Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.4 Doing Research on Social Problems

Learning objectives.

- List the major advantages and disadvantages of surveys, observational studies, and experiments.

- Explain why scholars who study social problems often rely on existing data.

Sound research is an essential tool for understanding the sources, dynamics, and consequences of social problems and possible solutions to them. This section briefly describes the major ways in which sociologists gather information about social problems. Table 1.2 “Major Sociological Research Methods” summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of each method.

Table 1.2 Major Sociological Research Methods

The survey is the most common method by which sociologists gather their data. The Gallup poll is perhaps the most well-known example of a survey and, like all surveys, gathers its data with the help of a questionnaire that is given to a group of respondents . The Gallup poll is an example of a survey conducted by a private organization, but sociologists do their own surveys, as does the government and many organizations in addition to Gallup. Many surveys are administered to respondents who are randomly chosen and thus constitute a random sample . In a random sample, everyone in the population (whether it be the whole US population or just the population of a state or city, all the college students in a state or city or all the students at just one college, etc.) has the same chance of being included in the survey. The beauty of a random sample is that it allows us to generalize the results of the sample to the population from which the sample comes. This means that we can be fairly sure of the behavior and attitudes of the whole US population by knowing the behavior and attitudes of just four hundred people randomly chosen from that population.

Some surveys are face-to-face surveys, in which interviewers meet with respondents to ask them questions. This type of survey can yield much information, because interviewers typically will spend at least an hour asking their questions, and a high response rate (the percentage of all people in the sample who agree to be interviewed), which is important to be able to generalize the survey’s results to the entire population. On the downside, this type of survey can be very expensive and time consuming to conduct.

Surveys are very useful for gathering various kinds of information relevant to social problems. Advances in technology have made telephone surveys involving random-digit dialing perhaps the most popular way of conducting a survey.

plantronicsgermany – Encore520 call center man standing – CC BY-ND 2.0.

Because of these drawbacks, sociologists and other researchers have turned to telephone surveys. Most Gallup polls are conducted over the telephone. Computers do random-digit dialing, which results in a random sample of all telephone numbers being selected. Although the response rate and the number of questions asked are both lower than in face-to-face surveys (people can just hang up the phone at the outset or let their answering machine take the call), the ease and low expense of telephone surveys are making them increasingly popular. Surveys done over the Internet are also becoming more popular, as they can reach many people at very low expense. A major problem with web surveys is that their results cannot necessarily be generalized to the entire population because not everyone has access to the Internet.

Surveys are used in the study of social problems to gather information about the behavior and attitudes of people regarding one or more problems. For example, many surveys ask people about their use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs or about their experiences of being unemployed or in poor health. Many of the chapters in this book will present evidence gathered by surveys carried out by sociologists and other social scientists, various governmental agencies, and private research and public interest firms.

Experiments

Experiments are the primary form of research in the natural and physical sciences, but in the social sciences they are for the most part found only in psychology. Some sociologists still use experiments, however, and they remain a powerful tool of social research.

The major advantage of experiments, whether they are done in the natural and physical sciences or in the social sciences, is that the researcher can be fairly sure of a cause-and-effect relationship because of the way the experiment is set up. Although many different experimental designs exist, the typical experiment consists of an experimental group and a control group , with subjects randomly assigned to either group. The researcher does something to the experimental group that is not done to the control group. If the two groups differ later in some variable, then it is safe to say that the condition to which the experimental group was subjected was responsible for the difference that resulted.

Most experiments take place in the laboratory, which for psychologists may be a room with a one-way mirror, but some experiments occur in the field, or in a natural setting ( field experiments ). In Minneapolis, Minnesota, in the early 1980s, sociologists were involved in a much-discussed field experiment sponsored by the federal government. The researchers wanted to see whether arresting men for domestic violence made it less likely that they would commit such violence again. To test this hypothesis, the researchers had police do one of the following after arriving at the scene of a domestic dispute: They either arrested the suspect, separated him from his wife or partner for several hours, or warned him to stop but did not arrest or separate him. The researchers then determined the percentage of men in each group who committed repeated domestic violence during the next six months and found that those who were arrested had the lowest rate of recidivism, or repeat offending (Sherman & Berk, 1984). This finding led many jurisdictions across the United States to adopt a policy of mandatory arrest for domestic violence suspects. However, replications of the Minneapolis experiment in other cities found that arrest sometimes reduced recidivism for domestic violence but also sometimes increased it, depending on which city was being studied and on certain characteristics of the suspects, including whether they were employed at the time of their arrest (Sherman, 1992).

As the Minneapolis study suggests, perhaps the most important problem with experiments is that their results are not generalizable beyond the specific subjects studied. The subjects in most psychology experiments, for example, are college students, who obviously are not typical of average Americans: They are younger, more educated, and more likely to be middle class. Despite this problem, experiments in psychology and other social sciences have given us very valuable insights into the sources of attitudes and behavior. Scholars of social problems are increasingly using field experiments to study the effectiveness of various policies and programs aimed at addressing social problems. We will examine the results of several such experiments in the chapters ahead.

Observational Studies

Observational research, also called field research , is a staple of sociology. Sociologists have long gone into the field to observe people and social settings, and the result has been many rich descriptions and analyses of behavior in juvenile gangs, bars, urban street corners, and even whole communities.

Observational studies consist of both participant observation and nonparticipant observation . Their names describe how they differ. In participant observation, the researcher is part of the group that she or he is studying, spends time with the group, and might even live with people in the group. Several classical social problems studies of this type exist, many of them involving people in urban neighborhoods (Liebow, 1967; Liebow, 1993; Whyte, 1943). In nonparticipant observation, the researcher observes a group of people but does not otherwise interact with them. If you went to your local shopping mall to observe, say, whether people walking with children looked happier than people without children, you would be engaging in nonparticipant observation.

Similar to experiments, observational studies cannot automatically be generalized to other settings or members of the population. But in many ways they provide a richer account of people’s lives than surveys do, and they remain an important method of research on social problems.

Existing Data

Sometimes sociologists do not gather their own data but instead analyze existing data that someone else has gathered. The US Census Bureau, for example, gathers data on all kinds of areas relevant to the lives of Americans, and many sociologists analyze census data on such social problems as poverty, unemployment, and illness. Sociologists interested in crime and the criminal justice system may analyze data from court records, while medical sociologists often analyze data from patient records at hospitals. Analysis of existing data such as these is called secondary data analysis . Its advantage to sociologists is that someone else has already spent the time and money to gather the data. A disadvantage is that the data set being analyzed may not contain data on all the topics in which a sociologist may be interested or may contain data on topics that are not measured in ways the sociologist might prefer.

