Career Progression in Clinical Research: Transitioning from a Clinical Research Coordinator to a Monitoring Clinical Research Associate (CRA)

Thomas Boothby, MS, CCRP CRA II, Boston Scientific

Abstract : Research coordinators may transition to clinical research associates/monitors during their careers. This article provides an overview of how to determine whether it is the right time to make this transition, how to evaluate current competencies and gaps that must be filled in order to make this transition, and how to address needs during the on-boarding process. A roadmap in the form of a checklist is provided to help make the transition from research coordinator to clinical research associate (CRA) a smooth one.

Disclosure: The author has a relevant financial relationship with respect to this article with Boston Scientific, where he is employed as a monitoring CRA.

Introduction

A research coordinator is a person at the clinical research site who is involved in the daily tasks of enrollment, data entry, and all other aspects of clinical trials at the site level. A clinical research associate (CRA), or monitor, is the individual who visits clinical research sites to review their medical records and do the standard monitoring visits. Before the author was a CRA, he was a research coordinator for fourteen years. This article describes how the author made the transition from clinical research coordinator to CRA/clinical research monitor and includes some suggestions for those looking to make a similar career change.

When to Transition from Research Coordinator to CRA

While people naturally want to progress their careers as fast as possible, it is important to only make thetransition from research coordinator to CRA when the time is right. The grass is not always greener on the other side of the work fence.

The author knew that he was ready to make the transition from research coordinator to CRA because he felt that he had mastered all the tasks of a research coordinator. His job became stagnant, and he was looking for something better. Fatigue in the current work environment is another reason for why individuals may be looking to make this transition. Of all members of the clinical research team, research coordinators have the most difficult job. In the author’s opinion, they are often overworked and underpaid, and their contributions to the overall study are sometimes overlooked. Other reasons to make the transition from research coordinator to CRA include potential career progression and the opportunity to try something new. Some individuals may find that the travel component that goes along with being a monitor is a positive as well.

There are five stages of change according to a behavioral change model: pre-contemplation, contemplation, determination, action, and maintenance. In the pre-contemplation phase, people are not thinking about transitioning yet or may have obstacles in their daily lives that are preventing them from exploring new opportunities. When people are becoming serious about change, they are in the determination or action phases. During these phases, research coordinators who want to transition to CRAs might apply for new positions or become certified clinical research professionals (SOCRA CCRP®) as they try to gain new skills for the job market. When considering a transition from research coordinator to CRA, it is important to identify one’s place in the behavioral change model.

Qualifications and Background of CRAs

When the author was applying for CRA positions in 2015, he always saw a requirement for at least two years of experience as a monitor. This requirement is often a barrier to those looking to make this career transition. In 2010, ClinicalTrials.gov listed more than 100,000 clinical studies. By 2019, that number has increased to more than 300,000 clinical studies. The clinical research market has exploded over the last decade. More people are needed to monitor and to run clinical studies now than ever before. While some companies are less likely to require two years of monitoring experience now due to a depleted pool of candidates, these same companies may be more open to supplemental forms of experience such as certifications, course work, and on-the-job experience.

Thus, this is a great time to act on the decision to transition from research coordinator to CRA. From 2014 to 2024, the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that CRA positions will increase 14% annually. This increase in the job market, coupled with the high level of CRA turnover, could lead to a very strong job market in the future. At Boston Scientific, turnover among CRAs is fairly low due to the strong structure and principles. Many CRAs within Boston Scientific have been with the company for 10 to 20 years or longer.

Table 1 highlights the typical background of CRAs. Most CRAs are current or former nurses who have experience as a research coordinator or a research assistant. Many universities now offer bachelor’s, master’s, and certificate programs in clinical research as another form of training for these research related roles. In Michigan, where the author is from, Eastern Michigan University has a two-year master’s degree program in clinical research. Like the author, CRAs can often be a former research coordinator.

When the author was transitioning from research coordinator to CRA, he got his foot in the door by working closely with a monitor who still works for Boston Scientific. Relationships between research coordinators and CRAs can be contentious due to the nature of monitoring. Research coordinators should treat monitors and sponsor staff well and with respect, and they should treat monitoring visits as a learning opportunity and not a criticism of the coordinator’s work. These relationships do not need to be contentious. A good working relationship with a clinical research site’s CRAs can serve as a potential audition for a monitoring position.

CRAs typically have a clinical research certification, either SOCRA’s certified clinical research professional (CCRP®) or the Association of Clinical Research Professionals-Certified Professional (ACRP-CP). Some companies provide tuition reimbursement for programs and certifications such as these as a way of employee enhancement. Research coordinators can participate in enrichment programs such as these and obtain certifications to help boost their resume and become more marketable to CROs and sponsors. When researching these programs, individuals must do their due diligence to ensure that the program or certification is offered by a legitimate organization and is accredited. Hiring managers know where to find the gold standards in clinical research programs and certifications, and those that do not fit this standard can even be viewed as a negative on ones resume.

The author is a SOCRA CCRP®, Certified Clinical Research Professional, which is an excellent indicator of knowledge for a monitoring position. The test includes knowledge of the regulations and the role of the monitor. There are also some CRO-development programs such as SOCRA’s Clinical Research Monitoring Conference and one-year certificate programs such as the Harvard Medical School global clinical scholar’s research training program.

Networking through the clinical research site’s CRAs and professional forums and groups such as SOCRA is a great way to find CRA positions and interact with other research professionals. At conferences, CROs often have booths in the exhibit hall where research coordinators can meet CRO staff, learn more about opportunities, and leave their resume with CRO staff.

A Typical Day in the Life of a CRA

The life of a CRA has its positives and negatives (Table 2). There are many things that the author wishes he knew before he became a monitor. The author works from home a great deal of the time. If he is not on the road visiting a clinical research site, he is working at home either preparing for a visit, writing follow-up visit letters, or performing other administrative work. Visit preparation and follow up is a crucial part of the home office work. CRAs have very strict compliance guidelines for completing monitoring visits and monitoring reports in a timely manner. Since recently becoming a lead CRA, the author has also been doing a great deal of administrative and compliance work with more of a global view of a clinical trial.

Some clinical research organizations (CROs) and sponsors have onsite monitors who can do remote visits and activities. Whether visits are onsite or remote, monitors are constantly in contact with clinical research sites to follow up on action items from monitoring visits or to answer protocol specific questions the site coordinators may have.

