as a delivery system, also without their knowledge. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs estimates 7,000 soldiers were also involved in the research, without their consent.

The project endured for more than 20 years, during which the agency spent about $20 million. There was one death tied to the project, although more were suspected; tin 1973 the CIA destroyed what records were kept.

2: Unit 731

Using biological warfare was banned by the Geneva Protocol in 1925, but Japan rejected the ban. If germ warfare was effective enough to be banned, it must work, military leaders believed. Unit 731 , a secret unit in a secret facility — publicly known as the Epidemic Prevention and Water Supply Unit — was established in Japanese-controlled Manchuria, where by the mid-1930s Japan began experimenting with pathogenic and chemical warfare and testing on human subjects. There, military physicians and officers intentionally exposed victims to infectious diseases including anthrax , bubonic plague, cholera, syphilis, typhus and other pathogens, in an effort to understand how they affected the body and how they could be used in bombs and attacks in WWII.

In addition to working with pathogens, Unit 731 conducted experiments on people, including — but certainly not limited to — dissections and vivisections on living humans, all without anesthesia (the experimenters believed using it would skew the results of the research).

Many of the subjects were Chinese civilians and prisoners of war, but also included Russian and American victims among others — basically, anyone who wasn't Japanese was a potential subject. Today it's estimated that about 100,000 people were victims within the facility, but when you include the germ warfare field experiments (such as reports of Japanese planes dropping plague-infected fleas over Chinese villages and poisoning wells with cholera) the death toll climbs to estimates closer to 250,000, maybe more.

Believe it or not, after WWII the U.S. granted immunity to those involved in these war crimes committed at Unit 731 as part of an information exchange agreement — and until the 1980s, the Japanese government refused to admit any of this even happened.

1: The Human Vivisections of Herophilus

Ancient physician Herophilus is considered the father of anatomy. And while he made significant discoveries during his practice, it's how he learned about internal workings of the human body that lands him on this list.

Herophilus practiced medicine in Alexandria, Egypt, and during the reign of the first two Ptolemaio Pharoahs was allowed, at least for about 30 to 40 years, to dissect human bodies, which he did, publicly, along with contemporary Greek physician and anatomist Erasistratus. Under Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II, criminals could be sentenced to dissection and vivisection as punishment, and it's said the father of anatomy not only dissected the dead but also performed vivisection on an estimated 600 living prisoners [source: Elhadi ].

Herophilus made great strides in the study of human anatomy — especially the brain , eyes, liver, circulatory system, nervous system and reproductive system, during a time in history when dissecting human cadavers was considered an act of desecration of the body (there were no autopsies conducted on the dead, although mummification was popular in Egypt at the time). And, like today, performing vivisection on living bodies was considered butchery.

Frequently Asked Questions

How have these experiments influenced current ethical standards in research, what protections are in place today to prevent similar unethical research on humans, lots more information, author's note.

There is no denying that involving living, breathing humans in medical studies have produced some invaluable results, but there's that one medical saying most of us know, even if we're not in a medical field: first do no harm (or, if you're fancy, primum non nocere).

Related Articles

- What will medicine consider unethical in 100 years?

- How Human Experimentation Works

- Top 5 Crazy Government Experiments

- 10 Cover-ups That Just Made Things Worse

- 10 Really Smart People Who Did Really Dumb Things

- How Scientific Peer Review Works

More Great Links

- Journal of Clinical Investigation, 1948: "Procedures Used at Stateville Penitentiary for the Testing of Potential Antimalarial Agents"

- Stanley Milgram: "Behavioral Study of Obedience"

- Alving, Alf S. "Procedures Used At Stateville Penitentiary For The Testing Of Potential Antimalarial Agents." Journal of Clinical Investigation. Vol. 27, No. 3 (part 2). Pages 2-5. May 1948. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.jci.org/articles/view/101956

- American Heritage Center Foundation. "Education Materials Index: Malaria in World War II." (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.armyheritage.org/education-and-programs/educational-resources/education-materials-index/50-information/soldier-stories/182-malaria-in-world-war-ii

- Bartlett, Tom. "A New Twist in the Sad Saga of Little Albert." The Chronicle of Higher Education." Jan. 25, 2012. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://chronicle.com/blogs/percolator/a-new-twist-in-the-sad-saga-of-little-albert/28423

- Blass, Thomas. "The Man Who Shocked The World." Psychology Today. June 13, 2012. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/200203/the-man-who-shocked-the-world