The Scientific Method and Objectivity

This section began by stressing the need for sound research in the study of social problems. But what are the elements of sound research? At a minimum, such research should follow the rules of the scientific method . As you probably learned in high school and/or college science classes, these rules—formulating hypotheses, gathering and testing data, drawing conclusions, and so forth—help guarantee that research yields the most accurate and reliable conclusions possible.

An overriding principle of the scientific method is that research should be conducted as objectively as possible. Researchers are often passionate about their work, but they must take care not to let the findings they expect and even hope to uncover affect how they do their research. This in turn means that they must not conduct their research in a manner that helps achieve the results they expect to find. Such bias can happen unconsciously, and the scientific method helps reduce the potential for this bias as much as possible.

This potential is arguably greater in the social sciences than in the natural and physical sciences. The political views of chemists and physicists typically do not affect how an experiment is performed and how the outcome of the experiment is interpreted. In contrast, researchers in the social sciences, and perhaps particularly in sociology, often have strong feelings about the topics they are studying. Their social and political beliefs may thus influence how they perform their research on these topics and how they interpret the results of this research. Following the scientific method helps reduce this possible influence.

Key Takeaways

- The major types of research on social problems include surveys, experiments, observational studies, and the use of existing data.

- Surveys are the most common method, and the results of surveys of random samples may be generalized to the populations from which the samples come.

- Observation studies and existing data are also common methods in social problems research. Observation studies enable the gathering of rich, detailed information, but their results cannot necessarily be generalized beyond the people studied.

- Research on social problems should follow the scientific method to yield the most accurate and objective conclusions possible.

For Your Review

- Have you ever been a respondent or subject in any type of sociological or psychological research project? If so, how did it feel to be studied?

- Which type of social problems research method sounds most interesting to you? Why?

Liebow, E. (1967). Tally’s corner . Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

Liebow, E. (1993). Tell them who I am: The lives of homeless women . New York, NY: Free Press.

Sherman, L. W., & Berk, R. A. (1984). The specific deterrent effects of arrest for domestic assault. American Sociological Review, 49 , 261–272.

Sherman, L. W. (1992). Policing domestic violence: Experiments and dilemmas . New York, NY: Free Press.

Whyte, W. F. (1943). Street corner society: The social structure of an Italian slum . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Social Problems Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

2.4 Research Methods for Social Problems

Theories discuss the why of particular social problems. They begin to systematically explain, for example, why socioeconomic class is prevalent in industrialized societies, or why implicit bias is so common. But how do sociologists develop the theories in the first place or figure out if the theories are useful? For that, they must observe people interacting, and collect data. The ways in which social scientists collect, analyze, and understand research information are called research methods.

However, science isn’t the only way to understand the world. You may experience many more ways of knowing. When you consider why you know something, this knowledge may be based on different sources or experiences. You may know when the movie starts because a friend told you, or because you looked it up on Google. You may know that rain is currently falling because you feel it on your head. You may know that it is wrong to kill another person because it is a belief in your religious tradition or part of your own ethical understanding. You may know because you have a gut feeling that a situation is dangerous, or a choice is the right one. You may know that your friend will be late to class because past experience predicts it. Or, instead of the past, you can imagine the future, knowing that eating a hamburger will satisfy your hunger, just by seeing the picture on the menu. Finally, you may know something because the language you use supports you in noticing particular details. For example, how many ways can you describe the water that falls from the sky? People who live in Oregon, for instance, use several distinct words for rainy weather: drizzle, downpour, showers. Partly cloudy doesn’t change their plans, but they may throw a jacket in the car. In other regions, it may be more useful to describe snow or heat in great detail. The formation of language itself structures how you know something. The table in figure 2.23 organizes these ways of knowing.

Figure 2.23 Ways of Knowing and Examples

Each of these ways of knowing is useful, depending on the circumstances. For example, when my wife and I bought our house, we did research on home prices, home loans, and market value—reason. We talked about what home felt like to us—emotion. We walked through houses and pictured what life would look like in a particular house—imagination. Ultimately, when we drove down the cedar and fir-lined driveway, welcomed by the warm light through the window—sense perception—we turned to each other and said, “I hope this house is still for sale,” because we both knew we had found our home—intuition.

Of all of these ways of knowing, though, reason allows us to use logic and evidence to draw conclusions about what is true. Reason, as used in science, is unique among all of the ways of knowing because it allows us to propose an idea about how a social situation might work, observe the situation, and find out whether our idea is correct. Sociology is a unique scientific approach to understanding people. Let’s explore this more deeply.

As you saw in Chapter 1, sociology is the systematic study of society and social interactions to understand our social world. Although sages, leaders, philosophers, and other wisdom holders have asked what makes a good life throughout human history, sociology applies scientific principles to understanding human behavior.

Like anthropologists, psychologists, and other social scientists, sociologists collect and analyze data in order to draw conclusions about human behavior. Although these fields often overlap and complement each other, sociologists focus most on the interaction of people in groups, communities, institutions, and interrelated systems.

More simply, sociologists study society, a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture. Sociologists study human interactions at the smallest micro unit of how parents and children bond, to the widest macro lens of what causes war throughout recorded history. They explore microaggressions, those small moments of interaction that reinforce prejudice in small but powerful ways. They also study the generationally persistent systems of systemic inequality. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to rage and the climate crisis worsens, sociologists turn even greater attention to global and planetary systems to understand and explain our interdependence.

