- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- The PRISMA 2020...

The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews

PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews

- Related content

- Peer review

- Joanne E McKenzie , associate professor 1 ,

- Patrick M Bossuyt , professor 2 ,

- Isabelle Boutron , professor 3 ,

- Tammy C Hoffmann , professor 4 ,

- Cynthia D Mulrow , professor 5 ,

- Larissa Shamseer , doctoral student 6 ,

- Jennifer M Tetzlaff , research product specialist 7 ,

- Elie A Akl , professor 8 ,

- Sue E Brennan , senior research fellow 1 ,

- Roger Chou , professor 9 ,

- Julie Glanville , associate director 10 ,

- Jeremy M Grimshaw , professor 11 ,

- Asbjørn Hróbjartsson , professor 12 ,

- Manoj M Lalu , associate scientist and assistant professor 13 ,

- Tianjing Li , associate professor 14 ,

- Elizabeth W Loder , professor 15 ,

- Evan Mayo-Wilson , associate professor 16 ,

- Steve McDonald , senior research fellow 1 ,

- Luke A McGuinness , research associate 17 ,

- Lesley A Stewart , professor and director 18 ,

- James Thomas , professor 19 ,

- Andrea C Tricco , scientist and associate professor 20 ,

- Vivian A Welch , associate professor 21 ,

- Penny Whiting , associate professor 17 ,

- David Moher , director and professor 22

- 1 School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

- 2 Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Amsterdam University Medical Centres, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 3 Université de Paris, Centre of Epidemiology and Statistics (CRESS), Inserm, F 75004 Paris, France

- 4 Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare, Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia

- 5 University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, USA; Annals of Internal Medicine

- 6 Knowledge Translation Program, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, Toronto, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- 7 Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada

- 8 Clinical Research Institute, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon; Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

- 9 Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, USA

- 10 York Health Economics Consortium (YHEC Ltd), University of York, York, UK

- 11 Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada; Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- 12 Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Odense (CEBMO) and Cochrane Denmark, Department of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; Open Patient data Exploratory Network (OPEN), Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark

- 13 Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Canada; Clinical Epidemiology Program, Blueprint Translational Research Group, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; Regenerative Medicine Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada

- 14 Department of Ophthalmology, School of Medicine, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado, United States; Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

- 15 Division of Headache, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Head of Research, The BMJ , London, UK

- 16 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Indiana University School of Public Health-Bloomington, Bloomington, Indiana, USA

- 17 Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

- 18 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York, UK

- 19 EPPI-Centre, UCL Social Research Institute, University College London, London, UK

- 20 Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael's Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Epidemiology Division of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and the Institute of Health Management, Policy, and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Queen's Collaboration for Health Care Quality Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, Queen's University, Kingston, Canada

- 21 Methods Centre, Bruyère Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- 22 Centre for Journalology, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- Correspondence to: M J Page matthew.page{at}monash.edu

- Accepted 4 January 2021

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement, published in 2009, was designed to help systematic reviewers transparently report why the review was done, what the authors did, and what they found. Over the past decade, advances in systematic review methodology and terminology have necessitated an update to the guideline. The PRISMA 2020 statement replaces the 2009 statement and includes new reporting guidance that reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesise studies. The structure and presentation of the items have been modified to facilitate implementation. In this article, we present the PRISMA 2020 27-item checklist, an expanded checklist that details reporting recommendations for each item, the PRISMA 2020 abstract checklist, and the revised flow diagrams for original and updated reviews.

Systematic reviews serve many critical roles. They can provide syntheses of the state of knowledge in a field, from which future research priorities can be identified; they can address questions that otherwise could not be answered by individual studies; they can identify problems in primary research that should be rectified in future studies; and they can generate or evaluate theories about how or why phenomena occur. Systematic reviews therefore generate various types of knowledge for different users of reviews (such as patients, healthcare providers, researchers, and policy makers). 1 2 To ensure a systematic review is valuable to users, authors should prepare a transparent, complete, and accurate account of why the review was done, what they did (such as how studies were identified and selected) and what they found (such as characteristics of contributing studies and results of meta-analyses). Up-to-date reporting guidance facilitates authors achieving this. 3

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement published in 2009 (hereafter referred to as PRISMA 2009) 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 is a reporting guideline designed to address poor reporting of systematic reviews. 11 The PRISMA 2009 statement comprised a checklist of 27 items recommended for reporting in systematic reviews and an “explanation and elaboration” paper 12 13 14 15 16 providing additional reporting guidance for each item, along with exemplars of reporting. The recommendations have been widely endorsed and adopted, as evidenced by its co-publication in multiple journals, citation in over 60 000 reports (Scopus, August 2020), endorsement from almost 200 journals and systematic review organisations, and adoption in various disciplines. Evidence from observational studies suggests that use of the PRISMA 2009 statement is associated with more complete reporting of systematic reviews, 17 18 19 20 although more could be done to improve adherence to the guideline. 21

Many innovations in the conduct of systematic reviews have occurred since publication of the PRISMA 2009 statement. For example, technological advances have enabled the use of natural language processing and machine learning to identify relevant evidence, 22 23 24 methods have been proposed to synthesise and present findings when meta-analysis is not possible or appropriate, 25 26 27 and new methods have been developed to assess the risk of bias in results of included studies. 28 29 Evidence on sources of bias in systematic reviews has accrued, culminating in the development of new tools to appraise the conduct of systematic reviews. 30 31 Terminology used to describe particular review processes has also evolved, as in the shift from assessing “quality” to assessing “certainty” in the body of evidence. 32 In addition, the publishing landscape has transformed, with multiple avenues now available for registering and disseminating systematic review protocols, 33 34 disseminating reports of systematic reviews, and sharing data and materials, such as preprint servers and publicly accessible repositories. To capture these advances in the reporting of systematic reviews necessitated an update to the PRISMA 2009 statement.

Summary points

To ensure a systematic review is valuable to users, authors should prepare a transparent, complete, and accurate account of why the review was done, what they did, and what they found

The PRISMA 2020 statement provides updated reporting guidance for systematic reviews that reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesise studies

The PRISMA 2020 statement consists of a 27-item checklist, an expanded checklist that details reporting recommendations for each item, the PRISMA 2020 abstract checklist, and revised flow diagrams for original and updated reviews

We anticipate that the PRISMA 2020 statement will benefit authors, editors, and peer reviewers of systematic reviews, and different users of reviews, including guideline developers, policy makers, healthcare providers, patients, and other stakeholders

Development of PRISMA 2020

A complete description of the methods used to develop PRISMA 2020 is available elsewhere. 35 We identified PRISMA 2009 items that were often reported incompletely by examining the results of studies investigating the transparency of reporting of published reviews. 17 21 36 37 We identified possible modifications to the PRISMA 2009 statement by reviewing 60 documents providing reporting guidance for systematic reviews (including reporting guidelines, handbooks, tools, and meta-research studies). 38 These reviews of the literature were used to inform the content of a survey with suggested possible modifications to the 27 items in PRISMA 2009 and possible additional items. Respondents were asked whether they believed we should keep each PRISMA 2009 item as is, modify it, or remove it, and whether we should add each additional item. Systematic review methodologists and journal editors were invited to complete the online survey (110 of 220 invited responded). We discussed proposed content and wording of the PRISMA 2020 statement, as informed by the review and survey results, at a 21-member, two-day, in-person meeting in September 2018 in Edinburgh, Scotland. Throughout 2019 and 2020, we circulated an initial draft and five revisions of the checklist and explanation and elaboration paper to co-authors for feedback. In April 2020, we invited 22 systematic reviewers who had expressed interest in providing feedback on the PRISMA 2020 checklist to share their views (via an online survey) on the layout and terminology used in a preliminary version of the checklist. Feedback was received from 15 individuals and considered by the first author, and any revisions deemed necessary were incorporated before the final version was approved and endorsed by all co-authors.