At most companies, about 60-80% of the monitor’s time is spent traveling to sites. The author currently covers all of Michigan, and he has covered other areas, including Wisconsin, New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. CRAs are often away for several days at a time depending on the current workload. This can be difficult on families and personal relationships. While the author travels extensively, there are some times when he travels more than others. Sometimes he does back-to-back visits and may be gone for several days at a time. After that, he may be home for several days. The extensive travel required of CRAs is a key consideration when exploring this career transition.

Being a CRA takes a great deal of self-discipline. Monitoring offers a flexible work arrangement, so monitors can work later in the day or take time off during the normal workday. However, if the CRA does not accomplish what he/she should accomplish, this will be glaringly obvious. Management and co-workers will immediately know if the CRA does not show up to meetings or has difficulty answering questions about his/her monitoring activities or their monitor role in general.

Starting a Monitoring Job

Boston Scientific has a rigorous onboarding process comprised of four to six months of training. After the author was hired as a CRA, he spent months learning the work instructions and going out on preceptor visits. In the beginning, the new CRA observes a senior CRA. Over time, the new CRA does more of the monitoring. By the end of the training, the new CRA is doing the monitoring visit, and the senior CRA is observing and making suggestions to the new hire on how the new hire can improve.

There are various levels of monitors at Boston Scientific: CRA I (for new hires), CRA II, and senior CRA. More experienced CRAs often mentor new CRAs. It is extremely helpful to find CRAs who can serve as mentors and answer questions.

CROs and sponsors have many systems that CRAs must learn. At Boston Scientific, these systems include electronic data capture, clinical trial management, auxiliary programs to help remote employees, and cloud-based filing systems. Being a CRA might be very difficult for people who are resistant to change or have difficulty with technology.

There are several types of monitoring (Table 3). The author would be considered a traditional CRA or monitor. By this, he does traditional onsite monitoring via annual or semi-annual visits to clinical research sites based upon the study’s monitoring plan. At smaller organizations, monitors may travel more often or may have an expanded territory to cover. It is important to ask how much travel is involved and how many monitors are on the team during the interview process. If a company has fewer monitors, more travel will be involved.

Many Boston Scientific protocols require annual monitoring visits. The author visits his clinical research sites at minimum once a year but generally 2-3 times per year. Some of the more difficult sites, high enrollers, and those that are more likely to be inspected by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration are monitored more often. Many sites are participating in more than one Boston Scientific study. For example, the author monitors a site in New York that is conducting several studies. He will monitor two studies during one visit. This saves him time and travel and saves the company money by reducing travel costs. Boston Scientific also uses a risk-based monitoring strategy.

In-house regulatory CRAs at Boston Scientific, called trial management CRAs, interact with the sites on regulatory matters, study startup, and study closure. They work primarily by email and lean on traditional CRAs such as the monitor to be the face of the company with the research coordinators and help ensure that tasks are completed on time. Many hospitals also run their own clinical studies and may have in-house monitors.

Boston Scientific does use remote monitoring in certain studies and circumstances. Remote monitoring takes a great deal of work and technological experience at both the sponsor and site level. It involves a great deal of scanning and correspondence by the research coordinators, which can take a lot of their time and resources.

Sponsor CRAs generally deal with one indication, while CRO CRAs can work on studies for different indications or therapies. In one month, for example, CRO CRAs may be doing four indications at four sites for four sponsors. This requires understanding a great deal of information and being able to use different systems. Good organization is key when working as a CRA, whether for a sponsor or a CRO.

Recently, the author progressed from a CRA II to a senior CRA. As a senior CRA, the author has a larger leadership role and is expected to participate more in training and mentoring other CRAs. Boston Scientific has some centralized monitoring that will look at certain metrics and internal documents to guide monitors in their daily monitoring activities. Monitors are closely linked to the trial managers who actually run the studies. They also deal with safety and data managers as well as their CRA manager and the director of operations. Boston Scientific recently created an associate clinical trial manager position as a way to slowly transition some staff members into clinical trial managers, and the author is also transitioning into this role.

One common drawback about this transition process from research coordinator to CRA is that a CRA is one step removed from patient care. Working directly with patients as a research coordinator is something that the author misses. It is important to remember that CRAs help protect patients who are participating in clinical studies at more of an indirect level. This ideology helps prevent burnout, especially when monitors are swamped with the many reports that are necessary as part of the monitoring process.

Checklist for Transitioning from Research Coordinator to CRA

Table 4 has a checklist for determining whether one is ready to make the transition from research coordinator to CRA. Prior to applying for positions, the research coordinator must consider his/her stage in the behavior change model. Unless the research coordinator is ready to transition to a CRA position, he/she should not do it. Becoming a CRA can be difficult without two to five years of research experience in medical devices, pharma, or academia in some capacity. A research coordinator who wants to transition to a CRA should work closely with current CRAs who can provide mentoring and networking opportunities as well as exploring other networking avenues such as SOCRA and ACRP forums, LinkedIn, and also attending the annual events or local events put on by these organizations.

It is important for research coordinators to bolster their resumes by completing supplemental training or certifications. Resumes should be up-to-date and attractive to potential employers. This means including details about accomplishments along with basic information such as job titles and education.

The research coordinator must also consider the travel demands of a CRA position, the types of monitoring to pursue, and his/her stage in the behavior change model. Travel is a major part of a CRA position and should be a focal point of your conversation with a hiring representative. Finally, the types of monitoring including central monitoring, remote monitoring, and regional monitoring should be considered.

Monitoring is a great job. It allows a lot of freedom. However, CRAs also have a great deal of responsibility. CRAs must be driven, willing to put in the time, and have the necessary work ethic while maintaining vigilance and holding others accountable for good clinical practices.

Typical Background of a CRA

- Nursing degree with a clinical research background

- Bachelor’s or master’s degree in clinical research

- Former/current research coordinator

- Clinical experience (medical assistant, registered nurse, or nurse practitioner)

- Clinical research certified ( SOCRA CCRP ® or ACRP-CP)

- Research experience/background

- Science/academic research background

The Life of a CRA

- This requires being self-motivated and driven

- Sometimes performing a combination of onsite and remote monitoring

- Email, etc.