2.4.1 The Scientific Method

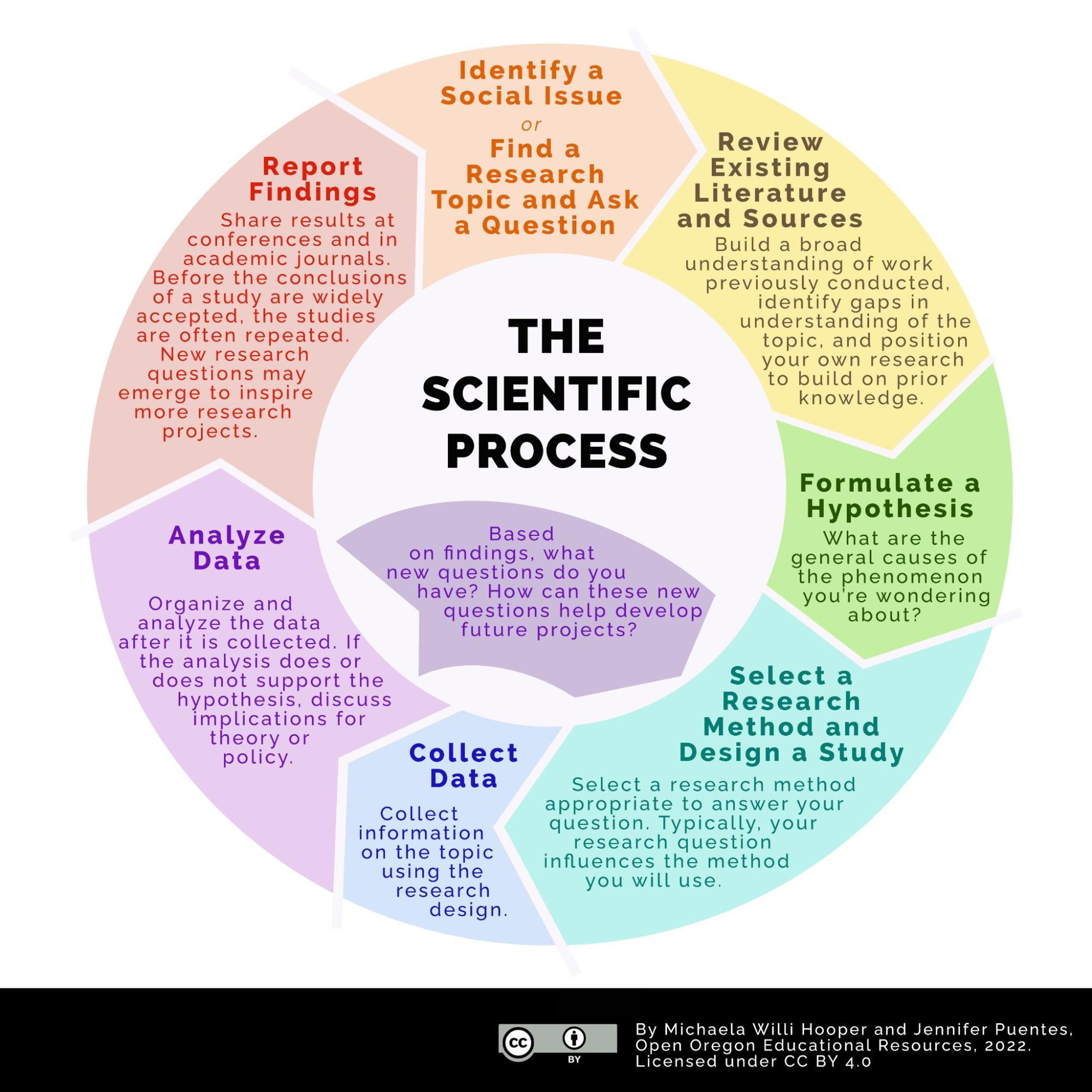

Scientists use shared approaches for figuring out how the social world works. The most common method is known as the scientific method , an established scholarly research process that involves asking a question, researching existing sources, forming a hypothesis, designing a data collection method, gathering data, and drawing conclusions. Often this method is shown as a straight line. Scientists proceed in an orderly fashion, executing one step after the next.

In reality, the scientific method is a circular process rather than a straight line, as shown in figure 2.24. The circle helps us to see that science is driven by curiosity and that learnings at each step move us to the next step, in ongoing loops. This model allows for the creativity and collaboration that is essential in how we actually create new scientific understandings. Let’s dive deeper!

Figure 2.24 The Scientific method as an ongoing process Figure 2.24 Image Description

2.4.1.1 Step 1: Identify a Social Issue/Find a Research Topic and Ask a Question

The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, select a problem, and identify the specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within a geographic location and time frame. “Are societies capable of sustained happiness?” would be too vague. The question should also be broad enough to be of significance. “What do personal hygiene habits reveal about the values of students at XYZ High School?” would be too narrow. Sociologists strive to frame questions that examine well-defined patterns and relationships.

2.4.1.2 Step 2: Review the Literature/Research Existing Sources

The next step researchers undertake is to conduct background research through a literature review, which is a review of any existing similar or related studies. A visit to the library, a thorough online search, and a survey of academic journals will uncover existing research about the topic of study. This step helps researchers gain a broad understanding of work previously conducted, identify gaps in understanding of the topic, and position their own research to build on prior knowledge. Researchers—including student researchers—are responsible for correctly citing existing sources they use in a study or that inform their work. While it is fine to borrow previously published material (as long as it enhances a unique viewpoint), it must be referenced properly.

To study crime, for example, a researcher might also sort through existing data from the court system, police database, and prison information. It’s important to examine this information in addition to existing research to determine how these resources might be used to fill holes in existing knowledge. Reviewing existing sources educates researchers and helps refine and improve a research study design.

2.4.1.3 Step 3: Formulate a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a testable educated guess about predicted outcomes between two or more variables. In sociology, the hypothesis will often predict how one form of human behavior influences another. For example, a hypothesis might be in the form of an “if, then statement.” Let’s relate this to our topic of crime: If unemployment increases, then the crime rate will increase.

In scientific research, we formulate hypotheses to include an independent variable (IV) , which is the cause of the change, and a dependent variable (DV) , which is the effect , or thing that is changed. In the example above, unemployment is the independent variable and the crime rate is the dependent variable.

In a sociological study, the researcher would establish one form of human behavior as the independent variable and observe the influence it has on a dependent variable. How does gender (the independent variable) affect the rate of income (the dependent variable)? How does one’s religion (the independent variable) affect family size (the dependent variable)? How is social class (the dependent variable) affected by level of education (the independent variable)?

Figure 2.25 Examples of dependent and independent variables. Typically, the independent variable causes the dependent variable to change in some way.

Taking an example from figure 2.25, a researcher might hypothesize that teaching children proper hygiene (the independent variable) will boost their sense of self-esteem (the dependent variable). Note, however, this hypothesis can also work the other way around. A sociologist might predict that increasing a child’s sense of self-esteem (the independent variable) will increase or improve habits of hygiene (now the dependent variable). Identifying the independent and dependent variables is very important. As the hygiene example shows, simply identifying two related topics or variables is not enough. Their prospective relationship must be part of the hypothesis.

2.4.1.4 Step 4: Select a Research Method and Design a Study

Researchers select a research method that is appropriate to answer their research question in this step. Surveys, experiments, interviews, ethnography, and content analysis are just a few examples that researchers may use. You will learn more about these and other research methods later in this chapter. Typically your research question influences the type of methods that will be used.