The PRISMA 2020 statement

Scope of the guideline.

The PRISMA 2020 statement has been designed primarily for systematic reviews of studies that evaluate the effects of health interventions, irrespective of the design of the included studies. However, the checklist items are applicable to reports of systematic reviews evaluating other interventions (such as social or educational interventions), and many items are applicable to systematic reviews with objectives other than evaluating interventions (such as evaluating aetiology, prevalence, or prognosis). PRISMA 2020 is intended for use in systematic reviews that include synthesis (such as pairwise meta-analysis or other statistical synthesis methods) or do not include synthesis (for example, because only one eligible study is identified). The PRISMA 2020 items are relevant for mixed-methods systematic reviews (which include quantitative and qualitative studies), but reporting guidelines addressing the presentation and synthesis of qualitative data should also be consulted. 39 40 PRISMA 2020 can be used for original systematic reviews, updated systematic reviews, or continually updated (“living”) systematic reviews. However, for updated and living systematic reviews, there may be some additional considerations that need to be addressed. Where there is relevant content from other reporting guidelines, we reference these guidelines within the items in the explanation and elaboration paper 41 (such as PRISMA-Search 42 in items 6 and 7, Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) reporting guideline 27 in item 13d). Box 1 includes a glossary of terms used throughout the PRISMA 2020 statement.

Glossary of terms

Systematic review —A review that uses explicit, systematic methods to collate and synthesise findings of studies that address a clearly formulated question 43

Statistical synthesis —The combination of quantitative results of two or more studies. This encompasses meta-analysis of effect estimates (described below) and other methods, such as combining P values, calculating the range and distribution of observed effects, and vote counting based on the direction of effect (see McKenzie and Brennan 25 for a description of each method)

Meta-analysis of effect estimates —A statistical technique used to synthesise results when study effect estimates and their variances are available, yielding a quantitative summary of results 25

Outcome —An event or measurement collected for participants in a study (such as quality of life, mortality)

Result —The combination of a point estimate (such as a mean difference, risk ratio, or proportion) and a measure of its precision (such as a confidence/credible interval) for a particular outcome

Report —A document (paper or electronic) supplying information about a particular study. It could be a journal article, preprint, conference abstract, study register entry, clinical study report, dissertation, unpublished manuscript, government report, or any other document providing relevant information

Record —The title or abstract (or both) of a report indexed in a database or website (such as a title or abstract for an article indexed in Medline). Records that refer to the same report (such as the same journal article) are “duplicates”; however, records that refer to reports that are merely similar (such as a similar abstract submitted to two different conferences) should be considered unique.

Study —An investigation, such as a clinical trial, that includes a defined group of participants and one or more interventions and outcomes. A “study” might have multiple reports. For example, reports could include the protocol, statistical analysis plan, baseline characteristics, results for the primary outcome, results for harms, results for secondary outcomes, and results for additional mediator and moderator analyses

PRISMA 2020 is not intended to guide systematic review conduct, for which comprehensive resources are available. 43 44 45 46 However, familiarity with PRISMA 2020 is useful when planning and conducting systematic reviews to ensure that all recommended information is captured. PRISMA 2020 should not be used to assess the conduct or methodological quality of systematic reviews; other tools exist for this purpose. 30 31 Furthermore, PRISMA 2020 is not intended to inform the reporting of systematic review protocols, for which a separate statement is available (PRISMA for Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement 47 48 ). Finally, extensions to the PRISMA 2009 statement have been developed to guide reporting of network meta-analyses, 49 meta-analyses of individual participant data, 50 systematic reviews of harms, 51 systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy studies, 52 and scoping reviews 53 ; for these types of reviews we recommend authors report their review in accordance with the recommendations in PRISMA 2020 along with the guidance specific to the extension.

How to use PRISMA 2020

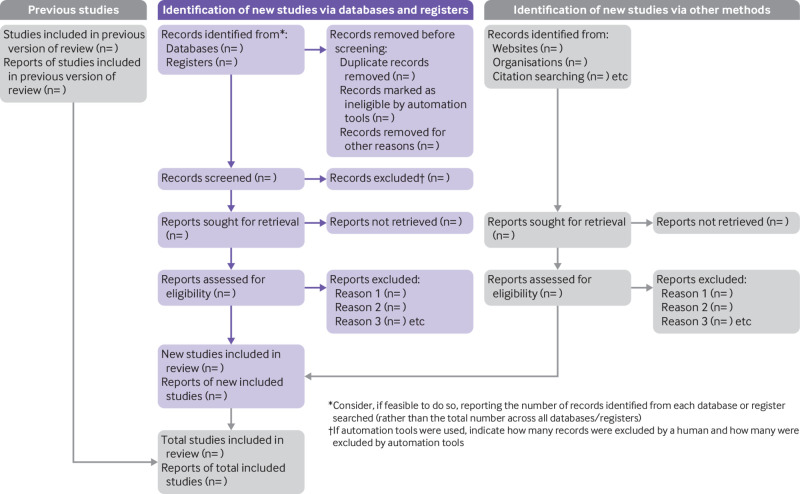

The PRISMA 2020 statement (including the checklists, explanation and elaboration, and flow diagram) replaces the PRISMA 2009 statement, which should no longer be used. Box 2 summarises noteworthy changes from the PRISMA 2009 statement. The PRISMA 2020 checklist includes seven sections with 27 items, some of which include sub-items ( table 1 ). A checklist for journal and conference abstracts for systematic reviews is included in PRISMA 2020. This abstract checklist is an update of the 2013 PRISMA for Abstracts statement, 54 reflecting new and modified content in PRISMA 2020 ( table 2 ). A template PRISMA flow diagram is provided, which can be modified depending on whether the systematic review is original or updated ( fig 1 ).

Noteworthy changes to the PRISMA 2009 statement

Inclusion of the abstract reporting checklist within PRISMA 2020 (see item #2 and table 2 ).

Movement of the ‘Protocol and registration’ item from the start of the Methods section of the checklist to a new Other section, with addition of a sub-item recommending authors describe amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol (see item #24a-24c).

Modification of the ‘Search’ item to recommend authors present full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites searched, not just at least one database (see item #7).

Modification of the ‘Study selection’ item in the Methods section to emphasise the reporting of how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process (see item #8).

Addition of a sub-item to the ‘Data items’ item recommending authors report how outcomes were defined, which results were sought, and methods for selecting a subset of results from included studies (see item #10a).

Splitting of the ‘Synthesis of results’ item in the Methods section into six sub-items recommending authors describe: the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis; any methods required to prepare the data for synthesis; any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses; any methods used to synthesise results; any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (such as subgroup analysis, meta-regression); and any sensitivity analyses used to assess robustness of the synthesised results (see item #13a-13f).

Addition of a sub-item to the ‘Study selection’ item in the Results section recommending authors cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded (see item #16b).

Splitting of the ‘Synthesis of results’ item in the Results section into four sub-items recommending authors: briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among studies contributing to the synthesis; present results of all statistical syntheses conducted; present results of any investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results; and present results of any sensitivity analyses (see item #20a-20d).