- At times, CRAs are gone for several days at a time depending on current workload

- Visit preparation and follow-up is a crucial part of work at home

Types of Monitoring

- Annual or semi-annual visits based upon the monitoring plan

- Risk-based monitoring/central monitoring

- Remote monitoring

- In-house CRAs and regulatory CRAs

- Sponsor CRA/monitor

- CRO CRA/monitor

Checklist for Transitioning from a Clinical Research Coordinator

to a Monitoring CRA (Clinical Research Associate)

- 2-5 years of research experience as a research coordinator or research assistant

- Able to work with current CRAs as part of a mentorship or network with CRAs

- Completion of supplemental training or certifications to support career goals and bolster resume

- Explore networking avenues

- Up-to-date resume that is attractive to potential employers

- Able to meet travel demands of a CRA position

- Consideration of types of monitoring to pursue

- Stage in the behavior change model

7 thoughts on “Career Progression in Clinical Research: Transitioning from a Clinical Research Coordinator to a Monitoring Clinical Research Associate (CRA)”

Your articles are always helpful and I always get something new to learn from them.

Research Update Organization

you are always giving something new. thank you for that.

Very clear and helpful article! The tables listing the different types of monitoring roles and the items to consider whether this is right transition are a great summary, too.

- Pingback: An overview of a career in clinical research: What jobs are available in this field? - Rebiz Zield

This is a very clear and collective article. The tables are the best helpful tips and resources for anyone interested for career advancement in clinical research. I really appreciate the author’s time and effort to sharing this article.

- Pingback: Career Growth Opportunities in Clinical Research

- Pingback: Introduction to Clinical Research: What Every Student Should Know - Drug Safety and Pharmacovigilance Course

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

2024 ANNUAL CONFERENCE

ADVANCING INNOVATION AND INTEGRITY:

A TIME FOR TRANSFORMATION IN CLINICAL RESEARCH

8 tracks I 20+ Topic Areas I 100+ Sessions I 70+CE

Climbing the research ladder in industry

When I started writing about careers in industry, I didn't fully realize how many different job titles there would be. Even when just focusing on careers in research, the terminology can get confusing, and it can be hard to know what types of job titles to search for.

So, this week I’m breaking it down. The positions described below start at the most junior and move up the theoretical research hierarchical ladder. Keep in mind that most employees aren't climbing that ladder from bottom to top — there are many different entry points into industry that will greatly depend on your education and experience.

Also keep in mind that no two career paths are going to look the same. Biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies vary in scope and size, both of which can influence career trajectories and timelines. Plus, everyone is different, so their career trajectories will reflect that. Try not to compare your career path with anyone else’s.

Also, today I'm focusing specifically on careers in bench research. Past industry career columns have described the many other roles scientists can have in industry — tech transfer , regulatory affairs , product sales and client support , medical affairs and so on.

Entry-level positions

Interns are the most temporary and entry-level positions in industry. As in other sectors, interns in industry (who are typically paid) work in a particular department or research division over a set course of time, typically three to six months. Internship opportunities may be more plentiful at the larger biotech and pharmaceutical companies, but it's always a good idea to reach out to a company you're interested in to ask if they have an internship program. Internships can be a great way for scientists in training — from undergraduate to Ph.D. level — to get experience in industry. Keep in mind that many internships do not lead to guaranteed jobs!

Laboratory technicians are largely support team members. They often play a role in making sure all the components are in place for researchers to conduct their experiments. This might involve making buffers, reagents or other similar tasks. Some lab tech jobs offer move involvement in experiments and research.

Research assistants or research associates perform the day-to-day research and experiments that keep projects moving forward. A master’s degree, or an equivalent amount of research experience, is often required. Of course, what that "equivalent" level of experience is will vary, but one to three years is typical. You might also see the job title “scientific researcher,” and that position has similar duties. With more experience, you can advance to senior research assistant (or, depending on the company, to research associate I/II/III ), which will involve more responsibility. This could include some managerial work or experimental design and analysis.

Mid-level positions

Some companies offer postdoctoral fellowships for those who have recently completed their Ph.D.s. Depending on the company, these might be temporary positions (for a span of months to years but typically no more than two to three years) or promise a job at the end. Make sure to do your research on postdoctoral fellowships, as many don’t have any guarantee of jobs at the end (and some companies actually won’t, as a policy, hire postdoctoral fellows from their own programs). This is a great way to get industry experience if you’re just starting out and want to get a feel for it. Most fellowships provide more opportunities to publish and present your research than in a typical scientist position, although this will, again, vary by the specific program and company.

Research scientists also have hands-on roles in day-to-day research but have additional leadership responsibilities. They might be leading a group of research assistants or other scientists, planning experiments, analyzing data and/or deciding the direction of research needed to fulfill project goals. These roles typically require Ph.D.s, although a master's degree plus experience is sometimes sufficient. It’s always a good idea to check the job description to see if your experience matches the requirements. Sometimes referred to as just “scientist.” this position also has various levels. Scientist I, II, and senior scientist have differing levels of responsibility and leadership, but all focus on completing and directing research experiments and projects.

Some companies have principal scientist positions that fall between scientist and director jobs. These have a mix of both job responsibilities — a lot of managing and big idea work, but still tight connections to the ongoing research projects.

Upper-level positions

Next in the hierarchy is the director . Director roles typically proceed through associate director, director, and then senior or executive director. Directors are less involved in the hands-on conducting of experiments and research (although their involvement may vary based on the size of the company). Instead, they focus more on the bigger picture: How do the current experimental data support the project? Is the current research in line with the company’s goals? These roles typically involve managing a group or team of other scientists as well (remember, industry loves teamwork!). Directors plan, oversee and direct the R&D operations within their divisions or departments. They also often are involved in developing strategy and operation plans for the company. As leaders, they are responsible for ensuring the R&D staff below them have the appropriate training and guidance to effectively do their jobs and move research forward.

The hierarchy after director positions gets less clear and depends on the individual company. Sometimes the next step is to become the head of a department, division or all R&D activities. Or a vice president title is next in line. In both cases, responsibilities shift further away from the bench and increasingly toward business management, development and companywide initiatives. A strong understanding of the research process and procedures is still required for these positions, so experience is a key factor when filling one of these positions.

As always, keep in mind that this is just an overview of what exists — not every company has every type of position, and a position might be listed under a slightly different name. Read the job description and qualifications to see if it matches with your degree and experience level. If you’re unsure if you’re under- or overqualified, you can reach out to someone at the company or apply anyways and get a better gauge during the interview process.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Courtney Chandler is a biochemist and microbiologist in Baltimore, Md., and a careers columnist for ASBMB Today.

Related articles

Featured jobs.

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles.

Upcoming opportunities

Friendly reminder: Book a recruiter table at ASBMB's career and education fair by Nov. 30 to secure early-bird pricing! Just added: Applications are being accepted for a post-bac at Dartmouth Cancer Center.

Just added: Register for ASBMB's virtual session on thriving in challenging academic or work environments.

Who decides when a grad student graduates?