- Brick, Neil. "Mind Control Documents & Links." Stop Mind Control and Ritual Abuse Today (S.M.A.R.T.). (Aug. 10, 2014) https://ritualabuse.us/mindcontrol/mc-documents-links/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee: The Tuskegee Timeline." Dec. 10, 2013. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm

- Cohen, Baruch. "The Ethics Of Using Medical Data From Nazi Experiments." Jlaw.com - Jewish Law Blog.(Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.jlaw.com/Articles/NaziMedEx.html

- Collins, Dan. "'Monster Study' Still Stings." CBS News. Aug. 6, 2003. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.cbsnews.com/news/monster-study-still-stings/

- Comfort, Nathaniel. "The prisoner as model organism: malaria research at Stateville Penitentiary." Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences." Vol. 40, no. 3. Pages 190-203. September 2009. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2789481/

- DeAngelis, T. "'Little Albert' regains his identity." Monitor on Psychology. Vol. 41, no. Page 10. 2010. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.apa.org/monitor/2010/01/little-albert.aspx

- Elhadi, Ali M. "The Journey of Discovering Skull Base Anatomy in Ancient Egypt and the Special Influence of Alexandria." Neurosurgical Focus. Vol. 33, No. 2. 2012. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/769263_5

- Fridlund, Alan J. "Little Albert: A neurologically impaired child." History of Psychology. Vol. 15, No. 4. Pages 302-327. November 2013. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/2012-01974-001/

- Harcourt, Bernard E. "Making Willing Bodies: Manufacturing Consent Among Prisoners and Soldiers, Creating Human Subjects, Patriots, and Everyday Citizens - The University of Chicago Malaria Experiments on Prisoners at Stateville Penitentiary." University of Chicago Law & Economics, Olin Working Paper No. 544; Public Law Working Paper No. 341. Feb. 6, 2011. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1758829

- Harris, Sheldon H. "Biological Experiments." Crimes of War Project. 2011. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.crimesofwar.org/a-z-guide/biological-experiments/

- Hornblum, Allen M. "They Were Cheap and Available: Prisoners as Research Subjects in Twentieth Century America." British Medical Journal. Vol. 315. Pages 1437-1441. 1997. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://gme.kaiserpapers.org/they-were-cheap-and-available.html

- Kaplan, Robert. "The Aversion Project -- Psychiatric Abuses In The South African Defence Force During The Apartheid Era." South African Medical Journal. Vol. 91, no. 3. Pages 216-217. March 2001. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://archive.samj.org.za/2001%20VOL%2091%20Jan-Dec/Articles/03%20March/1.5%20THE%20AVERSION%20PROJECT%20-%20PSYCHIATRIC%20ABUSES%20IN%20THE%20SOUTH%20AFRICAN%20DEFENCE%20FORCE%20DURING%20THE%20APART.pdf

- Kaplan, Robert M. "Treatment of homosexuality during apartheid." British Medical Journal. Vol. 329, no. 7480. Pages 1415-1416. Dec. 18, 2004. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC535952/

- Kaplan, Robert M. "Treatment of homosexuality in the South African Defence Force during the Apartheid years ." British Medical Journal. February 20, 2004. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.bmj.com/rapid-response/2011/10/30/treatment-homosexuality-south-african-defence-force-during-apartheid-years

- Keen, Judy. "Legal battle ends over stuttering experiment." USA Today. Aug. 27, 2007. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-08-26-stuttering_N.htm

- Kristof, Nicholas D. "Unmasking Horror -- A special report; Japan Confronting Gruesome War Atrocity." The New York Times. March 17, 1995. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.nytimes.com/1995/03/17/world/unmasking-horror-a-special-report-japan-confronting-gruesome-war-atrocity.html

- Landau, Elizabeth. "Studies show 'dark chapter' of medical research." CNN. Oct. 1, 2010. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.cnn.com/2010/HEALTH/10/01/guatemala.syphilis.tuskegee/

- Mayo Clinic. "Stuttering: Causes." Sept. 8, 2011. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/stuttering/basics/causes/con-20032854

- Mayo Clinic. "Syphilis." Jan. 2, 2014. (Aug. 20, 2014) http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/syphilis/basics/definition/con-20021862

- McCurry, Justin. "Japan unearths site linked to human experiments." The Guardian. Feb. 21, 2011. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/feb/21/japan-excavates-site-human-experiments