Addition of new items recommending authors report methods for and results of an assessment of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome (see items #15 and #22).

Addition of a new item recommending authors declare any competing interests (see item #26).

Addition of a new item recommending authors indicate whether data, analytic code and other materials used in the review are publicly available and if so, where they can be found (see item #27).

PRISMA 2020 item checklist

- View inline

PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist*

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram template for systematic reviews. The new design is adapted from flow diagrams proposed by Boers, 55 Mayo-Wilson et al. 56 and Stovold et al. 57 The boxes in grey should only be completed if applicable; otherwise they should be removed from the flow diagram. Note that a “report” could be a journal article, preprint, conference abstract, study register entry, clinical study report, dissertation, unpublished manuscript, government report or any other document providing relevant information.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

We recommend authors refer to PRISMA 2020 early in the writing process, because prospective consideration of the items may help to ensure that all the items are addressed. To help keep track of which items have been reported, the PRISMA statement website ( http://www.prisma-statement.org/ ) includes fillable templates of the checklists to download and complete (also available in the data supplement on bmj.com). We have also created a web application that allows users to complete the checklist via a user-friendly interface 58 (available at https://prisma.shinyapps.io/checklist/ and adapted from the Transparency Checklist app 59 ). The completed checklist can be exported to Word or PDF. Editable templates of the flow diagram can also be downloaded from the PRISMA statement website.

We have prepared an updated explanation and elaboration paper, in which we explain why reporting of each item is recommended and present bullet points that detail the reporting recommendations (which we refer to as elements). 41 The bullet-point structure is new to PRISMA 2020 and has been adopted to facilitate implementation of the guidance. 60 61 An expanded checklist, which comprises an abridged version of the elements presented in the explanation and elaboration paper, with references and some examples removed, is available in the data supplement on bmj.com. Consulting the explanation and elaboration paper is recommended if further clarity or information is required.

Journals and publishers might impose word and section limits, and limits on the number of tables and figures allowed in the main report. In such cases, if the relevant information for some items already appears in a publicly accessible review protocol, referring to the protocol may suffice. Alternatively, placing detailed descriptions of the methods used or additional results (such as for less critical outcomes) in supplementary files is recommended. Ideally, supplementary files should be deposited to a general-purpose or institutional open-access repository that provides free and permanent access to the material (such as Open Science Framework, Dryad, figshare). A reference or link to the additional information should be included in the main report. Finally, although PRISMA 2020 provides a template for where information might be located, the suggested location should not be seen as prescriptive; the guiding principle is to ensure the information is reported.

Use of PRISMA 2020 has the potential to benefit many stakeholders. Complete reporting allows readers to assess the appropriateness of the methods, and therefore the trustworthiness of the findings. Presenting and summarising characteristics of studies contributing to a synthesis allows healthcare providers and policy makers to evaluate the applicability of the findings to their setting. Describing the certainty in the body of evidence for an outcome and the implications of findings should help policy makers, managers, and other decision makers formulate appropriate recommendations for practice or policy. Complete reporting of all PRISMA 2020 items also facilitates replication and review updates, as well as inclusion of systematic reviews in overviews (of systematic reviews) and guidelines, so teams can leverage work that is already done and decrease research waste. 36 62 63

We updated the PRISMA 2009 statement by adapting the EQUATOR Network’s guidance for developing health research reporting guidelines. 64 We evaluated the reporting completeness of published systematic reviews, 17 21 36 37 reviewed the items included in other documents providing guidance for systematic reviews, 38 surveyed systematic review methodologists and journal editors for their views on how to revise the original PRISMA statement, 35 discussed the findings at an in-person meeting, and prepared this document through an iterative process. Our recommendations are informed by the reviews and survey conducted before the in-person meeting, theoretical considerations about which items facilitate replication and help users assess the risk of bias and applicability of systematic reviews, and co-authors’ experience with authoring and using systematic reviews.

Various strategies to increase the use of reporting guidelines and improve reporting have been proposed. They include educators introducing reporting guidelines into graduate curricula to promote good reporting habits of early career scientists 65 ; journal editors and regulators endorsing use of reporting guidelines 18 ; peer reviewers evaluating adherence to reporting guidelines 61 66 ; journals requiring authors to indicate where in their manuscript they have adhered to each reporting item 67 ; and authors using online writing tools that prompt complete reporting at the writing stage. 60 Multi-pronged interventions, where more than one of these strategies are combined, may be more effective (such as completion of checklists coupled with editorial checks). 68 However, of 31 interventions proposed to increase adherence to reporting guidelines, the effects of only 11 have been evaluated, mostly in observational studies at high risk of bias due to confounding. 69 It is therefore unclear which strategies should be used. Future research might explore barriers and facilitators to the use of PRISMA 2020 by authors, editors, and peer reviewers, designing interventions that address the identified barriers, and evaluating those interventions using randomised trials. To inform possible revisions to the guideline, it would also be valuable to conduct think-aloud studies 70 to understand how systematic reviewers interpret the items, and reliability studies to identify items where there is varied interpretation of the items.

We encourage readers to submit evidence that informs any of the recommendations in PRISMA 2020 (via the PRISMA statement website: http://www.prisma-statement.org/ ). To enhance accessibility of PRISMA 2020, several translations of the guideline are under way (see available translations at the PRISMA statement website). We encourage journal editors and publishers to raise awareness of PRISMA 2020 (for example, by referring to it in journal “Instructions to authors”), endorsing its use, advising editors and peer reviewers to evaluate submitted systematic reviews against the PRISMA 2020 checklists, and making changes to journal policies to accommodate the new reporting recommendations. We recommend existing PRISMA extensions 47 49 50 51 52 53 71 72 be updated to reflect PRISMA 2020 and advise developers of new PRISMA extensions to use PRISMA 2020 as the foundation document.

We anticipate that the PRISMA 2020 statement will benefit authors, editors, and peer reviewers of systematic reviews, and different users of reviews, including guideline developers, policy makers, healthcare providers, patients, and other stakeholders. Ultimately, we hope that uptake of the guideline will lead to more transparent, complete, and accurate reporting of systematic reviews, thus facilitating evidence based decision making.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this paper to the late Douglas G Altman and Alessandro Liberati, whose contributions were fundamental to the development and implementation of the original PRISMA statement.