Ph.D. programs often don’t have a set timeline. Students continue with their research until their thesis is done, which is where variability comes into play.

Submit an abstract for ASBMB's meeting on ferroptosis!

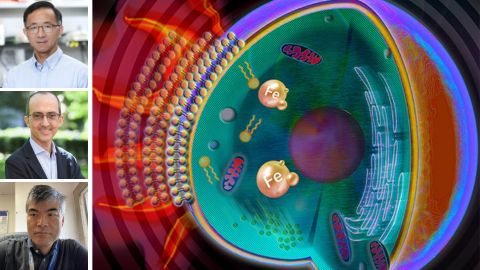

Join the pioneers of ferroptosis at cell death conference

Meet Brent Stockwell, Xuejun Jiang and Jin Ye — the co-chairs of the ASBMB’s 2025 meeting on metabolic cross talk and biochemical homeostasis research.

A brief history of the performance review

Performance reviews are a widely accepted practice across all industries — including pharma and biotech. Where did the practice come from, and why do companies continue to require them?

Home » Blog » CRA Career Progression & Levels

CRA Career Progression & Levels

One’s CRA career progression may be different depending on the company and business environment. However, with motivation and previous experience showing success in clinical research, one should be able to progress in their CRA career either within the same company or at another company. Below are different CRA job title levels that we can use as a rough guide in gauging CRA career progression:

CRA Levels, Job Titles & Descriptions

Cra i (clinical research associate i).

Typical Salary Range: $50,000 to $70,000/yr

This is commonly considered the first level in the CRA career progression. It’s an entry-level CRA role with 1-2 years of experience. CRA I may be working on different parts of a clinical trial, such as setting up trial master files, document preparation, and site correspondence. Some supervision from a more senior CRA may be needed to help guide a CRA I on different clinical trial related functions.

A CRA I is typically an entry-level position in the field of clinical research, aimed at those with some background in life sciences or a related field and perhaps some prior experience in clinical research settings. This role requires strong attention to detail, excellent organizational skills, and the ability to communicate effectively across various levels of the organization. Other duties and functions for a CRA I may be as follows:

- Conduct site visits to monitor compliance with the study protocol, Good Clinical Practice (GCP) , and applicable regulatory requirements.

- Evaluate the performance of the trial at the site, ensuring timely submission of proper data.

- Oversee the consent process to ensure that it meets ethical and regulatory standards.

- Monitor and verify the accuracy of clinical data collected during the study.

- Review and resolve discrepancies in clinical data with site personnel.

- Ensure the storage of study documents is secure and in compliance with data protection laws.

- Ensure all necessary site and investigator documents are up to date and compliant with local laws and regulations.

- Assist in preparing and reviewing submissions to regulatory bodies.

- Train site staff on regulatory compliance, protocol requirements, and other necessary aspects of the study.

- Serve as the primary communication link between the site and the sponsor.

- Prepare visit reports and other documentation in a timely and accurate manner.

- Attend project team meetings and provide updates on site status.

- Identify potential study issues and participate in the problem-solving process.

- Collaborate with other team members to ensure the smooth running of trials.

- Provide support to sites as needed to handle issues such as patient recruitment or retention.

- Participate in ongoing training in clinical trial management and regulations.

- Assist in the training of new site staff on protocols and compliance issues.

- Be willing to travel to conduct site visits and audits.

CRA II (Clinical Research Associate II)

Typical Salary Range: $65,000 to $90,000/yr

This is commonly a second level in the CRA career progression. It’s a mid-level position with 3-5 years of experience. A CRA II should be working on all stages of a clinical trial. Job functions can range from clinical trial design and planning, protocol and form generation, site selection, and monitoring, to clinical report generation. A CRA II should be working independently with little or some supervision from more senior CRA. Other duties and functions for a CRA II may be as follows:

- Independently conduct site visits, including initiation, monitoring, and close-out visits.

- Ensure comprehensive oversight of site performance and adherence to trial timelines and protocols.

- Manage multiple clinical trial sites with minimal supervision, ensuring high-quality data collection and protocol compliance.

- Take the lead on resolving complex data discrepancies and ensuring the integrity of clinical data through rigorous monitoring.

- Utilize advanced data management tools to track and report on trial progress.

- Ensure all clinical data are recorded, processed, and reported according to regulatory standards.

- Provide expert guidance on regulatory standards and changes to ensure all trial activities comply.

- Assist in the development and review of study protocols, informed consent forms, and other documents.

- Lead interactions with regulatory authorities during audits and inspections.

- Develop and maintain effective relationships with trial site staff, sponsors, and other stakeholders.

- Prepare and deliver detailed reports and presentations on trial status to senior management and sponsors.

- Lead team meetings, providing critical updates and strategic guidance.

- Identify, analyze, and lead the resolution of complex trial issues, ensuring minimal disruption to study timelines.

- Provide strategic solutions to enhance trial efficiency and outcomes.

- Act as a point of contact for crisis management at clinical sites.

- Mentor and support CRA I and other junior staff in clinical trial management practices.

- Lead training sessions on GCP, regulatory compliance, and specific study protocols.

- Share best practices and continual learning insights with the team.

- Travel extensively to manage and monitor trial sites, often handling more complex or problematic sites.

CRA (Clinical Research Associate III) / Senior CRA / Lead CRA

Typical Salary Range: $85,000 to $120,000/yr

This is usually considered the final level in the CRA career progression. It’s a senior-level role with 5 or more years of experience. A CRA III, Sr. CRA, or Lead CRA should be able to perform any of the clinical trial tasks proficiently. They are also expected to supervise, train, and mentor junior CRAs.

A CRA III / Senior CRA / Lead CRA is expected to deliver years of industry experience and deep knowledge of clinical research in their role. This position is important for meeting clinical trial objectives and requires strong leadership skills, an expert understanding of regulations, and the ability to drive improvements in the clinical research process. Other duties and functions for a CRA III may be as follows:

- Lead and manage the clinical monitoring aspects of projects, ensuring compliance with the clinical trial protocol, checking clinical site activities, making on-site visits, and reviewing Case Report Forms (CRFs).

- Provide authoritative oversight of trial conduct, handling the most complex or high-profile studies.

- Design strategies for site management to ensure optimal performance and results.

- Lead role in ensuring data integrity through meticulous monitoring and auditing of trial data.

- Develop and implement quality control processes to ensure adherence to all study, regulatory, and ethical standards.

- Oversee the creation and maintenance of trial documentation, ensuring comprehensive audit trails.

- Act as a senior expert on regulatory requirements and ensure all aspects of the trial are compliant with SOPs, FDA, and ICH guidelines.