- McGreal, Chris. "Gays tell of mutilation by apartheid army." The Guardian. July 28, 2000. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.theguardian.com/world/2000/jul/29/chrismcgreal

- Milgram, Stanley. "Behavioral Study of Obedience." Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. No. 67. Pages 371-378. 1963. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://wadsworth.cengage.com/psychology_d/templates/student_resources/0155060678_rathus/ps/ps01.html

- NPR. "Taking A Closer Look At Milgram's Shocking Obedience Study." Aug. 28, 2013. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.npr.org/2013/08/28/209559002/taking-a-closer-look-at-milgrams-shocking-obedience-study

- Rawlings, Nate. "Top 10 Weird Government Secrets: CIA Mind-Control Experiments." Time. Aug. 6, 2010. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2008962_2008964_2008992,00.html

- Reynolds, Gretchen. "The Stuttering Doctor's 'Monster Study'." The New York Times. March 16, 2003. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.nytimes.com/2003/03/16/magazine/the-stuttering-doctor-s-monster-study.html

- Ryall, Julian. "Human bones could reveal truth of Japan's 'Unit 731' experiments." The Telegraph. Feb. 15, 2010. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/japan/7236099/Human-bones-could-reveal-truth-of-Japans-Unit-731-experiments.html

- Science Channel - Dark Matters. "Project MKULTRA." (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.sciencechannel.com/tv-shows/dark-matters-twisted-but-true/documents/project-mkultra.htm

- Shea, Christopher. "Stanley Milgram and the uncertainty of evil." The Boston Globe. Sept. 29, 2013. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2013/09/28/stanley-milgram-and-uncertainty-evil/qUjame9xApiKc6evtgQRqN/story.html

- Shermer, Michael. "What Milgram's Shock Experiments Really Mean." Scientific American. Oct. 16, 2012. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-milgrams-shock-experiments-really-mean/

- Si-Yang Bay, Noel. "Green anatomist herohilus: the father of anatomy." Anatomy & Cell Biology. Vol. 43, No. 4. Pages 280-283. December 2010. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3026179/

- Stobbe, Mike. "Ugly past of U.S. human experiments uncovered." NBC News. Feb. 27, 2011. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.nbcnews.com/id/41811750/ns/health-health_care/t/ugly-past-us-human-experiments-uncovered

- Tuskegee University. "About the USPHS Syphilis Study." (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.tuskegee.edu/about_us/centers_of_excellence/bioethics_center/about_the_usphs_syphilis_study.aspx

- Tyson, Peter. "Holocaust on Trial: The Experiments." PBS. October 2000. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/holocaust/experiside.html

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. "Nazi Medical Experiments." June 20, 2014. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005168

- Van Zul, Mikki. "The Aversion Project." South African medical Research Council. October 1999. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.mrc.ac.za/healthsystems/aversion.pdf

- Watson, John B.; and Rosalie Rayner. "Conditioned Emotional Reactions." Journal of Experimental Psychology. Vol. 3, No. 1. Pages 1-14. 1920. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Watson/emotion.htm

- Wiltse, LL. "Herophilus of Alexandria (325-255 B.C.). The father of anatomy." Spine. Vol. 23, no. 7. Pages 1904-1914. Sept. 1, 1998. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9762750

- Working, Russell. "The trial of Unit 731." June 2001. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2001/06/05/commentary/world-commentary/the-trial-of-unit-731/

- Zetter, Kim. "April 13, 1953: CIA OKs MK-ULTRA Mind-Control Tests." Wired. April 13, 2010. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.wired.com/2010/04/0413mk-ultra-authorized/

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

- 20 Most Unethical Experiments in Psychology

Humanity often pays a high price for progress and understanding — at least, that seems to be the case in many famous psychological experiments. Human experimentation is a very interesting topic in the world of human psychology. While some famous experiments in psychology have left test subjects temporarily distressed, others have left their participants with life-long psychological issues . In either case, it’s easy to ask the question: “What’s ethical when it comes to science?” Then there are the experiments that involve children, animals, and test subjects who are unaware they’re being experimented on. How far is too far, if the result means a better understanding of the human mind and behavior ? We think we’ve found 20 answers to that question with our list of the most unethical experiments in psychology .