We thank the following contributors who completed the survey to inform discussions at the development meeting: Xavier Armoiry, Edoardo Aromataris, Ana Patricia Ayala, Ethan M Balk, Virginia Barbour, Elaine Beller, Jesse A Berlin, Lisa Bero, Zhao-Xiang Bian, Jean Joel Bigna, Ferrán Catalá-López, Anna Chaimani, Mike Clarke, Tammy Clifford, Ioana A Cristea, Miranda Cumpston, Sofia Dias, Corinna Dressler, Ivan D Florez, Joel J Gagnier, Chantelle Garritty, Long Ge, Davina Ghersi, Sean Grant, Gordon Guyatt, Neal R Haddaway, Julian PT Higgins, Sally Hopewell, Brian Hutton, Jamie J Kirkham, Jos Kleijnen, Julia Koricheva, Joey SW Kwong, Toby J Lasserson, Julia H Littell, Yoon K Loke, Malcolm R Macleod, Chris G Maher, Ana Marušic, Dimitris Mavridis, Jessie McGowan, Matthew DF McInnes, Philippa Middleton, Karel G Moons, Zachary Munn, Jane Noyes, Barbara Nußbaumer-Streit, Donald L Patrick, Tatiana Pereira-Cenci, Ba’ Pham, Bob Phillips, Dawid Pieper, Michelle Pollock, Daniel S Quintana, Drummond Rennie, Melissa L Rethlefsen, Hannah R Rothstein, Maroeska M Rovers, Rebecca Ryan, Georgia Salanti, Ian J Saldanha, Margaret Sampson, Nancy Santesso, Rafael Sarkis-Onofre, Jelena Savović, Christopher H Schmid, Kenneth F Schulz, Guido Schwarzer, Beverley J Shea, Paul G Shekelle, Farhad Shokraneh, Mark Simmonds, Nicole Skoetz, Sharon E Straus, Anneliese Synnot, Emily E Tanner-Smith, Brett D Thombs, Hilary Thomson, Alexander Tsertsvadze, Peter Tugwell, Tari Turner, Lesley Uttley, Jeffrey C Valentine, Matt Vassar, Areti Angeliki Veroniki, Meera Viswanathan, Cole Wayant, Paul Whaley, and Kehu Yang. We thank the following contributors who provided feedback on a preliminary version of the PRISMA 2020 checklist: Jo Abbott, Fionn Büttner, Patricia Correia-Santos, Victoria Freeman, Emily A Hennessy, Rakibul Islam, Amalia (Emily) Karahalios, Kasper Krommes, Andreas Lundh, Dafne Port Nascimento, Davina Robson, Catherine Schenck-Yglesias, Mary M Scott, Sarah Tanveer and Pavel Zhelnov. We thank Abigail H Goben, Melissa L Rethlefsen, Tanja Rombey, Anna Scott, and Farhad Shokraneh for their helpful comments on the preprints of the PRISMA 2020 papers. We thank Edoardo Aromataris, Stephanie Chang, Toby Lasserson and David Schriger for their helpful peer review comments on the PRISMA 2020 papers.

Contributors: JEM and DM are joint senior authors. MJP, JEM, PMB, IB, TCH, CDM, LS, and DM conceived this paper and designed the literature review and survey conducted to inform the guideline content. MJP conducted the literature review, administered the survey and analysed the data for both. MJP prepared all materials for the development meeting. MJP and JEM presented proposals at the development meeting. All authors except for TCH, JMT, EAA, SEB, and LAM attended the development meeting. MJP and JEM took and consolidated notes from the development meeting. MJP and JEM led the drafting and editing of the article. JEM, PMB, IB, TCH, LS, JMT, EAA, SEB, RC, JG, AH, TL, EMW, SM, LAM, LAS, JT, ACT, PW, and DM drafted particular sections of the article. All authors were involved in revising the article critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the article. MJP is the guarantor of this work. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: There was no direct funding for this research. MJP is supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE200101618) and was previously supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Fellowship (1088535) during the conduct of this research. JEM is supported by an Australian NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1143429). TCH is supported by an Australian NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (1154607). JMT is supported by Evidence Partners Inc. JMG is supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Health Knowledge Transfer and Uptake. MML is supported by The Ottawa Hospital Anaesthesia Alternate Funds Association and a Faculty of Medicine Junior Research Chair. TL is supported by funding from the National Eye Institute (UG1EY020522), National Institutes of Health, United States. LAM is supported by a National Institute for Health Research Doctoral Research Fellowship (DRF-2018-11-ST2-048). ACT is supported by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Synthesis. DM is supported in part by a University Research Chair, University of Ottawa. The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/conflicts-of-interest/ and declare: EL is head of research for the BMJ ; MJP is an editorial board member for PLOS Medicine ; ACT is an associate editor and MJP, TL, EMW, and DM are editorial board members for the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology ; DM and LAS were editors in chief, LS, JMT, and ACT are associate editors, and JG is an editorial board member for Systematic Reviews . None of these authors were involved in the peer review process or decision to publish. TCH has received personal fees from Elsevier outside the submitted work. EMW has received personal fees from the American Journal for Public Health , for which he is the editor for systematic reviews. VW is editor in chief of the Campbell Collaboration, which produces systematic reviews, and co-convenor of the Campbell and Cochrane equity methods group. DM is chair of the EQUATOR Network, IB is adjunct director of the French EQUATOR Centre and TCH is co-director of the Australasian EQUATOR Centre, which advocates for the use of reporting guidelines to improve the quality of reporting in research articles. JMT received salary from Evidence Partners, creator of DistillerSR software for systematic reviews; Evidence Partners was not involved in the design or outcomes of the statement, and the views expressed solely represent those of the author.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and the public were not involved in this methodological research. We plan to disseminate the research widely, including to community participants in evidence synthesis organisations.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

- Gurevitch J ,

- Koricheva J ,

- Nakagawa S ,

- Liberati A ,

- Tetzlaff J ,

- Altman DG ,

- PRISMA Group

- Tricco AC ,

- Sampson M ,

- Shamseer L ,

- Leoncini E ,

- de Belvis G ,

- Ricciardi W ,

- Fowler AJ ,

- Leclercq V ,

- Beaudart C ,

- Ajamieh S ,

- Rabenda V ,

- Tirelli E ,

- O’Mara-Eves A ,

- McNaught J ,

- Ananiadou S

- Marshall IJ ,

- Noel-Storr A ,

- Higgins JPT ,

- Chandler J ,

- McKenzie JE ,

- López-López JA ,

- Becker BJ ,

- Campbell M ,

- Sterne JAC ,

- Savović J ,

- Sterne JA ,

- Hernán MA ,

- Reeves BC ,

- Whiting P ,

- Higgins JP ,

- ROBIS group

- Hultcrantz M ,

- Stewart L ,

- Bossuyt PM ,

- Flemming K ,

- McInnes E ,

- France EF ,

- Cunningham M ,

- Rethlefsen ML ,

- Kirtley S ,

- Waffenschmidt S ,

- PRISMA-S Group

- ↵ Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions : Version 6.0. Cochrane, 2019. Available from https://training.cochrane.org/handbook .

- Dekkers OM ,

- Vandenbroucke JP ,

- Cevallos M ,

- Renehan AG ,

- ↵ Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JV, eds. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis. Russell Sage Foundation, 2019.

- IOM (Institute of Medicine)

- PRISMA-P Group

- Salanti G ,

- Caldwell DM ,

- Stewart LA ,

- PRISMA-IPD Development Group

- Zorzela L ,

- Ioannidis JP ,

- PRISMAHarms Group

- McInnes MDF ,

- Thombs BD ,

- and the PRISMA-DTA Group

- Beller EM ,

- Glasziou PP ,

- PRISMA for Abstracts Group

- Mayo-Wilson E ,

- Dickersin K ,

- MUDS investigators

- Stovold E ,

- Beecher D ,

- Noel-Storr A

- McGuinness LA

- Sarafoglou A ,

- Boutron I ,

- Giraudeau B ,

- Porcher R ,

- Chauvin A ,

- Schulz KF ,

- Schroter S ,

- Stevens A ,

- Weinstein E ,

- Macleod MR ,

- IICARus Collaboration

- Kirkham JJ ,

- Petticrew M ,

- Tugwell P ,

- PRISMA-Equity Bellagio group

The guidelines manual

NICE process and methods [PMG6] Published: 30 November 2012

- Tools and resources

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The scope

- 3 The Guideline Development Group

- 4 Developing review questions and planning the systematic review

- 5 Identifying the evidence: literature searching and evidence submission

6 Reviewing the evidence

- 7 Assessing cost effectiveness

- 8 Linking clinical guidelines to other NICE guidance

- 9 Developing and wording guideline recommendations

- 10 Writing the clinical guideline and the role of the NICE editors

- 11 The consultation process and dealing with stakeholder comments

- 12 Finalising and publishing the guideline

- 13 Implementation support for clinical guidelines

- 14 Updating published clinical guidelines and correcting errors

- Summary of main changes from the 2009 guidelines manual

- Update information

- About this manual

NICE process and methods

6.1 selecting relevant studies, 6.2 questions about interventions, 6.3 questions about diagnosis, 6.4 questions about prognosis, 6.5 using patient experience to inform review questions, 6.6 published guidelines, 6.7 further reading.