- Lead submission of protocol, amendments, and other regulatory documents to relevant authorities.

- Direct interactions with regulatory agencies and respond to their queries.

- Facilitate effective communication channels between site staff, trial sponsors, and internal teams.

- Serve as the main point of contact for major operational aspects of the trial, providing reports and updates to stakeholders.

- Conduct critical meetings and contribute to strategic planning sessions.

- Identify systemic issues in clinical trials and develop innovative solutions to address them.

- Lead crisis management efforts during clinical trials, ensuring swift resolution of issues with minimal impact on outcomes.

- Implement new technologies and processes for more efficient trial management.

- Mentor and guide junior CRAs, CRA Is, and CRA IIs, providing training and development support.

- Develop training materials and standard operating procedures for clinical trial management.

- Lead by example in fostering a culture of continuous improvement and high ethical standards.

- Extensive travel to oversee trial sites, particularly those that are high-stakes or facing challenges.

- Manage relationships with trial site personnel to ensure the highest levels of cooperation and performance.

Career Progression Beyond a CRA Role

Many CRAs may choose to remain in CRA role as a career. Some CRAs may become consultants after gaining years of experience. Beyond a CRA role, CRA career progression may include management role such as:

- Clinical Trial or Clinical Affairs Manager

- Senior Clinical Trial or Clinical Affairs Manager

- Associate Director of Clinical Research

- Director / Vice President of Clinical research

The sky is the limit for opportunities and CRA career progression beyond just a CRA role. One note is that advanced degrees (M.D., Ph.D., MBA, etc.) may be an advantage as one progress higher in clinical research career. Another option is to get a certification through one of the certifying authorities in the clinical research field.

Ernie Sakchalathorn

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

ACRP Learning Update

ACRP is happy to announce forthcoming updates to several courses in the ACRP catalog.

Clinical Researcher

Navigating a Career as a Clinical Research Professional: Where to Begin?

Clinical Researcher June 9, 2020

Clinical Researcher—June 2020 (Volume 34, Issue 6)

PEER REVIEWED

Bridget Kesling, MACPR; Carolynn Jones, DNP, MSPH, RN, FAAN; Jessica Fritter, MACPR; Marjorie V. Neidecker, PhD, MEng, RN, CCRP

Those seeking an initial career in clinical research often ask how they can “get a start” in the field. Some clinical research professionals may not have heard about clinical research careers until they landed that first job. Individuals sometimes report that they have entered the field “accidentally” and were not previously prepared. Those trying to enter the clinical research field lament that it is hard to “get your foot in the door,” even for entry-level jobs and even if you have clinical research education. An understanding of how individuals enter the field can be beneficial to newcomers who are targeting clinical research as a future career path, including those novices who are in an academic program for clinical research professionals.

We designed a survey to solicit information from students and alumni of an online academic clinical research graduate program offered by a large public university. The purpose of the survey was to gain information about how individuals have entered the field of clinical research; to identify facilitators and barriers of entering the field, including advice from seasoned practitioners; and to share the collected data with individuals who wanted to better understand employment prospects in clinical research.

Core competencies established and adopted for clinical research professionals in recent years have informed their training and education curricula and serve as a basis for evaluating and progressing in the major roles associated with the clinical research enterprise.{1,2} Further, entire academic programs have emerged to provide degree options for clinical research,{3,4} and academic research sites are focusing on standardized job descriptions.

For instance, Duke University re-structured its multiple clinical research job descriptions to streamline job titles and progression pathways using a competency-based, tiered approach. This led to advancement pathways and impacted institutional turnover rates in relevant research-related positions.{5,6} Other large clinical research sites or contract research organizations (CROs) have structured their onboarding and training according to clinical research core competencies. Indeed, major professional organizations and U.S. National Institutes of Health initiatives have adopted the Joint Task Force for Clinical Trial Competency as the gold standard approach to organizing training and certification.{7,8}

Recent research has revealed that academic medical centers, which employ a large number of clinical research professionals, are suffering from high staff turnover rates in this arena, with issues such as uncertainty of the job, dissatisfaction with training, and unclear professional development and role progression pathways being reported as culprits in this turnover.{9} Further, CROs report a significant shortage of clinical research associate (CRA) personnel.{10} Therefore, addressing factors that would help novices gain initial jobs would address an important workforce gap.

This mixed-methods survey study was initiated by a student of a clinical research graduate program at a large Midwest university who wanted to know how to find her first job in clinical research. Current students and alumni of the graduate program were invited to participate in an internet-based survey in the fall semester of 2018 via e-mails sent through the program listservs of current and graduated students from the program’s lead faculty. After the initial e-mail, two reminders were sent to prospective participants.

The survey specifically targeted students or alumni who had worked in clinical research. We purposefully avoided those students with no previous clinical research work experience, since they would not be able to discuss their pathway into the field. We collected basic demographic information, student’s enrollment status, information about their first clinical research position (including how it was attained), and narrative information to describe their professional progression in clinical research. Additional information was solicited about professional organization membership and certification, and about the impact of graduate education on the acquisition of clinical research jobs and/or role progression.

The survey was designed so that all data gathered (from both objective responses and open-ended responses) were anonymous. The survey was designed using the internet survey instrument Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), which is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. REDCap provides an intuitive interface for validated data entry; audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and procedures for importing data from external sources.{11}

Data were exported to Excel files and summary data were used to describe results. Three questions solicited open-ended responses about how individuals learned about clinical research career options, how they obtained their first job, and their advice to novices seeking their first job in clinical research. Qualitative methods were used to identify themes from text responses. The project was submitted to the university’s institutional review board and was classified as exempt from requiring board oversight.

A total of 215 survey invitations were sent out to 90 current students and 125 graduates. Five surveys were returned as undeliverable. A total of 48 surveys (22.9%) were completed. Because the survey was designed to collect information from those who were working or have worked in clinical research, those individuals (n=5) who reported (in the first question) that they had never worked in clinical research were eliminated. After those adjustments, the total number completed surveys was 43 (a 20.5% completion rate).

The median age of the participants was 27 (range 22 to 59). The majority of respondents (89%) reported being currently employed as clinical research professionals and 80% were working in clinical research at the time of graduate program entry. The remaining respondents had worked in clinical research in the past. Collectively, participants’ clinical research experience ranged from less than one to 27 years.

Research assistant (20.9%) and clinical research coordinator (16.3%) were the most common first clinical research roles reported. However, a wide range of job titles were also reported. When comparing entry-level job titles of participants to their current job title, 28 (74%) respondents reported a higher level job title currently, compared to 10 (26%) who still had the same job title.