Emma Eckstein

Electroshock Therapy on Children

Operation Midnight Climax

The Monster Study

Project MKUltra

The Aversion Project

Unnecessary Sexual Reassignment

Stanford Prison Experiment

Milgram Experiment

The Monkey Drug Trials

Featured Programs

Facial expressions experiment.

Little Albert

Bobo Doll Experiment

The Pit of Despair

The Bystander Effect

Learned Helplessness Experiment

Racism Among Elementary School Students

UCLA Schizophrenia Experiments

The Good Samaritan Experiment

Robbers Cave Experiment

Related Resources:

- What Careers are in Experimental Psychology?

- What is Experimental Psychology?

- The 25 Most Influential Psychological Experiments in History

- 5 Best Online Ph.D. Marriage and Family Counseling Programs

- Top 5 Online Doctorate in Educational Psychology

- 5 Best Online Ph.D. in Industrial and Organizational Psychology Programs

- Top 10 Online Master’s in Forensic Psychology

- 10 Most Affordable Counseling Psychology Online Programs

- 10 Most Affordable Online Industrial Organizational Psychology Programs

- 10 Most Affordable Online Developmental Psychology Online Programs

- 15 Most Affordable Online Sport Psychology Programs

- 10 Most Affordable School Psychology Online Degree Programs

- Top 50 Online Psychology Master’s Degree Programs

- Top 25 Online Master’s in Educational Psychology

- Top 25 Online Master’s in Industrial/Organizational Psychology

- Top 10 Most Affordable Online Master’s in Clinical Psychology Degree Programs

- Top 6 Most Affordable Online PhD/PsyD Programs in Clinical Psychology

- 50 Great Small Colleges for a Bachelor’s in Psychology

- 50 Most Innovative University Psychology Departments

- The 30 Most Influential Cognitive Psychologists Alive Today

- Top 30 Affordable Online Psychology Degree Programs

- 30 Most Influential Neuroscientists

- Top 40 Websites for Psychology Students and Professionals

- Top 30 Psychology Blogs

- 25 Celebrities With Animal Phobias

- Your Phobias Illustrated (Infographic)

- 15 Inspiring TED Talks on Overcoming Challenges

- 10 Fascinating Facts About the Psychology of Color

- 15 Scariest Mental Disorders of All Time

- 15 Things to Know About Mental Disorders in Animals

- 13 Most Deranged Serial Killers of All Time

Site Information

- About Online Psychology Degree Guide

- Culture & Trends

- Share & Save —

- Decision 2024

- Investigations

- Tech & Media

- Video Features

- NBC Asian America

- Los Angeles

- Dallas-Fort Worth

- Philadelphia

- Washington, D.C.

- South Florida

- Connecticut

- Nightly News

- Meet the Press

- NBC News Now

- Nightly Films

- Special Features

- Newsletters

More From NBC

- NBCU Academy

- NEXT STEPS FOR VETS

- NBC News Site Map

Follow NBC News

news Alerts

There are no new alerts at this time

- Latest Stories

Ugly past of U.S. human experiments uncovered

Shocking as it may seem, U.S. government doctors once thought it was fine to experiment on disabled people and prison inmates. Such experiments included giving hepatitis to mental patients in Connecticut, squirting a pandemic flu virus up the noses of prisoners in Maryland, and injecting cancer cells into chronically ill people at a New York hospital.

Much of this horrific history is 40 to 80 years old, but it is the backdrop for a meeting in Washington this week by a presidential bioethics commission. The meeting was triggered by the government's apology last fall for federal doctors infecting prisoners and mental patients in Guatemala with syphilis 65 years ago.

U.S. officials also acknowledged there had been dozens of similar experiments in the United States — studies that often involved making healthy people sick.

An exhaustive review by The Associated Press of medical journal reports and decades-old press clippings found more than 40 such studies. At best, these were a search for lifesaving treatments; at worst, some amounted to curiosity-satisfying experiments that hurt people but provided no useful results.

Inevitably, they will be compared to the well-known Tuskegee syphilis study. In that episode, U.S. health officials tracked 600 black men in Alabama who already had syphilis but didn't give them adequate treatment even after penicillin became available.

These studies were worse in at least one respect — they violated the concept of "first do no harm," a fundamental medical principle that stretches back centuries.

"When you give somebody a disease — even by the standards of their time — you really cross the key ethical norm of the profession," said Arthur Caplan, director of the University of Pennsylvania's Center for Bioethics.