2.4.1.5 Step 5: Collect Data

Next the researcher collects data. Depending on the research design (step 4), the researcher will begin the process of collecting information on their research topic. After all the data is gathered, the researcher will be able to systematically organize and analyze the data.

2.4.1.6 Step 6: Analyze the Data

After constructing the research design, sociologists collect, tabulate or categorize, and analyze data to formulate conclusions. If the analysis supports the hypothesis, researchers can discuss what this might mean. If the analysis does not support the hypothesis, researchers may consider repeating the study or think of ways to improve their procedure.

Even when results contradict a sociologist’s prediction of a study’s outcome, the results still contribute to sociological understanding. Sociologists analyze general patterns in response to a study, but they are equally interested in exceptions to patterns. In a study of education, for example, a researcher might predict that high school dropouts have a hard time finding rewarding careers. While many assume that the higher the education, the higher the salary and degree of career happiness, there are certainly exceptions. People with little education have had stunning careers, and people with advanced degrees have had trouble finding work. A sociologist prepares a hypothesis knowing that results may substantiate or contradict it.

2.4.1.7 Step 7: Report Findings

Researchers report their results at conferences and in academic journals. These results are then subjected to the scrutiny of other sociologists in the field. Before the conclusions of a study become widely accepted, the studies are often repeated in the same or different environments. In this way, sociological theories and knowledge develop as the relationships between social phenomena are established in broader contexts and different circumstances.

If you still aren’t quite sure about how sociologists use the scientific method, you might enjoy “ The Scientific Method: Steps, Examples, Tips, and Exercise [YouTube Video] ,” which explores why people smile. It also reminds us that people have been using logic and evidence to explore the world for centuries. The video credits Ibn al-Haytham , an eleventh-century Arab Muslim scholar with pioneering the modern scientific method in his study of light and vision (figure 2.26). If the video makes you curious about the science behind why people smile, you might want to check out this current research related to gender and smiling in this article, “ Women smile more than men, but differences disappear when they are in the same role, Yale researcher finds .”

Figure 2.26 Drawing of Ibn al-Hayatham

You might remember that in Chapter 1 , we talked about human society like a forest. We said that individual trees did not exist in isolation. Instead, they were interdependent. They formed a living community. The video in figure 2.27 describes the science behind this knowledge. Please watch at least the first 10 minutes to see if you can discover all the steps of the scientific method that Canadian female scientist Suzanne Simard used in her revolutionary science.

Figure 2.27 Suzanne Simard: How Trees Talk To Each Other [YouTube Video]

2.4.2 Interpretive Framework

You may have noticed that most of the early recognized sociologists in this chapter were White wealthy men. Often, they looked at economics, poverty, and industrialization as their topics. They were committed to using the scientific method. Although women like Harriet Martineau and Jane Addams examined a wide range of social problems and acted on their research, science, even social science, was considered a domain of men. Even in 2020, women are only less than 30% of the STEM (Science Technology Engineering and Math) workforce in the United States (American Association of University Women 2020).

Feminist scientists challenge this exclusion, and the kinds of science it creates. Feminist scientists argue that women and non-binary people belong everywhere in science.They belong in the laboratories and scientific offices. They belong in deciding what topics to study, so that social problems of gendered violence or maternal health are studied also. They belong as participants in research, so that findings apply to people of all gender identities. They belong in applying the results to doing something about social problems. In other words:

Feminists have detailed the historically gendered participation in the practice of science—the marginalization or exclusion of women from the profession and how their contributions have disappeared when they have participated. Feminists have also noted how the sciences have been slow to study women’s lives, bodies, and experiences. Thus from both the perspectives of the agents—the creators of scientific knowledge—and from the perspectives of the subjects of knowledge—the topics and interests focused on—the sciences often have not served women satisfactorily. (Crasnow 2020)

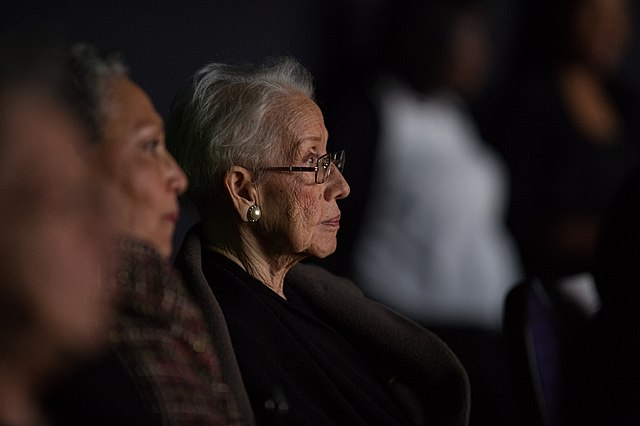

Figure 2.28 NASA “human computer” Katherine Johnson watches the premiere of Hidden Figures after a reception where she was honored along with other members of the segregated West Area Computers division of Langley Research Center.

You may have seen the movie Hidden Figures or read the book. In figure 2.28, Katherine Johnson, an African American mathematician, physicist, and space scientist, watches the premiere of the movie. In it, women, particularly Black women, were the computers for NASA, manually calculating all the math needed to launch and orbit rockets. However, politicians and leaders did not recognize their work. Even when they were creating equations and writing reports, women’s names didn’t go on the title pages.

The practice of science often excludes women and nonbinary people from leadership in research, research topics, and as research subjects. The feminist critque of the traditional scientific method, and other critiques around the process of doing traditional science created space for other frameworks to emerge.