Twenty-four (65%) respondents were currently working at an academic medical center, with the remaining working with community medical centers or private practices (n=3); site management organizations or CROs (n=2); pharmaceutical or device companies (n=4); or the federal government (n=1).

Three respondents (8%) indicated that their employer used individualized development plans to aid in planning for professional advancement. We also asked if their current employer provided opportunities for professional growth and advancement. Among academic medical center respondents, 16 (67%) indicated in the affirmative. Respondents also affirmed growth opportunities in other employment settings, with the exception of one respondent working in government and one respondent working in a community medical center.

Twenty-five respondents indicated membership to a professional association, and of those, 60% reported being certified by either the Association of Clinical Research Professionals (ACRP) or the Society of Clinical Research Associates (SoCRA).

Open-Ended Responses

We asked three open-ended questions to gain personal perspectives of respondents about how they chose clinical research as a career, how they entered the field, and their advice for novices entering the profession. Participants typed narrative responses.

“Why did you decide to pursue a career in clinical research?”

This question was asked to find out how individuals made the decision to initially consider clinical research as a career. Only one person in the survey had exposure to clinical research as a career option in high school, and three learned about such career options as college undergraduates. One participant worked in clinical research as a transition to medical school, two as a transition to a doctoral degree program, and two with the desire to move from a bench (basic science) career to a clinical research career.

After college, individuals either happened across clinical research as a career “by accident” or through people they met. Some participants expressed that they found clinical research careers interesting (n=6) and provided an opportunity to contribute to patients or improvements in healthcare (n=7).

“How did you find out about your first job in clinical research?”

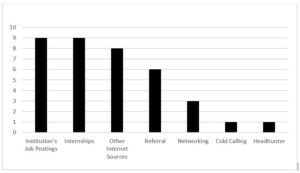

Qualitative responses were solicited to obtain information on how participants found their first jobs in clinical research. The major themes that were revealed are sorted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: How First Jobs in Clinical Research Were Found

Some reported finding their initial job through an institution’s job posting.

“I worked in the hospital in the clinical lab. I heard of the opening after I earned my bachelor’s and applied.”

Others reported finding about their clinical research position through the internet. Several did not know about clinical research roles before exploring a job posting.

“In reviewing jobs online, I noticed my BS degree fit the criteria to apply for a job in clinical research. I knew nothing about the field.”

“My friend recommended I look into jobs with a CRO because I wanted to transition out of a production laboratory.”

“I responded to an ad. I didn’t really know that research could be a profession though. I didn’t know anything about the field, principles, or daily activities.”

Some of the respondents reported moving into a permanent position after a role as an intern.

“My first clinical job came from an internship I did in my undergrad in basic sleep research. I thought I wanted to get into patient therapies, so I was able to transfer to addiction clinical trials from a basic science lab. And the clinical data management I did as an undergrad turned into a job after a few months.”

“I obtained a job directly from my graduate school practicum.”

“My research assistant internship [as an] undergrad provided some patient enrollment and consenting experience and led to a CRO position.”

Networking and referrals were other themes that respondents indicated had a direct impact on them finding initial employment in clinical research.

“I received a job opportunity (notice of an opening) through my e-mail from the graduate program.”

“I was a medical secretary for a physician who did research and he needed a full-time coordinator for a new study.”

“I was recommended by my manager at the time.”

“A friend had a similar position at the time. I was interested in learning more about the clinical research coordinator position.”

“What advice do you have for students and new graduates trying to enter their first role in clinical research?”

We found respondents (n=30) sorted into four distinct categories: 1) a general attitude/approach to job searching, 2) acquisition of knowledge/experience, 3) actions taken to get a position, and 4) personal attributes as a clinical research professional in their first job.

Respondents stressed the importance of flexibility and persistence (general attitude/approach) when seeking jobs. Moreover, 16 respondents stressed the importance of learning as much as they could about clinical research and gaining as much experience as they could in their jobs, encouraging them to ask a lot of questions. They also stressed a broader understanding of the clinical research enterprise, the impact that clinical research professional roles have on study participants and future patients, and the global nature of the enterprise.

“Apply for all research positions that sound interesting to you. Even if you don’t meet all the requirements, still apply.”

“Be persistent and flexible. Be willing to learn new skills and take on new responsibilities. This will help develop your own niche within a group/organization while creating opportunities for advancement.”

“Be flexible with salary requirements earlier in your career and push yourself to learn more [about the industry’s] standards [on] a global scale.”

“Be ever ready to adapt and change along with your projects, science, and policy. Never forget the journey the patients are on and that we are here to advance and support it.”

“Learning the big picture, how everything intertwines and works together, will really help you progress in the field.”

In addition to learning as much as one can about roles, skills, and the enterprise as a whole, advice was given to shadow or intern whenever possible—formally or through networking—and to be willing to start with a smaller company or with a lower position. The respondents stressed that novices entering the field will advance in their careers as they continue to gain knowledge and experience, and as they broaden their network of colleagues.

“Take the best opportunity available to you and work your way up, regardless [if it is] at clinical trial site or in industry.”

“Getting as much experience as possible is important; and learning about different career paths is important (i.e., not everyone wants or needs to be a coordinator, not everyone goes to graduate school to get a PhD, etc.).”

“(A graduate) program is beneficial as it provides an opportunity to learn the basics that would otherwise accompany a few years of entry-level work experience.”

“Never let an opportunity pass you up. Reach out directly to decision-makers via e-mail or telephone—don’t just rely on a job application website. Be willing to start at the bottom. Absolutely, and I cannot stress this enough, [you should] get experience at the site level, even if it’s just an internship or [as a] volunteer. I honestly feel that you need the site perspective to have success at the CRO or pharma level.”

Several personal behaviors were also stressed by respondents, such as knowing how to set boundaries, understanding how to demonstrate what they know, and ability to advocate for their progression. Themes such as doing a good job, communicating well, being a good team player, and sharing your passion also emerged.

“Be a team player, ask questions, and have a good attitude.”

“Be eager to share your passion and drive. Although you may lack clinical research experience, your knowledge and ambition can impress potential employers.”

“[A] HUGE thing is learning to sell yourself. Many people I work with at my current CRO have such excellent experience, and they are in low-level positions because they didn’t know how to negotiate/advocate for themselves as an employee.”