Studies identified during literature searches (see chapter 5 ) need to be reviewed to identify the most appropriate data to help address the review questions, and to ensure that the guideline recommendations are based on the best available evidence. A systematic review process should be used that is explicit and transparent. This involves five major steps:

writing the review protocol (see section 4.4 )

selecting relevant studies

assessing their quality

synthesising the results

interpreting the results.

The process of selecting relevant studies is common to all systematic reviews; the other steps are discussed below in relation to the major types of questions. The same rigour should be applied to reviewing fully and partially published studies, as well as unpublished data supplied by stakeholders.

The study selection process for clinical studies and economic evaluations should be clearly documented, giving details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria that were applied.

6.1.1 Clinical studies

Before acquiring papers for assessment, the information specialist or systematic reviewer should sift the evidence identified in the search in order to discard irrelevant material. First, the titles of the retrieved citations should be scanned and those that fall outside the topic of the guideline should be excluded. A quick check of the abstracts of the remaining papers should identify those that are clearly not relevant to the review questions and hence can be excluded.

Next, the remaining abstracts should be scrutinised against the inclusion and exclusion criteria agreed by the Guideline Development Group (GDG). Abstracts that do not meet the inclusion criteria should be excluded. Any doubts about inclusion should be resolved by discussion with the GDG before the results of the study are considered. Once the sifting is complete, full versions of the selected studies can be acquired for assessment. Studies that fail to meet the inclusion criteria once the full version has been checked should be excluded; those that meet the criteria can be assessed. Because there is always a potential for error and bias in selecting the evidence, double sifting (that is, sifting by two people) of a random selection of abstracts should be performed periodically (Edwards et al. 2002).

6.1.2 Conference abstracts

Conference abstracts can be a good source of information in systematic reviews. For example, conference abstracts can be important in pointing to published trials that may be missed, in estimating the amount of not-fully-published evidence (and hence guiding calls for evidence and judgements about publication bias), or in identifying ongoing trials that are due to be published. These sources of information are important in interpreting systematic reviews, and so conference abstracts should not be excluded in the search strategy.

However, the following should be considered when deciding whether to include conference abstracts as a source of evidence:

Conference abstracts on their own seldom have sufficient information to allow confident judgements to be made about the quality and results of a study.

It could be very time consuming to trace the original studies or additional data relating to the conference abstracts, and the information found may not always be useful.

If sufficient evidence has been identified from full published studies, it may be reasonable not to trace the original studies or additional data related to conference abstracts.

If there is a lack of or limited evidence identified from full published studies, the systematic reviewer may consider an additional process for tracing the original studies or additional data relating to the conference abstracts, in order to allow full critical appraisal and to make judgements on their inclusion in or exclusion from the systematic review.

6.1.3 Economic evaluations

The process for sifting and selecting economic evaluations for assessment is essentially the same as for clinical studies. Consultation between the information specialist, the health economist and the systematic reviewer is essential when deciding the inclusion criteria; these decisions should be discussed and agreed with the GDG. The review should be targeted to identify the papers that are most relevant to current NHS practice and hence likely to inform GDG decision-making. The review should also usually focus on 'full' economic evaluations that compare both the costs and health consequences of the alternative interventions and any services under consideration.

Inclusion criteria for filtering and selection of papers for review by the health economist should specify relevant populations and interventions for the review question. They should also specify the following:

An appropriate date range, as older studies may reflect outdated practices.

The country or setting, as studies conducted in other healthcare systems might not be relevant to the NHS. In some cases it may be appropriate to limit consideration to UK-based or OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) studies.

The type of economic evaluation. This may include cost–utility, cost–benefit, cost-effectiveness, cost-minimisation or cost–consequence analyses. Non-comparative costing studies, 'burden of disease' studies and 'cost of illness' studies should usually be excluded.

These questions concern the relative effects of an intervention, as described in section 4.3.1 . The consideration of cost effectiveness is integral to the process of reviewing evidence and making recommendations about interventions. However, the quality criteria and ways of summarising the data are slightly different from those for clinical effectiveness, so these are discussed in separate subsections.

6.2.1 Assessing study quality for clinical effectiveness

Study quality can be defined as the degree of confidence about the estimate of a treatment effect.

The first stage is to determine the study design so that the appropriate criteria can be applied in the assessment. A study design checklist can be obtained from the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Higgins and Green 2011). Tables 13.2.a and 13.2.b in the Cochrane handbook are lists of study design features for studies with allocation to interventions at the individual and group levels respectively, and box 13.4.a provides useful notes for completing the checklist.

Once a study has been classified, it should be assessed using the methodology checklist for that type of study (see appendices B–E ). To minimise errors and any potential bias in the assessment, two reviewers should independently assess the quality of a random selection of studies. Any differences arising from this should be discussed fully at a GDG meeting.

The quality of a study can vary depending on which of its measured outcomes is being considered. Well-conducted randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are more likely than non-randomised studies to produce similar comparison groups, and are therefore particularly suited to estimating the effects of interventions. However, short-term outcomes may be less susceptible to bias than long-term outcomes because of greater loss to follow-up with the latter. It is therefore important when summarising evidence that quality is considered according to outcome.

6.2.1.1 The GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach to assessing the quality of evidence

The GRADE approach for questions about interventions has been used in the development of NICE clinical guidelines since 2009. For more details about GRADE, see the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology series, appendix K and the GRADE working group website .

GRADE is a system developed by an international working group for rating the quality of evidence across outcomes in systematic reviews and guidelines; it can also be used to grade the strength of recommendations in guidelines. The system is designed for reviews and guidelines that examine alternative management strategies or interventions, and these may include no intervention or current best management. The key difference from other assessment systems is that GRADE rates the quality of evidence for a particular outcome across studies and does not rate the quality of individual studies.

In order to apply GRADE, the evidence must clearly specify the relevant setting, population, intervention, comparator(s) and outcomes.

Before starting an evidence review, the GDG should apply an initial rating to the importance of outcomes, in order to identify which outcomes of interest are both 'critical' to decision-making and 'important' to patients. This rating should be confirmed or, if absolutely necessary, revised after completing the evidence review.

Box 6.1 summarises the GRADE approach to rating the quality of evidence.

Box 6.1 The GRADE approach to assessing the quality of evidence for intervention studies

The approach taken by NICE differs from the standard GRADE system in two ways:

It also integrates a review of the quality of cost-effectiveness studies.

It has no 'overall summary' labels for the quality of the evidence across all outcomes or for the strength of a recommendation, but uses the wording of recommendations to reflect the strength of the recommendation (see section 9.3.3 ).

6.2.2 Summarising and presenting results for clinical effectiveness

Characteristics of data should be extracted to a standard template for inclusion in an evidence table (see appendix J1 ). Evidence tables help to identify the similarities and differences between studies, including the key characteristics of the study population and interventions or outcome measures. This provides a basis for comparison.