Attitude similar to Nazi experiments Some of these studies, mostly from the 1940s to the '60s, apparently were never covered by news media. Others were reported at the time, but the focus was on the promise of enduring new cures, while glossing over how test subjects were treated.

Attitudes about medical research were different then. Infectious diseases killed many more people years ago, and doctors worked urgently to invent and test cures. Many prominent researchers felt it was legitimate to experiment on people who did not have full rights in society — people like prisoners, mental patients, poor blacks. It was an attitude in some ways similar to that of Nazi doctors experimenting on Jews.

"There was definitely a sense — that we don't have today — that sacrifice for the nation was important," said Laura Stark, a Wesleyan University assistant professor of science in society, who is writing a book about past federal medical experiments.

The AP review of past research found:

- A federally funded study begun in 1942 injected experimental flu vaccine in male patients at a state insane asylum in Ypsilanti, Mich., then exposed them to flu several months later. It was co-authored by Dr. Jonas Salk, who a decade later would become famous as inventor of the polio vaccine.

Some of the men weren't able to describe their symptoms, raising serious questions about how well they understood what was being done to them. One newspaper account mentioned the test subjects were "senile and debilitated." Then it quickly moved on to the promising results.

- In federally funded studies in the 1940s, noted researcher Dr. W. Paul Havens Jr. exposed men to hepatitis in a series of experiments, including one using patients from mental institutions in Middletown and Norwich, Conn. Havens, a World Health Organization expert on viral diseases, was one of the first scientists to differentiate types of hepatitis and their causes.

A search of various news archives found no mention of the mental patients study, which made eight healthy men ill but broke no new ground in understanding the disease.

- Researchers in the mid-1940s studied the transmission of a deadly stomach bug by having young men swallow unfiltered stool suspension. The study was conducted at the New York State Vocational Institution, a reformatory prison in West Coxsackie. The point was to see how well the disease spread that way as compared to spraying the germs and having test subjects breathe it. Swallowing it was a more effective way to spread the disease, the researchers concluded. The study doesn't explain if the men were rewarded for this awful task.

- A University of Minnesota study in the late 1940s injected 11 public service employee volunteers with malaria, then starved them for five days. Some were also subjected to hard labor, and those men lost an average of 14 pounds. They were treated for malarial fevers with quinine sulfate. One of the authors was Ancel Keys, a noted dietary scientist who developed K-rations for the military and the Mediterranean diet for the public. But a search of various news archives found no mention of the study.

- For a study in 1957, when the Asian flu pandemic was spreading, federal researchers sprayed the virus in the noses of 23 inmates at Patuxent prison in Jessup, Md., to compare their reactions to those of 32 virus-exposed inmates who had been given a new vaccine.

- Government researchers in the 1950s tried to infect about two dozen volunteering prison inmates with gonorrhea using two different methods in an experiment at a federal penitentiary in Atlanta. The bacteria was pumped directly into the urinary tract through the penis, according to their paper.

The men quickly developed the disease, but the researchers noted this method wasn't comparable to how men normally got infected — by having sex with an infected partner. The men were later treated with antibiotics. The study was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, but there was no mention of it in various news archives.

Though people in the studies were usually described as volunteers, historians and ethicists have questioned how well these people understood what was to be done to them and why, or whether they were coerced.

Victims for science Prisoners have long been victimized for the sake of science. In 1915, the U.S. government's Dr. Joseph Goldberger — today remembered as a public health hero — recruited Mississippi inmates to go on special rations to prove his theory that the painful illness pellagra was caused by a dietary deficiency. (The men were offered pardons for their participation.)

But studies using prisoners were uncommon in the first few decades of the 20th century, and usually performed by researchers considered eccentric even by the standards of the day. One was Dr. L.L. Stanley, resident physician at San Quentin prison in California, who around 1920 attempted to treat older, "devitalized men" by implanting in them testicles from livestock and from recently executed convicts.

Newspapers wrote about Stanley's experiments, but the lack of outrage is striking.

"Enter San Quentin penitentiary in the role of the Fountain of Youth — an institution where the years are made to roll back for men of failing mentality and vitality and where the spring is restored to the step, wit to the brain, vigor to the muscles and ambition to the spirit. All this has been done, is being done ... by a surgeon with a scalpel," began one rosy report published in November 1919 in The Washington Post.