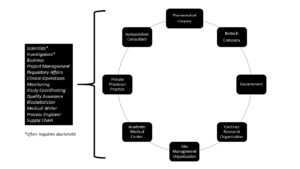

This mixed-methods study used purposeful sampling of students in an academic clinical research program to gain an understanding of how novices to the field find their initial jobs in the clinical research enterprise; how to transition to a clinical research career; and how to find opportunities for career advancement. There are multiple clinical research careers and employers (see Figure 2) available to individuals working in the clinical research enterprise.

Figure 2: Employers and Sample Careers

Despite the need for employees in the broad field of clinical research, finding a pathway to enter the field can be difficult for novices. The lack of knowledge about clinical research as a career option at the high school and college level points to an opportunity for broader inclusion of these careers in high school and undergraduate curricula, or as an option for guidance counselors to be aware of and share with students.

Because most clinical research jobs appear to require previous experience in order to gain entry, novices are often put into a “Catch-22” situation. However, once hired, upward mobility does exist, and was demonstrated in this survey. Mobility in clinical research careers (moving up and general turnover) may occur for a variety of reasons—usually to achieve a higher salary, to benefit from an improved work environment, or to thwart a perceived lack of progression opportunity.{9}

During COVID-19, there may be hiring freezes or furloughs of clinical research staff, but those personnel issues are predicted to be temporary. Burnout has also been reported as an issue among study coordinators, due to research study complexity and workload issues.{12} Moreover, the lack of individualized development planning revealed by our sample may indicate a unique workforce development need across roles of clinical research professionals.

This survey study is limited in that it is a small sample taken specifically from a narrow cohort of individuals who had obtained or were seeking a graduate degree in clinical research at a single institution. The study only surveyed those currently working in or who have a work history in clinical research. Moreover, the majority of respondents were employed at an academic medical center, which may not fully reflect the general population of clinical research professionals.

It was heartening to see the positive advancement in job titles for those individuals who had been employed in clinical research at program entry, compared to when they responded to the survey. However, the sample was too small to draw reliable correlations about job seeking or progression.

Although finding one’s first job in clinical research can be a lengthy and discouraging process, it is important to know that the opportunities are endless. Search in employment sites such as Indeed.com, but also search within job postings for targeted companies or research sites such as biopharmguy.com (see Table 1). Created a LinkedIn account and join groups and make connections. Participants in this study offered sound advice and tips for success in landing a job (see Figure 3).

Table 1: Sample Details from an Indeed.Com Job Search

Note: WCG = WIRB Copernicus Group

Figure 3: Twelve Tips for Finding Your First Job

- Seek out internships and volunteer opportunities

- Network, network, network

- Be flexible and persistent

- Learn as much as possible about clinical research

- Consider a degree in clinical research

- Ask a lot of questions of professionals working in the field

- Apply for all research positions that interest you, even if you think you are not qualified

- Be willing to learn new skills and take on new responsibilities

- Take the best opportunity available to you and work your way up

- Learn to sell yourself

- Sharpen communication (written and oral) and other soft skills

- Create an ePortfolio or LinkedIn account

Being willing to start at the ground level and working upwards was described as a positive approach because moving up does happen, and sometimes quickly. Also, learning soft skills in communication and networking were other suggested strategies. Gaining education in clinical research is one way to begin to acquire knowledge and applied skills and opportunities to network with experienced classmates who are currently working in the field.

Most individuals entering an academic program have found success in obtaining an initial job in clinical research, often before graduation. In fact, the student initiating the survey found a position in a CRO before graduation.

- Sonstein S, Seltzer J, Li R, Jones C, Silva H, Daemen E. 2014. Moving from compliance to competency: a harmonized core competency framework for the clinical research professional. Clinical Researcher 28(3):17–23. doi:10.14524/CR-14-00002R1.1. https://acrpnet.org/crjune2014/

- Sonstein S, Brouwer RN, Gluck W, et al. 2018. Leveling the joint task force core competencies for clinical research professionals. Therap Innov Reg Sci .

- Jones CT, Benner J, Jelinek K, et al. 2016. Academic preparation in clinical research: experience from the field. Clinical Researcher 30(6):32–7. doi:10.14524/CR-16-0020. https://acrpnet.org/2016/12/01/academic-preparation-in-clinical-research-experience-from-the-field/

- Jones CT, Gladson B, Butler J. 2015. Academic programs that produce clinical research professionals. DIA Global Forum 7:16–9.

- Brouwer RN, Deeter C, Hannah D, et al. 2017. Using competencies to transform clinical research job classifications. J Res Admin 48:11–25.

- Stroo M, Ashfaw K, Deeter C, et al. 2020. Impact of implementing a competency-based job framework for clinical research professionals on employee turnover. J Clin Transl Sci.

- Calvin-Naylor N, Jones C, Wartak M, et al. 2017. Education and training of clinical and translational study investigators and research coordinators: a competency-based approach. J Clin Transl Sci 1:16–25. doi:10.1017/cts.2016.2

- Development, Implementation and Assessment of Novel Training in Domain-based Competencies (DIAMOND). Center for Leading Innovation and Collaboration (CLIC). 2019. https://clic-ctsa.org/diamond

- Clinical Trials Talent Survey Report. 2018. http://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/node/351341/done?sid=15167

- Causey M. 2020. CRO workforce turnover hits new high. ACRP Blog . https://acrpnet.org/2020/01/08/cro-workforce-turnover-hits-new-high/

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42:377–81.

- Gwede CK, Johnson DJ, Roberts C, Cantor AB. 2005. Burnout in clinical research coordinators in the United States. Oncol Nursing Forum 32:1123–30.

A portion of this work was supported by the OSU CCTS, CTSA Grant #UL01TT002733.

Bridget Kesling, MACPR, ( [email protected] ) is a Project Management Analyst with IQVIA in Durham, N.C.

Carolynn Jones, DNP, MSPH, RN, FAAN, ( [email protected] ) is an Associate Professor of Clinical Nursing at The Ohio State University College of Nursing, Co-Director of Workforce Development for the university’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science, and Director of the university’s Master of Clinical Research program.

Jessica Fritter, MACPR, ( [email protected] ) is a Clinical Research Administration Manager at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an Instructor for the Master of Clinical Research program at The Ohio State University.

Marjorie V. Neidecker, PhD, MEng, RN, CCRP, ( [email protected] ) is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Nursing at The Ohio State University Colleges of Nursing and Pharmacy.

Optimizing Clinical Trial Education in Academia

A Case Study on Training Initiatives to Support Clinical Researchers with Electronic Medical Records

Back to Basics with Research Education

Research Assistant job profile

What is a Research Assistant?