Meta-analysis may be needed to pool treatment estimates from different studies. Recognised approaches to meta-analysis should be used, as described in the manual from NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2009) and in Higgins and Green (2011).

The body of evidence addressing a question should then be presented within the text of the full guideline as an evidence profile as described in the GRADE system (see appendix K ). GRADEpro software can be used to prepare these profiles. Evidence profiles contain a 'quality assessment' section that summarises the quality of the evidence and a 'summary of findings' section that presents the outcome data for each critical and each important clinical outcome. The 'summary of findings' section includes a limited description of the quality of the evidence and can be presented alone in the text of the guideline (in which case full GRADE profiles should be presented in an appendix).

Short evidence statements for outcomes should be presented after the GRADE profiles, summarising the key features of the evidence on clinical effectiveness (including adverse events as appropriate) and cost effectiveness. The evidence statements should include the number of studies and participants, the quality of the evidence and the direction of estimate of the effect (see box 6.2 for examples of evidence statements). An evidence statement may be needed even if no evidence is identified for a critical or important outcome. Evidence statements may also note the presence of relevant ongoing research.

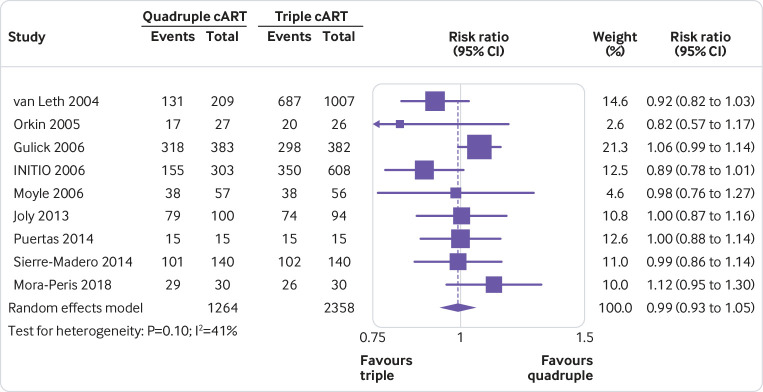

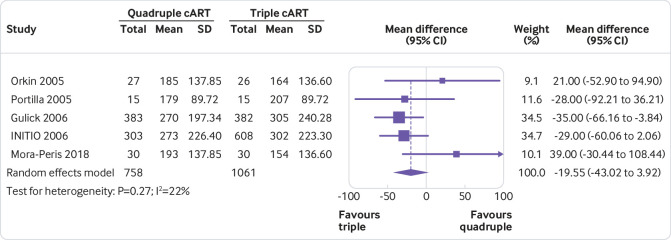

Box 6.2 Examples of evidence statements

6.2.3 indirect treatment comparisons and mixed treatment comparisons.

NICE has a preference for data from head-to-head RCTs, and these should be presented in the reference case analysis if available. However, there may be situations when data from head-to-head studies of the options (and/or comparators) of interest are not available. In these circumstances, indirect treatment comparison analyses should be considered.

An 'indirect treatment comparison' refers to the synthesis of data from trials in which the interventions of interest have been compared indirectly using data from a network of trials that compare the interventions with other interventions. A 'mixed treatment comparison' refers to an analysis that includes both trials that compare the interventions of interest head-to-head and trials that compare them indirectly.

The principles of good practice for systematic reviews and meta-analyses should be carefully followed when conducting indirect treatment comparisons or mixed treatment comparisons. The rationale for identifying and selecting the RCTs should be explained, including the rationale for selecting the treatment comparisons that have been included. A clear description of the methods of synthesis is required. The methods and results of the individual trials should be documented. If there is doubt about the relevance of particular trials, a sensitivity analysis in which these trials are excluded should also be presented. The heterogeneity between the results of pairwise comparisons and inconsistencies between the direct and indirect evidence on the interventions should be reported.

There may be circumstances in which data from head-to-head RCTs are less than ideal (for example, the sample size may be small or there may be concerns about the external validity). In such cases, additional evidence from mixed treatment comparisons can be considered. In these cases, mixed treatment comparisons should be presented separately from the reference-case analysis and a rationale for their inclusion provided. Again, the principles of good practice apply.

When multiple options are being appraised, data from RCTs (when available) that compare each of the options head-to-head should be presented in a series of pairwise comparisons. Consideration may be given to presenting an additional analysis using a mixed treatment comparison framework.

When evidence is combined using indirect or mixed treatment comparison frameworks, trial randomisation should be preserved. A comparison of the results from single treatment arms from different randomised trials is not acceptable unless the data are treated as observational and appropriate steps are taken to adjust for possible bias and increased uncertainty.

Analyses using indirect or mixed treatment comparison frameworks may include comparator interventions (including placebo) that have not been defined in the scope of the guideline if they are relevant to the development of the network of evidence. The rationale for the inclusion and exclusion of comparator interventions should be clearly reported. Again, the principles of good practice apply.

Evidence from a mixed treatment comparison can be presented in a variety of ways. The network of evidence can be presented as tables. It may also be presented diagrammatically as long as the direct and indirect treatment comparisons are clearly identified and the number of trials in each comparison is stated.

If sufficient relevant and valid data are not available to include in meta-analyses of head-to-head trials, or mixed or indirect treatment comparisons, the analysis may have to be restricted to a qualitative overview that critically appraises individual studies and presents their results. The results of this type of analysis should be approached with particular caution.

Further information on evidence synthesis is provided by the technical support documents developed by the NICE Decision Support Unit (DSU) .

6.2.4 Assessing study quality for cost effectiveness

Estimates of resource use obtained from clinical studies should be treated like other clinical outcomes and reviewed using the processes described above. Reservations about the applicability of these estimates to routine NHS practice should be noted in the economics evidence profile, in the same way as in a GRADE profile (see section 6.2.1.1 ), and taken into consideration by the GDG.

However, the criteria for appraising other economic estimates – such as costs, cost-effectiveness ratios and net benefits – are rather different, because these estimates are usually obtained using some form of modelling. In addition to formal decision-analytic models, this includes economic evaluations conducted alongside clinical trials. These usually require some external sources of information (for example, unit costs, health-state valuations or long-term prognostic data) and estimation procedures to predict long-term costs and outcomes. These considerations also apply to relatively simple cost calculations based on expert judgement or on observed resource use and unit cost data.

All economic estimates used to inform guideline recommendations should be appraised using the methodology checklist for economic evaluations ( appendix G ). This should be used to appraise unpublished economic evaluations, such as studies submitted by stakeholders and academic papers that are not yet published, as well as published papers. The same criteria should be applied to any new economic evaluations conducted for the guideline (see chapter 7 ).

The checklist ( appendix G ) includes a section on the applicability of the study to the specific question and the context for NICE decision-making (analogous to the GRADE 'directness' criterion). This checklist is designed to determine whether an economic evaluation provides evidence that is useful to inform GDG decision-making, analogous to the assessment of study limitations in GRADE.

The checklist includes an overall judgement on the applicability of the study to the guideline context, as follows:

Directly applicable – the study meets all applicability criteria, or fails to meet one or more applicability criteria but this is unlikely to change the conclusions about cost effectiveness.

Partially applicable – the study fails to meet one or more applicability criteria, and this could change the conclusions about cost effectiveness.

Not applicable – the study fails to meet one or more applicability criteria, and this is likely to change the conclusions about cost effectiveness. Such studies would usually be excluded from further consideration.