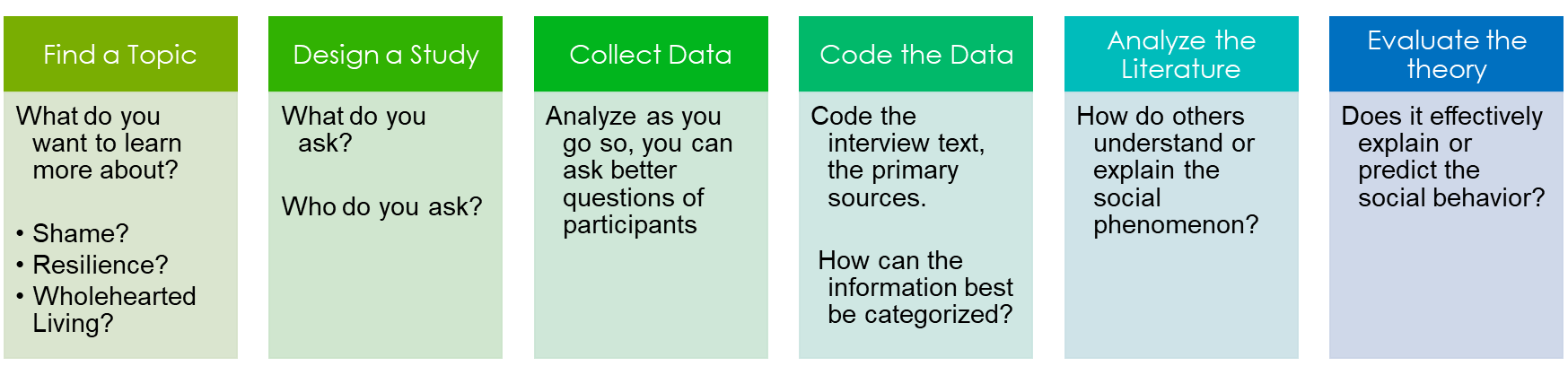

One such framework is the interpretive framework. The interpretive framework is an approach that involves detailed understanding of a particular subject through observation or listening to people’s stories, not through hypothesis testing. Researchers try to understand social experiences from the point of view of the people who are experiencing them. They interview people or look at blogs, newspapers, or videos to discover what people say is happening, and how the people make sense of things. This in-depth understanding allows the researcher to create a new theory about human activity. The steps are similar to the scientific method, but not the same, as you see in figure 2.29.

Figure 2.29. Interpretive framework, Figure 2.29 I mage Description

White American researcher Brene Brown, who you will learn more about in Chapter 3 , describes the approach this way:

In grounded theory we don’t start with a problem or a hypothesis or a literature review, we start with a topic. We let the participants define the problem or their main concern about the topic, we develop a theory, and then we see how and where it fits in the literature. (Brown 2022)

In her own research she interviewed people who she considered resilient to understand how shame works. By listening to resilient people, she was able to develop a theory about how people recover from difficult situations in life. If you are interested in seeing her writing for yourself, check out this blog post on addressing social problems with the power of love: “ Doubling Down on Love .”

Even though both the traditional scientific method and the interpretive framework start with curiosity and questions, the people who practice science using the interpretive framework allow the data to tell its story. Using this method can lead to insightful and transformative results. You can find things you didn’t even know to expect, because you are listening to what the stories say.

2.4.3 Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods

In the video you saw in figure 2.20, Suzanne Simard describes the amazing science she does when she researches how trees talk to each other. The methods she uses, with the possible exception of bringing bear spray, don’t work very well when you study people. Instead social scientists use a variety of methods that allow them to explain and predict the social world. These research methods define how we do social science.

In this section, we examine some of the most common research methods. Research methods are often grouped into two categories: quantitative research , data collected in numerical form that can be counted and analyzed using statistics and qualitative research , non-numerical, descriptive data that is often subjective and based on what is experienced in a natural setting. These methods seem to contradict each other, but some of the strongest scientific studies combine both approaches. New research methods go beyond the two categories, exploring international and Indigenous knowledge, or doing research for the purpose of taking action.

2.4.3.1 Surveys

Do you strongly agree? Agree? Neither agree or disagree? Disagree? Strongly disagree? You’ve probably completed your fair share of surveys, if you’ve heard this before. At some point, most people in the United States respond to some type of survey. The 2020 U.S. Census is an excellent example of a large-scale survey intended to gather sociological data. Since 1790, the United States has conducted a survey consisting of six questions to receive demographic data of the residents who live in the United States.

As a research method, a survey collects data from subjects who respond to a series of questions about behaviors and opinions, often in the form of a questionnaire or an interview. Surveys are one of the most widely used scientific research methods. The standard survey format allows individuals a level of anonymity in which they can express personal ideas.

Not all surveys are considered sociological research. Many surveys people commonly encounter focus on identifying marketing needs and strategies rather than testing a hypothesis or contributing to social science knowledge. Questions such as, “How many hot dogs do you eat in a month?” or “Were the staff helpful?” are not usually designed as scientific research. Surveys gather different types of information from people. While surveys are not great at capturing the ways people really behave in social situations, they are a great method for discovering how people feel, think, and act—or at least how they say they feel, think, and act. Surveys can track preferences for presidential candidates or reported individual behaviors (such as sleeping, driving, or texting habits) or information such as employment status, income, and education levels.

2.4.3.2 Experiments

One way researchers test social theories is by conducting an experiment, meaning the researcher investigates relationships to test a hypothesis. This approach closely resembles the scientific method. There are two main types of experiments: lab-based experiments and natural or field experiments. In a lab setting, the research can be controlled so that data can be recorded in a limited amount of time. In a natural or field-based experiment, the time it takes to gather the data cannot be controlled but the information might be considered more accurate since it was collected without interference or intervention by the researcher. Field-based experiments are often used to evaluate interventions in educational settings and health (Baldassarri and Abascal 2017).

Typically, the sociologist selects a set of people with similar characteristics, such as age, class, race, or education. Those people are divided into two groups. One is the experimental group and the other is the control group. The experimental group is exposed to the independent variable(s) and the control group is not. To test the benefits of tutoring, for example, the sociologist might provide tutoring to the experimental group of students but not to the control group. Then both groups would be tested for differences in performance to see if tutoring had an effect on the experimental group of students. As you can imagine, in a case like this, the researcher would not want to jeopardize the accomplishments of either group of students, so the setting would be somewhat artificial. The test would not be for a grade reflected on their permanent record as a student, for example.

2.4.3.3 Secondary Data Analysis

While sociologists often engage in original research studies, they also contribute knowledge to the discipline through secondary data analysis. Secondary data does not result from firsthand research collected from primary sources. Instead secondary data uses data collected by other researchers or data collected by an agency or organization. Sociologists might study works written by historians, economists, teachers, or early sociologists. They might search through periodicals, newspapers, or magazines, or organizational data from any period in history.

2.4.3.4 Participant Observation

Participant observation refers to a style of research where researchers join people and participate in a group’s routine activities for the purpose of observing them within that context. This method lets researchers experience a specific aspect of social life. A researcher might go to great lengths to get a firsthand look into a trend, institution, or behavior. For instance, a researcher might work as a waitress in a diner, experience homelessness for several weeks, or ride along with police officers as they patrol their regular beat. Often, these researchers try to blend in seamlessly with the population they study, and they may not disclose their true identity or purpose if they feel it would compromise the results of their research.