Around the time of World War II, prisoners were enlisted to help the war effort by taking part in studies that could help the troops. For example, a series of malaria studies at Stateville Penitentiary in Illinois and two other prisons was designed to test antimalarial drugs that could help soldiers fighting in the Pacific.

It was at about this time that prosecution of Nazi doctors in 1947 led to the "Nuremberg Code," a set of international rules to protect human test subjects. Many U.S. doctors essentially ignored them, arguing that they applied to Nazi atrocities — not to American medicine.

The late 1940s and 1950s saw huge growth in the U.S. pharmaceutical and health care industries, accompanied by a boom in prisoner experiments funded by both the government and corporations. By the 1960s, at least half the states allowed prisoners to be used as medical guinea pigs.

But two studies in the 1960s proved to be turning points in the public's attitude toward the way test subjects were treated.

The first came to light in 1963. Researchers injected cancer cells into 19 old and debilitated patients at a Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in the New York borough of Brooklyn to see if their bodies would reject them.

The hospital director said the patients were not told they were being injected with cancer cells because there was no need — the cells were deemed harmless. But the experiment upset a lawyer named William Hyman who sat on the hospital's board of directors. The state investigated, and the hospital ultimately said any such experiments would require the patient's written consent.

At nearby Staten Island, from 1963 to 1966, a controversial medical study was conducted at the Willowbrook State School for children with mental retardation. The children were intentionally given hepatitis orally and by injection to see if they could then be cured with gamma globulin.

Those two studies — along with the Tuskegee experiment revealed in 1972 — proved to be a "holy trinity" that sparked extensive and critical media coverage and public disgust, said Susan Reverby, the Wellesley College historian who first discovered records of the syphilis study in Guatemala.

'My back is on fire!' By the early 1970s, even experiments involving prisoners were considered scandalous. In widely covered congressional hearings in 1973, pharmaceutical industry officials acknowledged they were using prisoners for testing because they were cheaper than chimpanzees.

Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia made extensive use of inmates for medical experiments. Some of the victims are still around to talk about it. Edward "Yusef" Anthony, featured in a book about the studies, says he agreed to have a layer of skin peeled off his back, which was coated with searing chemicals to test a drug. He did that for money to buy cigarettes in prison.

"I said 'Oh my God, my back is on fire! Take this ... off me!'" Anthony said in an interview with The Associated Press, as he recalled the beginning of weeks of intense itching and agonizing pain.

The government responded with reforms. Among them: The U.S. Bureau of Prisons in the mid-1970s effectively excluded all research by drug companies and other outside agencies within federal prisons.

As the supply of prisoners and mental patients dried up, researchers looked to other countries.

It made sense. Clinical trials could be done more cheaply and with fewer rules. And it was easy to find patients who were taking no medication, a factor that can complicate tests of other drugs.

Additional sets of ethical guidelines have been enacted, and few believe that another Guatemala study could happen today. "It's not that we're out infecting anybody with things," Caplan said.

Still, in the last 15 years, two international studies sparked outrage.

One was likened to Tuskegee. U.S.-funded doctors failed to give the AIDS drug AZT to all the HIV-infected pregnant women in a study in Uganda even though it would have protected their newborns. U.S. health officials argued the study would answer questions about AZT's use in the developing world.

The other study, by Pfizer Inc., gave an antibiotic named Trovan to children with meningitis in Nigeria, although there were doubts about its effectiveness for that disease. Critics blamed the experiment for the deaths of 11 children and the disabling of scores of others. Pfizer settled a lawsuit with Nigerian officials for $75 million but admitted no wrongdoing.

Last year, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' inspector general reported that between 40 and 65 percent of clinical studies of federally regulated medical products were done in other countries in 2008, and that proportion probably has grown. The report also noted that U.S. regulators inspected fewer than 1 percent of foreign clinical trial sites.

Monitoring research is complicated, and rules that are too rigid could slow new drug development. But it's often hard to get information on international trials, sometimes because of missing records and a paucity of audits, said Dr. Kevin Schulman, a Duke University professor of medicine who has written on the ethics of international studies.

Syphilis study These issues were still being debated when, last October, the Guatemala study came to light.

In the 1946-48 study, American scientists infected prisoners and patients in a mental hospital in Guatemala with syphilis, apparently to test whether penicillin could prevent some sexually transmitted disease. The study came up with no useful information and was hidden for decades.