The checklist also includes an overall summary judgement on the methodological quality of economic evaluations, as follows:

Minor limitations – the study meets all quality criteria, or fails to meet one or more quality criteria but this is unlikely to change the conclusions about cost effectiveness.

Potentially serious limitations – the study fails to meet one or more quality criteria, and this could change the conclusions about cost effectiveness.

Very serious limitations – the study fails to meet one or more quality criteria, and this is highly likely to change the conclusions about cost effectiveness. Such studies should usually be excluded from further consideration.

The robustness of the study results to methodological limitations may sometimes be apparent from reported sensitivity analyses. If not, judgement will be needed to assess whether a limitation would be likely to change the results and conclusions.

If necessary, the health technology assessment checklist for decision-analytic models (Philips et al. 2004) may also be used to give a more detailed assessment of the methodological quality of modelling studies.

The judgements that the health economist makes using the checklist for economic evaluations (and the health technology assessment modelling checklist, if appropriate) should be recorded and presented in an appendix to the full guideline. The 'comments' column in the checklist should be used to record reasons for these judgements, as well as additional details about the studies where necessary.

6.2.5 Summarising and presenting results for cost effectiveness

Cost, cost effectiveness or net benefit estimates from published or unpublished studies, or from economic analyses conducted for the guideline, should be presented in an 'economic evidence profile' adapted from the GRADE profile (see appendix K ). Whenever a GRADE profile is presented in the full version of a NICE clinical guideline, it should be accompanied by relevant economic information (resource use, costs, cost effectiveness and/or net benefit estimates as appropriate). It should be explicitly stated if economic information is not available or if it is not thought to be relevant to the question.

The economic evidence profile includes columns for the overall assessments of study limitations and applicability described above. There is also a comments column where the health economist can note any particular issues that the GDG should consider when assessing the economic evidence. Footnotes should be used to explain the reasons for quality assessments, as in the standard GRADE profile.

The results of the economic evaluations included should be presented in the form of a best-available estimate or range for the incremental cost, the incremental effect and, where relevant, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio or net benefit estimate. A summary of the extent of uncertainty about the estimates should also be presented in the economic evidence profile. This should reflect the results of deterministic or probabilistic sensitivity analyses or stochastic analyses of trial data, as appropriate.

Each economic evaluation included should usually be presented in a separate row of the economic evidence profile. If large numbers of economic evaluations of sufficiently high quality and applicability are available, a single row could be used to summarise a number of studies based on shared characteristics; this should be explicitly justified in a footnote.

Inconsistency between the results of economic evaluations will be shown by differences between rows of the economic evidence profile (a separate column examining 'consistency' is therefore unnecessary). The GDG should consider the implications of any unexplained differences between model results when assessing the body of clinical and economic evidence and drawing up recommendations. This includes clearly explaining the GDG's preference for certain results when forming recommendations.

If results are available for two or more patient subgroups, these should be presented in separate economic evidence profile tables or as separate rows within a single table.

Costs and cost-effectiveness estimates should be presented only for the appropriate incremental comparisons – where an intervention is compared with the next most expensive non-dominated option (a clinical strategy is said to 'dominate' the alternatives when it is both more effective and less costly; see section 7.3 ). If comparisons are relevant only for some groups of the population (for example, patients who cannot tolerate one or more of the other options, or for whom one or more of the options is contraindicated), this should be stated in a footnote to the economic evidence profile table.

A short evidence statement should be presented alongside the GRADE and economic evidence profile tables, summarising the key features of the evidence on clinical and cost effectiveness.

Questions about diagnosis are concerned with the performance of a diagnostic test or test strategy (see section 4.3.2 ). Note that 'test and treat' studies (in which the outcomes of patients who undergo a new diagnostic test in combination with a management strategy are compared with the outcomes of patients who receive the usual diagnostic test and management strategy) should be addressed in the same way as intervention studies (see section 6.2 ).

6.3.1 Assessing study quality

Studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be assessed using the methodology checklist for QUADAS-2 (Quality Assessment of Studies of Diagnostic Accuracy included in Systematic Reviews) ( appendix F ). Characteristics of data should be extracted to a standard template for inclusion in an evidence table (see appendix J2 ). Questions relating to diagnostic test accuracy are usually best answered by cross-sectional studies. Case–control studies can also be used, but these are more prone to bias and often result in inflated estimates of diagnostic test accuracy.

There is currently a lack of empirical evidence about the size and direction of bias contributed by specific aspects of the design and conduct of studies on diagnostic test accuracy. Making judgements about the overall quality of studies can therefore be difficult. Before starting the review, an assessment should be made to determine which quality appraisal criteria (from the QUADAS-2 checklist) are likely to be the most important indicators of quality for the particular question about diagnostic test accuracy being addressed. These criteria will be useful in guiding decisions about the overall quality of individual studies and whether to exclude certain studies, and when summarising and presenting the body of evidence for the question about diagnostic test accuracy as a whole (see section 6.3.2). Clinical input (for example, from a GDG member) may be needed to identify the most appropriate quality criteria.

6.3.2 Summarising and presenting results

No well designed and validated approach currently exists for summarising a body of evidence for studies on diagnostic test accuracy. In the absence of such a system, a narrative summary of the quality of the evidence should be given, based on the quality appraisal criteria from QUADAS-2 ( appendix F ) that were considered to be most important for the question being addressed (see section 6.3.1).

Numerical summaries of diagnostic test accuracy may be presented as tables to help summarise the available evidence. Meta-analysis of such estimates from different studies is possible, but is not widely used. If this is attempted, relevant published technical advice should be used to guide reviewers.

Numerical summaries and analyses should be followed by a short evidence statement summarising what the evidence shows.

These questions are described in section 4.3.3 .

6.4.1 Assessing study quality

Studies that are reviewed for questions about prognosis should be assessed using the methodology checklist for prognostic studies ( appendix I ). There is currently a lack of empirical evidence about the size and direction of bias contributed by specific aspects of the design and conduct of studies on prognosis. Making judgements about the overall quality of studies can therefore be difficult. Before starting the review, an assessment should be made to determine which quality appraisal criteria (from the checklist in appendix I ) are likely to be the most important indicators of quality for the particular question about prognosis being addressed. These criteria will be useful in guiding decisions about the overall quality of individual studies and whether to exclude certain studies, and when summarising and presenting the body of evidence for the question about prognosis as a whole (see section 6.4.2). Clinical input (for example, from a GDG member) may be needed to identify the most appropriate quality criteria.

6.4.2 Summarising and presenting results

No well designed and validated approach currently exists for summarising a body of evidence for studies on prognosis. A narrative summary of the quality of the evidence should therefore be given, based on the quality appraisal criteria from appendix I that were considered to be most important for the question being addressed (see section 6.4.1). Characteristics of data should be extracted to a standard template for inclusion in an evidence table (see appendix J3 ).

Results from the studies included may be presented as tables to help summarise the available evidence. Reviewers should be wary of using meta-analysis as a tool to summarise large observational studies, because the results obtained may give a spurious sense of confidence in the study results.

The narrative summary should be followed by a short evidence statement summarising what the evidence shows.

These questions are described in section 4.3.4 .