At the beginning of a field study, researchers might have a question: “What really goes on in the kitchen of the most popular diner on campus?” or “What is it like to be homeless?” Participant observation is a useful method if the researcher wants to explore a certain environment from the inside. The ethnographer will be alert and open minded to whatever happens, recording all observations accurately. Soon, as patterns emerge, questions will become more specific, and the researcher will be able either make connections to existing theories or develop new theories based on their observations. This approach will guide the researcher in analyzing data and generating results.

2.4.3.5 In-depth interviews

Interviews, sometimes referred to as in-depth interviews, are one-on-one conversations with participants designed to gather information about a particular topic. Interviews can take a long time to complete, but they can produce very rich data. In fact, in an interview, a respondent might say something that the researcher had not previously considered, which can help focus the research project. Researchers have to be careful not to use leading questions. You want to avoid leading the respondent into certain kinds of answers by asking questions like, “You really like eating vegetables, don’t you?” Instead researchers should allow the respondent to answer freely by asking questions like, “How do you feel about eating vegetables?”

2.4.4 International Research

International research is conducted outside of the researcher’s own immediate geography and society. This work carries additional challenges considering that researchers often work in regions and cultures different from their own. Researchers need to make special considerations in order to counter their own biases, navigate linguistic challenges and ensure the best cross cultural understanding possible. This webpage shows a map and descriptions of field projects around the world by students at Oxford University’s Masters in Development Studies. What are some interesting projects that stand out to you?

For example, in 2021 Jörg Friedrichs at Oxford published his research on Muslim hate crimes in areas of North England where Islam is the majority religion. He studied police data of racial and religious hate crimes in two districts to look for patterns related to the crimes. He related those patterns to the wider context of community relations between Muslims and other groups, and presented his research to hate crime practitioners in police, local government and civil society (Friedrichs 2021).

2.4.5 Indigenous Knowledge

Indigenous scientists also critique traditional ways of doing science. Often, Western science will break things down into parts to understand what each part does. While that may help understand details, it doesn’t give the whole picture of a process or help understand the interdependence in the social and physical world. Also, Western science values intellectual ways of knowing. Intuition, empathy, and connection are not valued. Robin Wall Kimmer, an Indigenous biologist from the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, writes this:

Native scholar Greg Cajete has written that in indigenous ways of knowing, we understand a thing only when we understand it with all four aspects of our being: mind, body, emotion, and spirit. I came to understand quite sharply when I began my training as a scientist that science privileges only one, possibly two, of those ways of knowing: mind and body. As a young person wanting to know everything about plants, I did not question this. But it is a whole human being who finds the beautiful path. (Kimmerer 2013)

When we can do science using all of our ways of knowing, our answers become richer. As the world becomes more aware of increases in the environmental crisis, researchers are more often acknowledging the ways that Indigenous peoples care for their ecological surroundings. As Indigenous communities conduct their own fieldwork to identify and document their own knowledge they are able to engage with research as agents of ecological conservation.

Figure 2.30 Consider This with Robin Wall Kimmerer [YouTube Video]

In the video in Figure 2.30, Kimmerer has a longer conversation about what it means to be American. Starting around minute 55:25 she shares the importance of naming, and how naming can sometimes shut down learning. Please listen to her words for yourself, and reflect on how the practices she introduces might change your own approach to science.

2.4.6 Community-Based Research and Participatory Action Research

Social problems sociologists and other social scientists often conduct their research so that they can take action. Action research is a family of research methodologies that pursue action (or change) and research (or understanding) at the same time. We see this when the government changes a policy based on data or when a community organization tries a new evidence-based approach for providing services. One of the most visible applications of social problems research is through humanitarian or social action efforts.

2.4.6.1 Humanitarian Efforts

One effective example of social action efforts is in the work of Paul Farmer. Farmer was a public health physician, anthropologist, and founder of partners in health. Until his death in 2022, he focused on epidemiological crises in low and middle income countries.

One trend that Farmer championed was the importance of good health and health care as human rights. He contributed to a broader understanding that poor health is a symptom of poverty, violence and inequality (Partners in Health 2009). If you want to learn more, please watch the NPR video essay, “ Paul Farmer: I believe in health care as a human right ” [YouTube Video] where he describes this view. What field experiences of Farmer’s do you see allowed him to develop this view?

Farmer applied this human rights perspective to pandemics. His book, Fevers, Feuds and Diamonds: Ebola and the Ravages of History , looks at the 2014 Ebola crisis, and what we can learn from it to apply to the COVID-19 epidemic. In a PBS Newshour interview he spoke of his work during the Ebola outbreak:

>Early in the Ebola outbreak, almost all of our attention was turned towards clinical services. But we kept on bumping into things we didn’t understand and sometimes even our colleagues from Sierra Leone and Liberia didn’t understand. And that just triggered an interest in a deeper understanding of the place, the culture, the history. (Public Broadcasting Service 2021).

Farmer shares his experiences both as a medical doctor and a researcher, asking the questions: “Who is most impacted by disease? How might things have been done differently? What can be done now?” His research on Ebola focused on circumstances in West Africa where lack of medical resources and decades of war played a role in the epidemic, and how the epidemic itself, as we experience in the United States with Covid, revealed underlying problems and inequities in society (Public Broadcasting Service 2021). We’ll explore topics of health, inequality and interdependence more deeply in Chapter 7 .

2.4.6.2 Community-Based Action Research

Community-based research takes place in community settings. It involves community members in the design and implementation of research projects. It demonstrates respect for the contributions of success that are made by community partners. Research projects involve collaboration between researchers and community partners, whether the community partners are formally structured community-based organizations or informal groups of individual community members. The aim of this type of research is to benefit the community by achieving social justice through social action and change.

2.4.6.3 Participatory Action Research

Community-based research is sometimes called participatory action research (Stringer 2021). In partnership with community organizations, researchers apply their social science research skills to help assess needs, outcomes, and provide data that can be used to improve living conditions. The research is rigorous and often published in professional reports and presented to the board of directors for the organization you are working with. As it sounds, action research suggests that we make a plan to implement changes. Often with academic research, we aim to learn more about a population and leave the next steps up to others. This is an important part of the puzzle, as we need to start with knowledge but action research often has the goal of fixing something or at least quickly translating the newly acquired findings into a solution for a social problem.