Research assistants are involved in providing support to scientists or other types of researchers who are conducting experiments or gathering information in order to make new discoveries.

Job description

Specific duties can vary greatly depending on the industry in which they work and the type of research that is being carried out, however they will typically be required to:

- Plan research projects and coordinate roles within the projects

- Help conduct experiments and research alongside scientists

- Collect and log data collected

- Conduct data analysis and produce findings reports

- Present findings or produce presentations for researchers to present findings

- Maintain laboratory equipment

Why become a Research Assistant?

There are a number of reasons why one might want to consider getting this job, the main one being that it gives the opportunity to play a part in making pioneering, innovative discoveries that have the potential to change lives. Becoming a research assistant is also a great way to build on experience and skills learnt within university, which then enables you to progress onto more senior roles or roles within other parts of a business.

Types of employers

At present, most research assistants are working within the biotechnology sector as the sector continues to grow at a rapid rate. This is because biotechnology involves utilising living organisms in order to produce new products and processes, which is used heavily within healthcare and medicine. However, research assistants can also work for companies within industries including chemicals, biochemistry, pharmaceuticals, and proteins.

Within these industries, and more specifically, the types of employers that tend to actively recruit for this type of job include:

- Universities

- Clinical research organisations

- Private hospitals and NHS trusts

- R&D organisations

- Health related charities

To find out who’s hiring right now, you can search our research assistant jobs here .

Qualifications and experience required

To become a Research Assistant, a bachelor’s degree is usually required within a subject that is relevant to the field of research that is going to be carried out within the role, or the industry within which you are going to be working. Employers often value coursework or dissertations that have been completed as part of the degree, as these can be a good representation of the in-depth knowledge that you hold about the field of research.

Whilst prior experience is not always required in order to become a Research Assistant, practical experience within a laboratory and with the range of techniques typically used will greatly improve your chances when applying for jobs. This can be gained through a placement year during your degree, or summer voluntary work programmes. It is important to try to gain experience in both academia and in industry to help illustrate your competency, as well as inform your future career choices.

Visit our Resources page to download CV and cover letter templates here .

Salary expectations

A research assistant’s salary can vary based on location as well as the type of industry and company that they are working for. It can also vary greatly based on the qualifications (for example, BSc versus masters) and the level of experience held before joining the team.

Within the waste industry, salaries are likely to be close to minimum wage, whereas research assistants in the chemical industry, for example, could be looking at around £26,000. As requirements are fairly low for these roles, salaries will usually be basic until you have progressed into a more senior role or gained some experience.

How to become a research assistant

In order to become a Research Assistant, there are a number of basic skills that you should be able to demonstrate to an employer, including:

- Technical skills, as the role requires the use of lab equipment and innovative technologies

- Observational and analytical skills, as well as patience

- Problem-solving skills

- Good time-management and organisational skills

- The ability to communicate and network effectively

- Good scientific knowledge

Depending on the industry and type of employer you are aiming to work for, there are a variety of ways to search for Research Assistant jobs. University and hospital websites are a great place to start, as well as professional networking sites such as LinkedIn. Specialist recruitment agencies, such as CK Science, are another effective way to search for and land jobs, as they are able to offer tailored support and advice.

Sign up to CK+ to apply for roles at the click of a button and receive job alerts straight to your inbox here .

Career progression

As a Research Assistant, career progression is fairly fruitful. Through experience, undertaking many research projects and publishing work, you can aim towards becoming a senior researcher or professor leading your own team of individuals. This offers significantly increased responsibility as well as resources.

You may also want to look at progressing into other areas of the company or organisation that you are working for, such as media, management or consultancy.

Related jobs

- Laboratory Technician – supports complex scientific investigations by carrying out routine laboratory-based technical tasks and experiments, such as sampling, testing and recording results.

- Pharmacologist – conducts in vitro or in vivo research predict what effects new medicines might have on humans or animals so that they can be used and administered safely.

- Microbiologist – studies the microorganisms that cause infections, to understand how they work and how they can be used to enhance the quality of human life.

Search research assistant jobs

Visit the Advice Centre for job hunting, interview, CV and workplace tips

Read our ‘day in the life’ interviews

Advice centre

Free resources

Job profiles

Research and knowledge

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Most CRAs are current or former nurses who have experience as a research coordinator or a research assistant. Many universities now offer bachelor's, master's, and certificate programs in clinical research as another form of training for these research related roles. ... 7 thoughts on "Career Progression in Clinical Research ...

The scope of responsibilities and daily activities of a Research Assistant can significantly vary based on their experience level. Entry-level Research Assistants are typically focused on learning research methodologies and supporting senior researchers, while mid-level Research Assistants take on more complex tasks and may begin to manage certain aspects of the research process.

This might involve making buffers, reagents or other similar tasks. Some lab tech jobs offer move involvement in experiments and research. Research assistants or research associates perform the day-to-day research and experiments that keep projects moving forward. A master's degree, or an equivalent amount of research experience, is often ...

Before beginning your education as part of a research assistant career path, you should take time to determine what field you want to work in. For example, the classes that a law research assistant needs to take differ from the educational needs of a medical lab research assistant. 2. Earn a bachelor's degree

Below are different CRA job title levels that we can use as a rough guide in gauging CRA career progression: CRA Levels, Job Titles & Descriptions CRA I (Clinical Research Associate I) Typical Salary Range: $50,000 to $70,000/yr. This is commonly considered the first level in the CRA career progression.

Research assistant (20.9%) and clinical research coordinator (16.3%) were the most common first clinical research roles reported. However, a wide range of job titles were also reported. When comparing entry-level job titles of participants to their current job title, 28 (74%) respondents reported a higher level job title currently, compared to ...

Explore new Research Assistant job openings and options for career transitions into related roles. Read More. Steps to Become a Research Assistant If you thrive in an environment where you can spend your days collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data, consider a career as a research assistant. Pursue this position by following these steps:

Research assistants often play a vital role in designing experiments and studies. Collaborating with senior researchers, you'll contribute to the development of research protocols, experimental designs, and data collection procedures. This requires a solid understanding of research methodologies and the ability to think critically and creatively.

Career progression. As a Research Assistant, career progression is fairly fruitful. Through experience, undertaking many research projects and publishing work, you can aim towards becoming a senior researcher or professor leading your own team of individuals. This offers significantly increased responsibility as well as resources.

A Clinical Research Assistant typically begins their career with a bachelor's degree in a related field such as biology, health sciences, or nursing. They often gain initial experience through internships or entry-level positions in healthcare or research settings. As they progress, they may pursue certifications like the Certified Clinical ...