6.5.1 Assessing study quality

Studies about patient experience are likely to be qualitative studies or cross-sectional surveys. Qualitative studies should be assessed using the methodology checklist for qualitative studies ( appendix H ). It is important to consider which quality appraisal criteria from this checklist are likely to be the most important indicators of quality for the specific research question being addressed. These criteria may be helpful in guiding decisions about the overall quality of individual studies and whether to exclude certain studies, and when summarising and presenting the body of evidence for the research question about patient experience as a whole.

There is no methodology checklist for the quality appraisal of cross-sectional surveys. Such surveys should be assessed for the rigour of the process used to develop the questions and their relevance to the population under consideration, and for the existence of significant bias (for example, non-response bias).

6.5.2 Summarising and presenting results

A description of the quality of the evidence should be given, based on the quality appraisal criteria from appendix H that were considered to be the most important for the research question being addressed. If appropriate, the quality of the cross-sectional surveys included should also be summarised.

Consider presenting the quality assessment of included studies in tables (see table 1 in appendix H for an example). Methods to synthesise qualitative studies (for example, meta-ethnography) are evolving, but the routine use of such methods in guidelines is not currently recommended.

The narrative summary should be followed by a short evidence statement summarising what the evidence shows. Characteristics of data should be extracted to a standard template for inclusion in an evidence table (see appendix J4 ).

Relevant published guidelines from other organisations may be identified in the search for evidence. These should be assessed for quality using the AGREE II [ 10 ] (Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation II) instrument (Brouwers et al. 2010) to ensure that they have sufficient documentation to be considered. There is no cut-off point for accepting or rejecting a guideline, and each GDG will need to set its own parameters. These should be documented in the methods section of the full guideline, along with a summary of the assessment. The results should be presented as an appendix to the full guideline.

Reviews of evidence from other guidelines that cover questions formulated by the GDG may be considered as evidence if:

they are assessed using the appropriate methodology checklist from this manual and are judged to be of high quality

they are accompanied by an evidence statement and evidence table(s)

the evidence is updated according to the methodology for exceptional updates of NICE clinical guidelines (see section 14.4 ).

The GDG should create its own evidence summaries or statements. Evidence tables from other guidelines should be referenced with a direct link to the source website or a full reference of the published document. The GDG should formulate its own recommendations, taking into consideration the whole body of evidence.

Recommendations from other guidelines should not be quoted verbatim, except for recommendations from NHS policy or legislation (for example, Health and Social Care Act 2008).

Altman DG (2001) Systematic reviews of evaluations of prognostic variables. British Medical Journal 323: 224–8

Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ et al. (2011) GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64: 401–6

Brouwers M, Kho ME, Browman GP et al. for the AGREE Next Steps Consortium (2010) AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare . Canadian Medical Association Journal 182: E839–42

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2009) Systematic reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care . University of York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

Chiou CF, Hay JW, Wallace JF et al. (2003) Development and validation of a grading system for the quality of cost-effectiveness studies. Medical Care 41: 32–44

Drummond MF, O'Brien B, Stoddart GL et al. (1997) Critical assessment of economic evaluation. In: Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes, 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications

Eccles M, Mason J (2001) How to develop cost-conscious guidelines. Health Technology Assessment 5: 1–69

Edwards P, Clarke M, DiGuiseppi C et al. (2002) Identification of randomized trials in systematic reviews: accuracy and reliability of screening records. Statistics in Medicine 21: 1635–40

Evers SMAA, Goossens M, de Vet H et al. (2005) Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: Consensus on Health Economic Criteria. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 21: 240–5

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ et al. (2011) GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64: 380–2

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Akl EA et al. (2011) GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction – GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64: 383–94

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al. (2011) GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64: 395–400

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G et al. (2011) GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence – study limitations (risk of bias). Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64: 407–15

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Montori V et al. (2011) GRADE guidelines 5: Rating the quality of evidence – publication bias. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64: 1277–82

Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al. (2011) GRADE guidelines 6: Rating the quality of evidence – imprecision. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64: 1283–93

Guyatt GH, Oxmand AD, Kunz R et al. (2011) GRADE guidelines 7: Rating the quality of evidence – inconsistency. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64: 1294–302

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al. (2011) GRADE guidelines 8: Rating the quality of evidence – indirectness. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64: 1303–10

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Sultan S et al. (2011) GRADE guidelines 9: Rating up the quality of evidence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64: 1311–6

Harbord RM, Deeks JJ, Egger M et al. (2007) A unification of models for meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Biostatistics 8: 239–51

Higgins JPT, Green S, editors (2011) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011) [online]

Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J et al. (2003) Systematic reviews to support evidence-based medicine. How to review and apply findings of healthcare research. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press

Oxman AD, Guyatt GH (1992) A consumer's guide to subgroup analyses. Annals of Internal Medicine 116: 78–84

Philips Z, Ginnelly L, Sculpher M et al. (2004) Review of guidelines for good practice in decision-analytic modelling in health technology assessment. Health Technology Assessment 8: iii–iv, ix–xi, 1–158

Schünemann HJ, Best D, Vist G et al. for the GRADE Working Group (2003) Letters, numbers, symbols and words: how to communicate grades of evidence and recommendations. Canadian Medical Association Journal 169: 677–80

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J et al. for the GRADE Working Group (2008) Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. British Medical Journal 336: 1106–10

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (2008) SIGN 50. A guideline developer's handbook, revised edition, January. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network

Sharp SJ, Thompson SG (2000) Analysing the relationship between treatment effect and underlying risk in meta-analysis: comparison and development of approaches. Statistics in Medicine 19: 3251–74

Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME et al. and the QUADAS-2 group (2011) QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Annals of Internal Medicine 155: 529–36

[ 10 ] For more details about AGREE II, see the AGREE Enterprise website .

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews

Matthew j page, david moher, patrick m bossuyt, isabelle boutron, tammy c hoffmann, cynthia d mulrow, larissa shamseer, jennifer m tetzlaff, sue e brennan, julie glanville, jeremy m grimshaw, asbjørn hróbjartsson, manoj m lalu, tianjing li, elizabeth w loder, evan mayo-wilson, steve mcdonald, luke a mcguinness, lesley a stewart, james thomas, andrea c tricco, vivian a welch, penny whiting, joanne e mckenzie.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence to: M Page [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Accepted 2021 Jan 4; Collection date 2021.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

The methods and results of systematic reviews should be reported in sufficient detail to allow users to assess the trustworthiness and applicability of the review findings. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement was developed to facilitate transparent and complete reporting of systematic reviews and has been updated (to PRISMA 2020) to reflect recent advances in systematic review methodology and terminology. Here, we present the explanation and elaboration paper for PRISMA 2020, where we explain why reporting of each item is recommended, present bullet points that detail the reporting recommendations, and present examples from published reviews. We hope that changes to the content and structure of PRISMA 2020 will facilitate uptake of the guideline and lead to more transparent, complete, and accurate reporting of systematic reviews.

Systematic reviews are essential for healthcare providers, policy makers, and other decision makers, who would otherwise be confronted by an overwhelming volume of research on which to base their decisions. To allow decision makers to assess the trustworthiness and applicability of review findings, reports of systematic reviews should be transparent and complete. Furthermore, such reporting should allow others to replicate or update reviews. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement published in 2009 (hereafter referred to as PRISMA 2009) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 was designed to help authors prepare transparent accounts of their reviews, and its recommendations have been widely endorsed and adopted. 13 We have updated the PRISMA 2009 statement (to PRISMA 2020) to ensure currency and relevance and to reflect advances in systematic review methodology and terminology.

Summary points.

The PRISMA 2020 statement includes a checklist of 27 items to guide reporting of systematic reviews