To learn more about participatory action research, check out this short 4 minute clip for an introduction with Shirah Hassan of Just Practice (figure 2.31):

Figure 2.31 Participatory Action Research with Shirah Hassan [YouTube Video]

Community-based action research looks for evidence. As new insights emerge, the researchers adjust the question or the approach. This type of research engages people who have traditionally been referred to as subjects as active participants in the research process. The researcher is working with the organization during the whole process and will likely bring in different project design elements based on the needs of the organization. Social scientists can bring more formalized training, but they draw both on existing research/literature and goals of the organization they are working with. Community-based research or participatory research can be thought of as an orientation for research rather than strictly a method. Often a number of different methods are used to collect data. Change can often be one of the main aims of the project, as we will see in the box below.

2.4.7 Research Ethics

How we do science and how we apply our results is more challenging than it might first appear. The American Sociological Association (ASA) is the major professional organization of sociologists in North America. ASA is a great resource for students of sociology as well. The ASA maintains a code of ethics —formal guidelines for conducting sociological research—consisting of principles and ethical standards to be used in the discipline. These formal guidelines were established by practitioners in 1905 at John Hopkins University, and revised in 1997. When working with human subjects, these codes of ethics require researchers’ to do the following:

- Maintain objectivity and integrity in research

- Respect subjects’ rights to privacy and dignity

- Protect subject from personal harm

- Preserve confidentiality

- Seek informed consent

- Acknowledge collaboration and assistance

- Disclose sources of financial support

2.4.8 Unethical Studies

Unfortunately, when these codes of ethics are ignored, it creates an unethical environment for humans being involved in a sociological study. Throughout history, there have been numerous unethical studies, as we’ll explore in the following sections.

2.4.8.1 The Tuskegee Experiment

This study was conducted 1932 in Macon County, Alabama, and included 600 African American men, including 399 diagnosed with syphilis. The participants were told they were diagnosed with a disease of “bad blood.” Penicillin was distributed in the 1940s as the cure for the disease, but unfortunately, the African American men were not given the treatment because the objective of the study was to see “how untreated syphilis would affect the African American male” (Caplan 2007). This study was shut down in 1972, because a reporter wrote that at least 128 people had died from syphillis or related complications (Nix 2020).

2.4.8.2 Milgram Experiment

In 1961, psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted an experiment at Yale University. Its purpose was to measure the willingness of study subjects to obey an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts that conflicted with their personal conscience. People in the role of teacher believed they were administering electric shocks to students who gave incorrect answers to word-pair questions. No matter how concerned they were about administering the progressively more intense shocks, the teachers were told to keep going. The ethical concerns involve the extreme emotional distress faced by the teachers, who believed they were hurting other people. (Vogel 2014). Today this experiment would not be allowed because it would violate the ethical principal of protecting subjects from personal harm.

2.4.8.3 Philip Zimbardo and the Stanford prison experiment

In 1971, psychologist Phillip Zimbardo conducted a study involving students from Stanford University. The students were put in the roles of prisoners and guards, and were required to play their assigned role accordingly. The experiment was intended to last two weeks, but it only lasted six days due to the negative outcome and treatment of the “prisoners.” Beyond the ethical concerns, the study’s validity has been questioned after participants revealed they had been coached to behave in specific ways. Today, this experiment would not be allowed because it would violate a participants right to dignity, and protection from harm.

2.4.8.4 Laud Humphreys

In the 1960s, Laud Humphreys conducted an experiment at a restroom in a park known for same-sex sexual encounters. His objective was to understand the diversity of backgrounds and motivations of people seeking same-sex relationships. His ethics were questioned because he misrepresented his identity and intent while observing and questioning the men he interviewed (Nardi 1995). Today this experiment would not be allowed because participants did not provide informed consent, among other issues.

2.4.9 Licenses and Attributions for Research Methods for Social Problems

2.4 Research methods for social problems.

Puentes and Gougherty https://docs.google.com/document/d/1BOCrIQ5xDJD1RbVdmS1glMeaKurj4fHgF5hkn2P77-U/edit#heading=h.lc1f68rgruem Slightly summarized

Figure 2.23 – Ways of Knowing and Examples by Kimberly Puttman. License: CC-BY-ND

Figure 2.24 The Scientific Method as an Ongoing Process by Michaela Willi Hooper and Jennifer Puentes. License: CC-BY-4.0.

Figure 2.25 Examples of dependent and independent variables. Typically, the independent variable causes the dependent variable to change in some way. [c] [d]

Figure 2.26 Drawing of Ibn al-Hayatham by Unknown Artist, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons public domain.

Figure 2.27 “ How Trees Talk To Each Other ” by Suzanne Simard. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

2.4.2 Interpretive Frameworks by Kimberly Puttman. License: CC-BY-4.0

Figure 2.28 “ Hidden Figures Premiere ” by NASA/Aubrey Gemignani, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons public domain.

Figure 2.29. Interpretive Framework Source – Kim Puttman [e]

Figure 2.30 “ Consider This with Robin Wall Kimmerer ” by Oregon Humanities . License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Figure 2.31 “ Participatory Action Research ” with Shirah Haasan by Vera Instit ute of Justice . License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Social Problems Copyright © by Kim Puttman. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- Member Login