Story: U.S. apologizes for Guatemala syphilis experiments

The Guatemala study nauseated ethicists on multiple levels. Beyond infecting patients with a terrible illness, it was clear that people in the study did not understand what was being done to them or were not able to give their consent. Indeed, though it happened at a time when scientists were quick to publish research that showed frank disinterest in the rights of study participants, this study was buried in file drawers.

"It was unusually unethical, even at the time," said Stark, the Wesleyan researcher.

"When the president was briefed on the details of the Guatemalan episode, one of his first questions was whether this sort of thing could still happen today," said Rick Weiss, a spokesman for the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

That it occurred overseas was an opening for the Obama administration to have the bioethics panel seek a new evaluation of international medical studies. The president also asked the Institute of Medicine to further probe the Guatemala study, but the IOM relinquished the assignment in November, after reporting its own conflict of interest: In the 1940s, five members of one of the IOM's sister organizations played prominent roles in federal syphilis research and had links to the Guatemala study.

So the bioethics commission gets both tasks. To focus on federally funded international studies, the commission has formed an international panel of about a dozen experts in ethics, science and clinical research. Regarding the look at the Guatemala study, the commission has hired 15 staff investigators and is working with additional historians and other consulting experts.

The panel is to send a report to Obama by September. Any further steps would be up to the administration.

Some experts say that given such a tight deadline, it would be a surprise if the commission produced substantive new information about past studies. "They face a really tough challenge," Caplan said.

- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

5 Unethical Medical Experiments Brought Out of the Shadows of History

Prisoners and other vulnerable populations often bore the brunt of unethical medical experimentation..

Most people are aware of some of the heinous medical experiments of the past that violated human rights. Participation in these studies was either forced or coerced under false pretenses. Some of the most notorious examples include the experiments by the Nazis, the Tuskegee syphilis study, the Stanford Prison Experiment, and the CIA’s LSD studies.

But there are many other lesser-known experiments on vulnerable populations that have flown under the radar. Study subjects often didn’t — or couldn’t — give consent. Sometimes they were lured into participating with a promise of improved health or a small amount of compensation. Other times, details about the experiment were disclosed but the extent of risks involved weren’t.

This perhaps isn’t surprising, as doctors who conducted these experiments were representative of prevailing attitudes at the time of their work. But unfortunately, even after informed consent was introduced in the 1950s , disregard for the rights of certain populations continued. Some of these researchers’ work did result in scientific advances — but they came at the expense of harmful and painful procedures on unknowing subjects.

Here are five medical experiments of the past that you probably haven’t heard about. They illustrate just how far the ethical and legal guidepost, which emphasizes respect for human dignity above all else, has moved.

The Prison Doctor Who Did Testicular Transplants

From 1913 to 1951, eugenicist Leo Stanley was the chief surgeon at San Quentin State Prison, California’s oldest correctional institution. After performing vasectomies on prisoners, whom he recruited through promises of improved health and vigor, Stanley turned his attention to the emerging field of endocrinology, which involves the study of certain glands and the hormones they regulate. He believed the effects of aging and decreased hormones contributed to criminality, weak morality, and poor physical attributes. Transplanting the testicles of younger men into those who were older would restore masculinity, he thought.

Stanley began by using the testicles of executed prisoners — but he ran into a supply shortage. He solved this by using the testicles of animals, including goats and deer. At first, he physically implanted the testicles directly into the inmates. But that had complications, so he switched to a new plan: He ground up the animal testicles into a paste, which he injected into prisoners’ abdomens. By the end of his time at San Quentin, Stanley did an estimated 10,000 testicular procedures .

The Oncologist Who Injected Cancer Cells Into Patients and Prisoners

During the 1950s and 1960s, Sloan-Kettering Institute oncologist Chester Southam conducted research to learn how people’s immune systems would react when exposed to cancer cells. In order to find out, he injected live HeLa cancer cells into patients, generally without their permission. When patient consent was given, details around the true nature of the experiment were often kept secret. Southam first experimented on terminally ill cancer patients, to whom he had easy access. The result of the injection was the growth of cancerous nodules , which led to metastasis in one person.

Next, Southam experimented on healthy subjects , which he felt would yield more accurate results. He recruited prisoners, and, perhaps not surprisingly, their healthier immune systems responded better than those of cancer patients. Eventually, Southam returned to infecting the sick and arranged to have patients at the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in Brooklyn, NY, injected with HeLa cells. But this time, there was resistance. Three doctors who were asked to participate in the experiment refused, resigned, and went public.