- Social Justice and Activism

- Anti-Harassment Policy

- 2024-2025 Roster of Officers and Committee Members

- Past Presidents, Vice-Presidents, and Editors

- Member Testimonials

- I. The Executive Officer, Administrative Office, and The Board of Directors

- II. The Volunteer Officers

- III. The Divisions

- IV. The Committees

- Social_Problems /">V. The Editorial Office of Social Problems

- VI. The Editors of the Agenda for Social Justice

- VII. General Guidelines on Contracts & Biddable Work

- VIII. The SSSP Schedules & Cycles

- Budget, Minutes, Reports, and Survey Results

- Membership Benefits

- Donate to SSSP

- Join/Renew SSSP

- Purchase Gift Membership

- Redeem Gift Membership

- General Elections

- Division Elections

- Resolution Elections

- Statement Elections

- Proposed By-Laws Amendments Elections

- Proposed Membership Dues Increase Elections

- Job Opportunities

- Call for Chapters, Papers, Proposals, Conferences, and Events

- Fellowships & Scholarships

- Mentoring Program

- Virtual Events

- Members Directory

- SSSP Listserv

- Members News

- Student Member Spotlight

- Membership List Rental

- About SSSP Annual Meetings

- Featured Abstracts

- 2025 Call For Papers

- For Session Organizers

- Annual Meeting FAQ

- Annual Meeting Information

- Author Meets Critics Sessions – Call for Books Opportunity

- 2024 Annual Meeting

- 2023 Annual Meeting

- Future Annual Meetings

- Past Annual Meetings

- Current Editors

- Editorial Board

- The Authors' Attic

- Subscriptions

- Online Access

- Instructions to Authors

- Correspondence

- Oxford University Press

- Rights and Permissions

- Impact Factor and Ranking

- Agenda for Social Justice

- Global Agenda for Social Justice

- Social Problems in the Age of COVID-19 Volume 1

- Social Problems in the Age of COVID-19 Volume 2

- Arlene Kaplan Daniels Paper Award

- C. Wright Mills Award

- Doris Wilkinson Faculty Leadership Award

- Joseph B. Gittler Award

- Kathleen S. Lowney Mentoring Award

- Lee Founders Award

- Student Paper Competitions and Outstanding Scholarship Awards

- Thomas C. Hood Social Action Award

- Travel Fund Awards

- Racial/Ethnic Minority Graduate Fellowship

- Beth B. Hess Memorial Scholarship

- Past Winners

- Roles and Responsibilities of Division Chairs

We are an interdisciplinary community of scholars, practitioners, advocates, and students interested in the application of critical, scientific, and humanistic perspectives to the study of vital social problems.

Learn more.

SSSP Anti-Harassment Policy

If you are a member of the SSSP, or considering membership, please read this policy carefully. We want to assure members that we will do what we can to provide them with a safe environment in which they will be free to pursue their intellectual interests and engage other members in spirited, stimulating, and productive intellectual exchanges.

View the SSSP Statement and Policy against Discrimination and Harassment . Make an anonymous report regarding behavior that violates the anti-harassment policy.

SSSP Anti-Harassment Advocates

These SSSP members have participated in discussions of our policy, advocacy principles, and our commitment to a welcoming culture, and they are available to consult with members seeking related information, resources and support.

Action and Activism

Sssp statement on campus protests (4/30/24).

The Society for the Study of Social Problems (SSSP) condemns the actions taken by police agents and university leaders in response to pro-Palestinian campus protests around the country. We unequivocally support academic freedom, free speech, and the right to peaceful protest.

Click here for more Action items...

2024 SSSP Approved Resolutions

SSSP resolutions constitute an important opportunity for our scholar-activist membership to analyze and offer their opinions on contemporary social problems that we believe the Society should address as a social justice organization. All SSSP members were invited to review the proposed 2024 resolutions and participate in the resolutions process.

Click here to view the 2024 Approved Resolutions.

2024 SSSP Approved Statements

Thank you to those who voted on the SSSP Statements – January 2024. 277 votes were cast; 21% of the membership participated in the election. Proposed Statement 2 and the General Item: "SSSP should issue a statement on the violence happening in Palestine and Israel" passed, but Proposed Statement 1 did not pass.

Click here to view the 2024 Approved Statement.

What Our Members Say

I’m excited about a new generation of members who are bringing creativity, scholarly excellence and visons of emancipatory change to SSSP. They are a key pillar of what will fuel the Society forward in the years to come. I know we need the deepest of commitments, the sharpest scholarship, and the greatest strategic clarity regarding the road ahead. I’m very much looking forward to the annual meeting in Chicago where much of this theory and practice will be shared as we commemorate the 75th anniversary of SSSP."

Rose M. Brewer, SSSP President 2024-2025, University of Minnesota

Read more member experiences with SSSP.

journalLink

- Social Problems Journal Main Page

- Annual Meetings

Latest SSSP News

Sssp j21 committee position available – editorial team (application deadline: 12/1/24), together we can make a difference, proposed 2025 membership dues increase election open for voting, the 2025 call for papers is now available, call for proposals: global agenda for social justice 3.

- Privacy Policy

- Website Programming

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- The Authors' Attic: Interviews with Authors

- High Impact Articles

- Award-Winning Articles

- Virtual Issues

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Why Submit?

- About Social Problems

- About the Society for the Study of Social Problems

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact SSSP

- Contact Social Problems

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

High-Impact Articles

Social Problems , the official publication of the Society for the Study of Social Problems (SSSP) , is a quarterly journal that covers an extensive array of complex social concerns from race and gender to labor relations to environmental issues and human rights; it has been an important forum for sociological thought for over six decades.

OUP has granted free access to the articles on this page that represent a selection of the most cited, most read, and most discussed articles from 2019 and 2020. These articles are just a sample of the impressive body of research from Social Problems .

Most Discussed

- X (formerly Twitter)

- Recommend to Your Librarian

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1533-8533

- Print ISSN 0037-7791

- Copyright © 2024 Society for the Study of Social Problems

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Social Problems is the official publication of The Society for the Study of Social Problems and has been has been an important forum for sociological thought for over six decades. Access a selection of notable articles from Social Problems that offer a sample of the impressive body of research from the journal.

Published quarterly for the Society for the Study of Social Problems, Social Problems tackles the most difficult of contemporary society's issues and brings to the fore influential sociological findings and theories enabling readers to gain a better understanding of the complex social environment.

The major types of research on social problems include surveys, experiments, observational studies, and the use of existing data. Surveys are the most common method, and the results of surveys of random samples may be generalized to the populations from which the samples come.

2.4 Research Methods for Social Problems Theories discuss the why of particular social problems. They begin to systematically explain, for example, why socioeconomic class is prevalent in industrialized societies, or why implicit bias is so common.

We are an interdisciplinary community of scholars, practitioners, advocates, and students interested in the application of critical, scientific, and humanistic perspectives to the study of vital social problems.

Social Problems, Volume 71, Issue 4, November 2024, Pages 1048–1067, https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spac052

Social Problems, the official publication of the Society for the Study of Social Problems (SSSP), is a quarterly journal that covers an extensive array of complex social concerns from race and gender to labor relations to environmental issues and human rights; it has been an important forum for sociological thought for over six decades.

These recent institutional efforts to focus social science attention on the solving of major social problems raise the question of whether social science research provides usable guidance about how to reduce inequality.

The sociological study of social problems is reviewed in terms of the question of conceptualizing the key term social problems as a technical term in the discipline and beyond. Dilemmas brought by the very word problem , by who uses it and how, are considered.

Recent studies published in management journals have expanded a traditional focus on organizational problems by a new focus on social problems such as sex trafficking (Ruebottom & Toubiana, 2021), child marriage (Claus & Tracey, 2021) or homelessness (Lawrence & Dover, 2015).